Beautiful Wahclella Falls in the massive rock cathedral that Tanner Creek has sculpted

Fifty years once seemed like a very long time to me – half a century! Fifty years before I showed up on this planet (in 1962) human flight had barely been mastered and automobiles had just begun to replace the horse and buggy. Looking back today upon the past fifty years, things seems less changed from the perspective of a 61-year-old (though it’s true that without the arrival of personal computers and the internet, I wouldn’t be posting this article!) Our sense of passing time is warped by our own very short lives.

That’s the gift of witnessing the natural world around us moving forward at its own pace, as it has for millennia. Fifty years is a fleeting moment in time to our mountains and forests, where the only constant is change and the seemingly endless repetitions in the of cycle life that plays out on the landscape. Seeing these larger systems at work is a reassuring escape from our daily lives driven by deadlines and chores, and a reminder of the larger natural order that we belong to.

Tanner Creek weaving through the mossy boulder gardens below Wahclella Falls

This article is a 50-year snapshot of a catastrophic landslide in the Columbia River Gorge that perfectly illustrates these forces at work, right before our eyes. The landslide took place in the lower gorge of the Tanner Creek canyon in 1973, triggering a cascade of events that are still playing out today. It might have gone unnoticed at the time by all but a few avid hikers had there not been an earlier human presence at Tanner Creek dating back to very start of the 20thcentury.

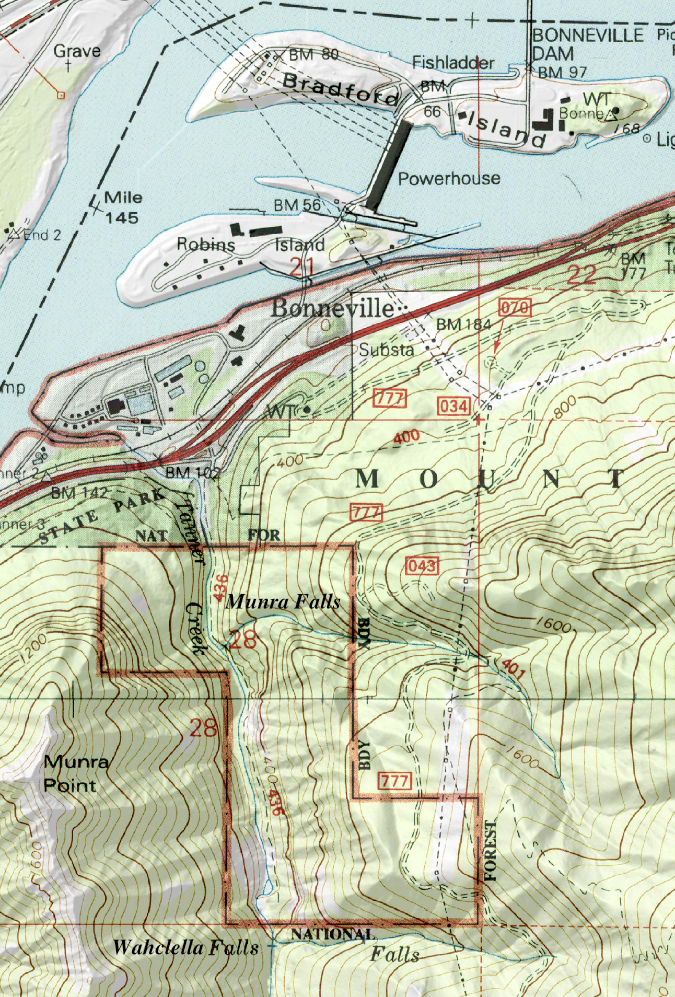

The story begins at the Bonneville Fish Hatchery, located at the mouth of Tanner Creek. Built in 1909, it remains as one of the oldest hatcheries in the State of Oregon’s system, and was established as a place to breed salmon fry to be shipped to other hatcheries around the state. The map below shows the proximity of Tanner Creek to the Columbia River, Bonneville Dam and today’s Interstate 84.

The Tanner Creek gorge is located on the south side of the Columbia River at Bonneville, in the heart of the Gorge

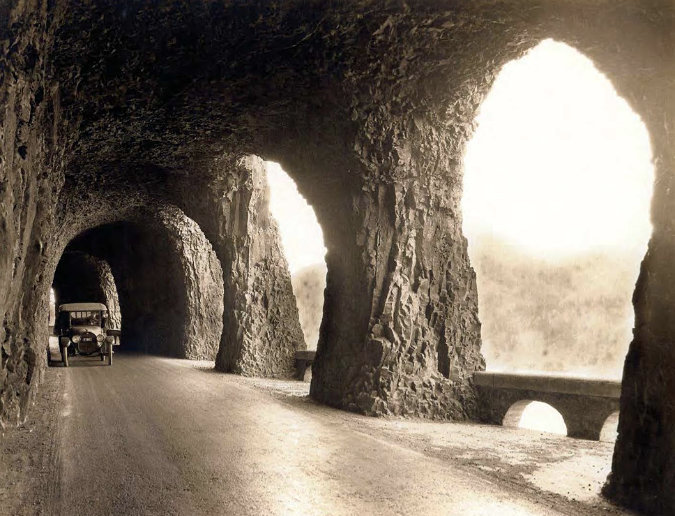

The Bonneville Hatchery opened five years before the Historic Columbia River Highway arrived at Bonneville, when Gorge travel was still by train or boat. It was completed nearly 30 years before Bonneville Dam was constructed, though expanded as part of the dam construction project. Over its nearly 125 years of operation, The Bonneville Hatchery has been expanded and upgraded several times in an attempt to keep pace with continued dam building upstream on the Columbia River. The hatchery continues to be a popular tourist attraction, with stocked ponds and interpretive displays.

Construction of the hatchery diversion dame on Tanner Creek in about 1907 – note two men standing on the pipeline intake structure (OSU Archives)

The hatchery diversion dam today

The Bonneville Fish Hatchery originally depended on the cold, clear mountain water of Tanner Creek for its existence. When the hatchery was constructed in 1908, a small diversion dam was built one-half mile upstream from the main hatchery and a supply pipeline was built along the west bank of Tanner Creek to carry stream water to the hatchery ponds. The original diversion dam still exists today, though most of the hatchery water now comes from wells. The old pipeline has since been replaced, and is now buried under the short access road that hikers follow to the old dam and the start of the Wahclella Falls trail.

The original pipeline that carried Tanner Creek water to the Bonneville Fish Hatchery nearing completion in about 1908

Today’s access road to the diversion dam replaces the old water supply pipeline, and doubles as the first half mile of the Wahclella Falls Trail. This view is in roughly the same spot as the previous historic photo

When the Tanner Creek landslide occurred in 1973, it was first noticed by hatchery workers after the water supply suddenly stopped flowing. An investigation upstream revealed a massive cliff collapse along the west all of the canyon, just below Wahclella Falls. The resulting landslide had completed blocked Tanner Creek, temporarily blocking the streamflow below the landslide.

There was a rough user trail to Wahclella Falls in the days of the landslide, but it was a sketchy affair, crossing several treacherous, small landslide chutes on the east side of the canyon. Hikers parked at a gravel turnaround by the access road gate (located at today’s Wahclella Falls parking area) to reach the trail. By the late 1980s, the modern trail we know today was conceived, with much of it built by volunteers. When the new loop trail was completed in the early 1990s, the landslide was deemed stable enough to be traversed by the new trail. This has allowed countless hikers over the past 30 years to see the spectacle close-up.

Hikers are dwarfed by the Tanner Creek landslide debris – especially the house-sized boulder in the middle of the debris field

Loose material from a landslide typically forms a steep, cone-shaped pile at its terminus, known as a debris fan. Today, the landslide debris fan from the 1973 landslide appears as a green, moss and fern-covered talus slope with a few young trees gradually becoming established in the rubble. A few truck and house-sized boulders poke through the surface of the smaller talus. Below the talus slope, Tanner Creek has stripped away much of the small debris, exposing several of these giant basalt boulders in a dramatic rock garden that the stream continues to shape and shift.

What caused the landslide?

Three epic geologic events continue dominate how the Gorge is shaped today, including the 1973 landslide at Tanner Creek and the many smaller cliff collapses and landslides that occur every year. The first event created the underlying geology of the Gorge, and dates back about 17 million years. On the Oregon side of the river, ancient layers of volcanic ash and debris (similar to what Mount St. Helens produced in the 1980 eruption) accumulated to form the loosely consolidated geologic foundation, and is visible at river level. This unstable base is known as the Eagle Creek Formation.

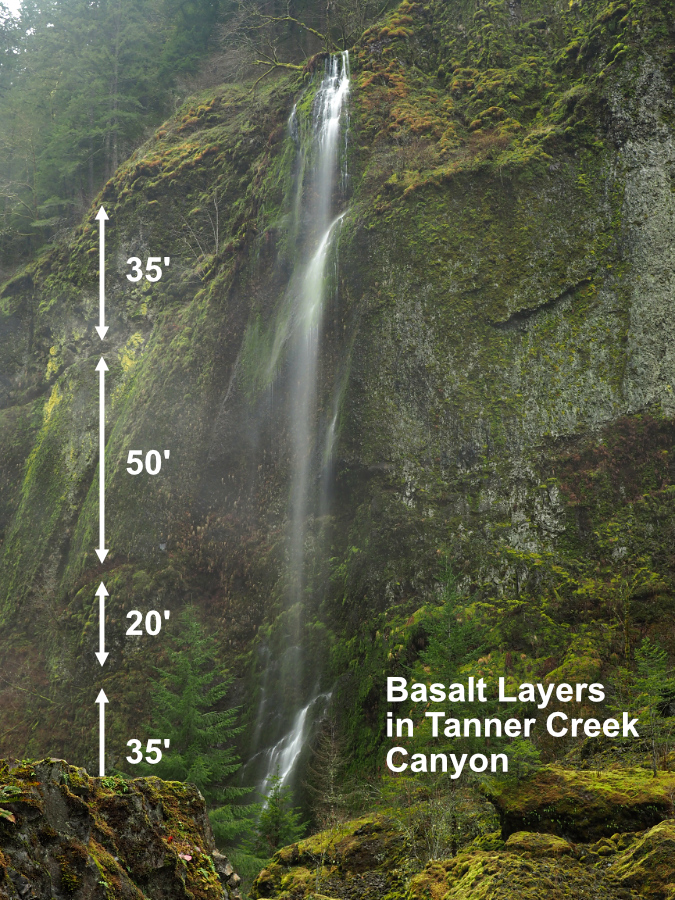

The second event occurred between 12 and 16 million years ago, when hundreds of epic lava flows originating near today’s Steens Mountain flooded much of Oregon, leaving behind thousands of feet of “flood basalts” in stacked layers. These are collectively known as the Grande Ronde Formation and make up the layers we can plainly see in the towering cliffs that make dominate the Gorge landscape today. For this article, they will simply be referred to as Columbia River Basalt.

Thick layers of ancient Columbia River Basalt make up the steep walls of Tanner Creek canyon and much of the surrounding Gorge landscape. Individual basalt layers can range from a few feet to 50 feet or more in depth

The underlying ash and debris layers of the Eagle Creek Formation are less obvious than the overlying basalt, but this formation is familiar to hikers. Named for Eagle Creek in the Gorge, hikers slip and slide during the wet months on the muddy trail surface where the first mile or so of the famous Eagle Creek Trail is built across this material.

Compared to the hard, black layers of basalt that form the bulk of the overlying geology, the Eagle Creek formation is very unstable, especially when exposed to weathering or stream erosion. And though the overlying layers of basalt are comparatively hard and durable, their weakness comes from the extensive fractures that form when basalt lava flows cool, creating the familiar columns that are common throughout the Gorge (more about that weakness in a moment).

Loosely consolidated volcanic avalanche debris known as the Eagle Creek Formation underlies thousands of feet of basalt layers in the Gorge, making for an unstable, easily eroded foundation

Eagle Creek Formation makes up this wall along the lower section of the Tanner Creek Trail

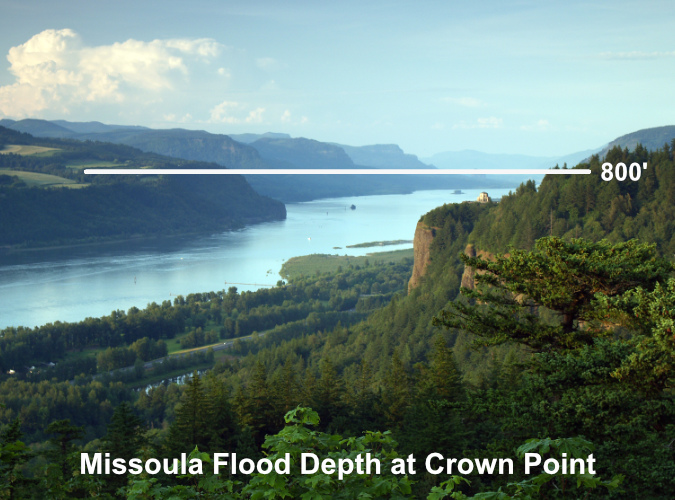

The third epic event came long after the volcanic ash and lava had cooled and at the end of last ice age. During a period from about 13,000 to 15,000 years ago, a series of catastrophic floods from collapsing glacial lakes in today’s western Montana and northern Idaho and Washington rushed across the landscape of the Columbia Basin, then pushed through the Columbia River Gorge toward the Pacific Ocean. Compared to the volcanic episodes that created the Eagle Creek Formation and Columbia River Basalts, the glacial floods occurred yesterday, by geologic standards, and their impact is still playing out today.

The floodwaters were an astonishing 800 to 1000 feet deep as they rushed through the Gorge, carving the steep, dramatic gorge we know today. These are now known as the Bretz Floods, and scientist now believe there were over 40 separate flood events over the course of this period. The floods named for Harlen Bretz, a brilliant, visionary geologist who bravely persevered against intense criticism of his theory behind these events before they were finally accepted by the scientific community in the 1960s and 70s.

The trademark waterfalls of the Gorge are a product of the Bretz Floods where the stacked layers of ancient flood basalts were stripped of loose slopes and debris, revealing the soaring, vertical cliffs and dramatic waterfalls we see today. Where these waterfalls occurred on larger, more powerful streams like Tanner Creek, time and constant erosion has gradually migrated them upstream and away from the Columbia River over the millennia.

The succession of massive ice age floods known as the Bretz Floods easily topped Crown Point, stripping away all but the basalt cliffs, just as the floods shaped the sheer cliffs we see throughout the Gorge today

Since the great floods, Tanner Creek has persistently swept away debris from each successive landslide and cliff collapse, continually eroding the heavy basalt layers from below and setting the stage for the next landslide event. The underlying Eagle Creek formation speeds up this process because it lies at river level in the Gorge, allowing both the Columbia River and its tributary streams to actively undercut the towering basalt walls that rest upon this unstable, underlying layer.

Today, Wahclella Falls marks the current spot where Tanner Creek continues to carve its own, ever-longer gorge, now more than a mile long from where it began after the floods. Seen in this timeframe, the 1973 landslide at Tanner Creek was just one event in hundreds of similar cliff collapses and landslides over time that continue to shape the Gorge we know today.

Weathered basalt often spalls according to the cooling cracks that formed when the lava flows cooled, creating the familiar stone columns common in the Gorge.

The cooling cracks in the basalt layers help, too, as they allow slabs of basalt to continually calve off where the cliffs have been undercut by erosion (see the photo, above). The cracks that form the columns in basalt also allow water to seep in when exposed to weather, and when the water freezes it expands, eventually splitting the rock. While most basalt columns are 5-sided, they may have anywhere from 3-7 sides or be less organized in their cooling patterns. As the example above shows, the columns typically break into pieces on impact when they fall, turning them into the smaller blocks of sharp-cornered basalt. When these blocks make it into a large stream like Tanner Creek, they are further tumbled and broken down into smaller pieces and moved downstream.

Whole chunks of basalt also split off when fractures in the rock are expanded by repeated freezing and thawing of water that seeps into the cracks. The raw, dark area at the center in this view just downstream from Wahclella Falls mark the spot where the boulders at the base of the cliff split off a few years ago. Moss will soon cover the evidence of this collapse.

The spalling process is underway on every sheer basalt face in the Gorge, and most of the steep talus slopes in the Gorge were created this way, gradually growing over time as new basalt chunks drop onto the rock slope from spalling cliffs above. This phenomenon occurs at scales both small and large throughout the Gorge, from individual columns spalling off to entire rock slabs and cliff faces that also break up into smaller pieces on impact. It was basalt wall collapse like this that triggered the 1973 Tanner Creek landslide.

The monumental crash nobody heard…

The sole known account of the 1973 landslide at Tanner Creek comes from Don and Roberta Lowe, legendary hiking guide pioneers in Oregon. Their first guide to trails in the Columbia River Gorge was published in 1980, and included this description of the event:

_________________

“In 1973, attendants at the Bonneville Dam Fish Hatchery were surprised, puzzled and alarmed when the water supply to the facility by Tanner Creek abruptly stopped. When the flow did not resume after a short time, the men became worried, as hatcheries require constant supply of fresh water, so they hiked up Tanner Creek to learn what had happened.

“The canyon was filled with an eerie calm and almost unearthly ambience. A short distance before Wahclella Falls, they found the answer: several hundred cubic yards of the west wall had fallen away and blocked the stream, forming a small lake behind the dam. Fortunately, water began flowing through the debris before any damage was done in the hatchery. The lake (although not as large as it was soon after the landslide) and the slide area still can be seen from the trail – an intimidating view.”

-From “35 Hiking Trails: Columbia River Gorge” by Don and Roberta Lowe (1980)

_________________

The Lowe guide goes on to describe the very rustic trail to Wahclella Falls as it existed in the 1970s, a slippery boot path the Lowes describe as “tricky” during the wet season, including a rock-hop along Tanner Creek near the trailhead – a far cry from today’s well-graded, family friendly trail.

It’s hard to imagine what the scene must have been like when the basalt cliffs gave way along Tanner Creek in 1973, but it must have been extraordinarily loud! Dozens of massive, house-sized boulders managed to roll all the way to Tanner Creek, several hundred feet below, part of a huge debris fan that measures more than a quarter mile across. What we can’t know is whether it happened as a single event, or series of collapses over hours, or even days, though the complete damming of Tanner Creek – a sizable stream with a powerful flow — suggests a single, catastrophic event.

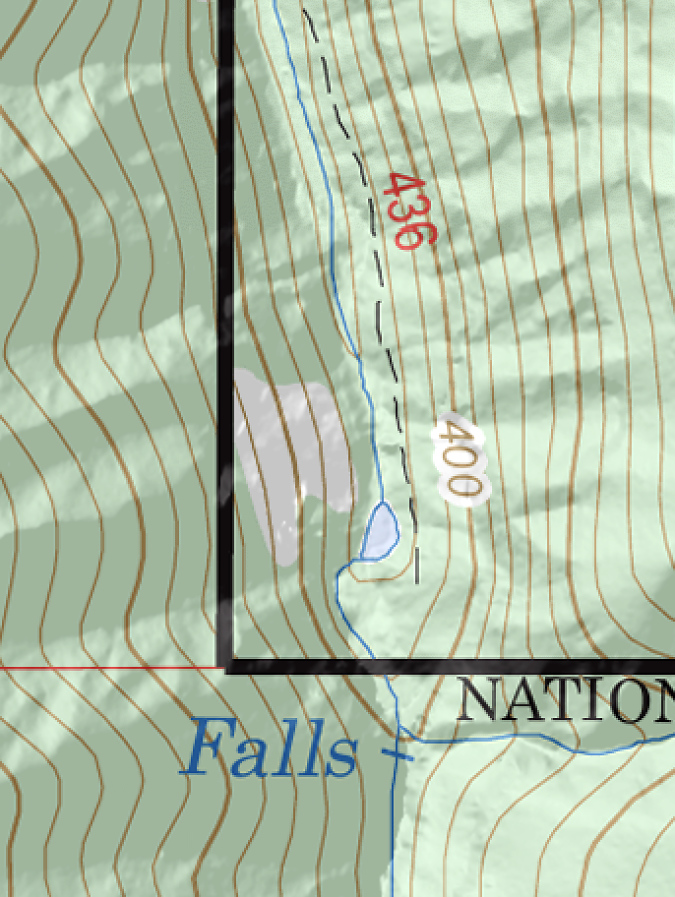

The temporary lake behind the landslide debris lasted long enough to make it onto U.S. Geological Survey maps that were being updated in the 1970s. The bare slopes of the debris fan were also shown on the new maps. Part of the lake persisted well into the 1980s, when I made my first trip into the canyon. Photos from the trip that I have included in this article show just how raw the landslide area continued to be more than a decade after the collapse.

The tiny, temporary lake resulting from the landslide was timed perfectly to be included on USGS maps. Tanner Creek has since carved through the landslide debris and the lake is no longer

The tiny lake on Tanner Creek persisted into the 1980s – this view is from 1986

In preparing this article, I searched for official accounts of the landslide event and historic photos of the west wall of the canyon from before the landslide, but found neither. Therefore, the following schematics are based upon visual evidence on the surviving cliff face above the landslide and the sheer amount of debris that came down. It must have been involved a very large section of the canyon wall. Another guide for these schematics was the recent pair of cliff collapses at nearby Eagle Creek (described in this article), where the “before” conditions were well-documented could be easily compared with the amount to debris produced in these similar, though somewhat smaller events.

Visualizing the landslide aftermath

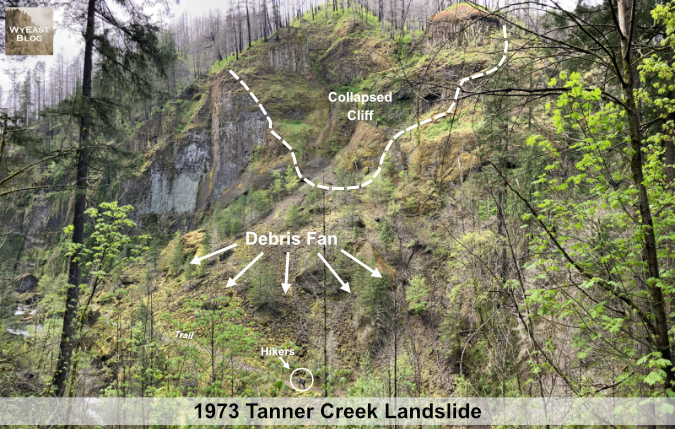

The first schematic view of the landslide is from high on the east slope of Tanner Creek Canyon, where the modern trail approaches a footbridge over a tributary stream (below). Wahclella Falls is just out of view to the left, and Tanner Creek can be seen in the lower left of this view. The dark cliffs on the left side of the photo were not involved in the collapse, so they provide a reasonable sense of what the west wall must have looked like before the 1973 collapse and landslide.

[click here to open a large version in a new tab]

The dashed line shows the extent of the collapse, where the canyon wall gave way. Large, intact slabs of basalt that were once part of the wall poke through the loose debris of the fan, below. This is common when basalt cliffs collapse, as the amount of fracturing within the layers of rock determines whether the individual layers hold together in large chunks as they fall, or complete disintegrate into the loose talus rock that makes up most of the Tanner Creek debris fan. The arrows show the direction in which rock from the collapse tumbled, creating the debris fan we see today. The circled hiker on the lower leg of the loop trail provides a sense of scale against the massive slide area.

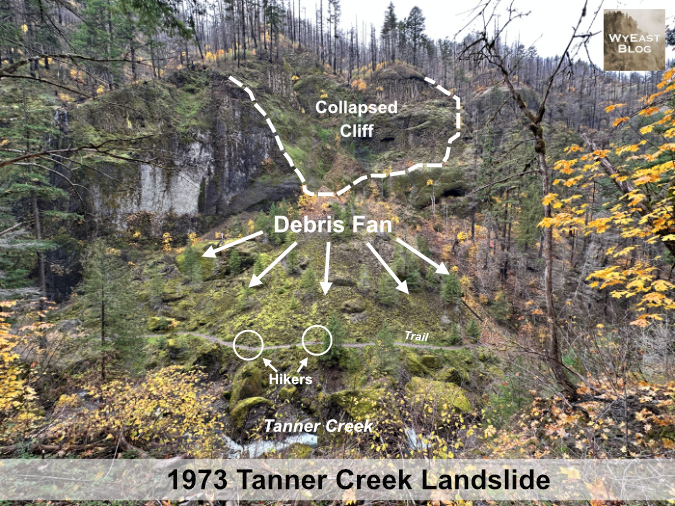

This schematic view (below) is from farther upstream on the main trail, just below Wahclella Falls and directly opposite the landslide. It provides a better sense of what the west wall might have looked like before the collapse, based on the intact wall to the left. The collapsed area is now a hollowed amphitheater in the wall of the canyon, and it still sends rocks and debris down to the fan each year as the new cliff face continues to weather and spall from exposure to the elements. The stand of mature Douglas fir to the right survived the event, marking the edge of the new debris, though these trees also grow on a talus slope created by some earlier event in Tanner Creek’s continued evolution. Two groups of hikers are circled to provide scale.

[click here to open a large version in a new tab]

Tanner creek can also be seen at the bottom of the schematic, where it tumbles through house-sized chunks of collapsed cliff that rolled into the stream during the event. At the time of the collapse, smaller, loose debris filled the voids between these giant boulders in the same way the large boulders remain buried in smaller material in the debris fan today. Tanner Creek quickly carved into the smaller material, clearing it away over the past 50 years and stranding the giant boulders in the creek bed.

The next schematic of the landslide (below) is from the lower part of the loop trail, where it crosses the debris fan and where the hikers appear in the previous schematic. This view gives a better sense of the smaller debris, from small, loose basalt fragments to boulders ranging from a foot across to as much as 25 feet across. The amphitheater formed in the cliff wall is more evident from this perspective, as well.

Over the half-century since the collapse, this part of the debris field has settled into a talus slope and is now fairly stable where it is out of reach of Tanner Creek.

[click here to open a large version in a new tab]

Along with the moss and Licorice Fern that now carpet much of the talus in the debris fan, a few Douglas Fir have become established over the half-century since the collapse, along with scattered understory plants like Ocean Spray and Snowberry. Despite fifty years passing, however, the landslide remains a raw, rocky place that tells us the full recovery will take many more decades for the forest to fully reclaim this slope.

The following photo sequence shows the progressive forest recovery on the landslide from just 13 years after the event, when moss was just beginning to take hold, to 2011, when the east wall of the canyon had stabilized enough to become dense with young deciduous trees like Bigleaf Maple and Red Alder. The most recent view shows a thinned forest recovering from the Eagle Creek Fire that swept through in 2017, moderately burning several sections of the Tanner Creek canyon, including this slope.

Forest recovery over the years on the Tanner Creek landslide

[click here to open a large version in a new tab]

The arrows in this photo comparison show common reference points, each marking one of four very large boulders that haven’t moved since the 1973 event. Surprisingly, the tall Douglas fir along the left edge of these photos is the same tree, and one that has survived the many changes to the area over the past half century – though leaning toward Tanner Creek a bit in recent years.

Why was the east wall of the canyon affected by a landslide on the west side? That traces to the dammed-up stream and subsequent erosion as Tanner Creek worked its way around the pile of debris the landslide had pushed against the east slope. As constant stream erosion has gradually uncovered the massive boulders that line the creek, the boulders have forced the creek against the edges of the stream channel, undercutting slopes on both sides of the canyon as the channel continues to deepen.

The lower bridge on the Tanner Creek loop trail crosses the stream where soft Eagle Creek Formation is overlain by solid basalt flows and loose basalt debris

Though they seem immovable by their sheer size, Tanner Creek continues to gradually shift the giant boulders over time, as they lie directly on unstable Eagle Creek Formation that forms the creek bed. This soft, underlying formation can be easily seen from the lower footbridge (above) along the Wahcella Falls trail, with the collection of basalt landslide boulders resting on top of the formation where it has been exposed by the creek. As the creek erodes soft Eagle Creek Formation material under these boulders, they shift, which in turn shifts Tanner Creek, as well. This continually shifting action continues to actively undercut slopes on both sides of the canyon, triggering smaller active landslides in several spots.

This effect can be seen in the following view of the east slope showing one of several small landslides that has been triggered over the years as the Tanner Creek banks against the foot of the east slope to move around the boulder in the lower right.

Active landslide on the east side of the canyon where Tanner Creek has been pushed against the slope, undercutting it

Over time, even house-sized basalt boulder fall apart, and this is on display at Tanner Creek, too. The giant boulder shown in this image (below) split sometime in the early 2010s. By 2016 a large piece had split off and partially crumbled, falling off into the stream in several pieces. While weathering like this typically results from cracks in the basalt that are expanded over time by freezing and thawing, the uneven erosion of the underlying Eagle Creek Formation likely destabilized this boulder further, with the sheer weight of the rock eventually pulling it apart at the seams.

This giant boulder was split apart in the early 2010s when Tanner Creek eroded the Eagle Creek Formation material underneath

This comparison view (below) of the boulder in 2011 and 2016 shows the extent of the weathering that occurred, as well as how the collapse of the east portion of this boulder allowed Tanner Creek to more aggressively undercut the east slope of the canyon, behind the boulder, expanding an active landslide. The letters in this graphic mark reference points for comparing the views.

Split boulder comparison from 2011 and 2016

[click here to open a large version in a new tab]

This animation (below) of the same before and after views of the boulder give a better sense of how the adjacent slope on the east wall was destabilized when the boulder split, leaving the slope unsupported and exposing it to undercutting by Tanner Creek. This weather and erosion sequence might seem unusual to us, but it is a constant in the geologic shaping of the Gorge, playing out countless times along Tanner Creek and along other streams that continue to carve their way through layers of basalt.

Animated split boulder comparison from 2011-16

The 2017 Eagle Creek Fire introduced yet another erosional force to the Gorge streams by producing thousands of fallen trees that quickly became driftwood as they fell or were carried downhill by landslides. During high water season, Tanner Creek and other large streams in the Gorge are fully capable of moving mature logs down their course, often piling them in huge log jams along the way. In a powerful stream, these join with the current when the streams are raging to become battering rams and pry bars against the boulders they encounter along their path.

Tanner Creek is especially wild and wooly in the winter, easily capable of moving whole logs down its channel

Such is the case at Wahclella Falls, where an enormous jam of several hundred logs has piled up since the fire in the side channel just below the falls (next to the “Wahclella Cave”). These comparison photos (below) shows how dramatically the log jam has grown over subsequent years, from a 25-foot wide pile two years after the fire in 2019 to a 120-foot long pile just five years in 2022. A smaller logjam has since formed inside the splash pool, as well (indicated by the arrow near the falls in the second photo).

Despite the size of these log piles, they are temporary and will eventually be on the move. Their next stop will be the boulder garden created by the landslide, just out of view to the left, where they could significantly alter the changing stream channel there, once again.

Growth of the post-Eagle Creek Fire logjam at Wahcella Falls

[click here to open a large version in a new tab]

This view (below) of the main logjam at Wahclella Falls is looking downstream from the upper footbridge and shows the obstacle course of huge landslide boulders in the distance that these (and other) logs will eventually work their way through. When logs form a jam, the combination of their sheer weight and the water pressure building behind them can move very large boulders or simply divert Tanner Creek in a way that accelerates erosion under boulders resting in the streambed.

Post-fire logjam below Wahclella Falls

This view (blow) of the smaller logjam inside the Wahclella Falls splash pool shows these forces at work, with Tanner Creek continuing to add new logs and woody debris to the gap between these large boulders, where the stream once freely flowed. The hydraulic pressure behind these jams is immense during high water, allowing the logs to incrementally pry even large boulders like these loose, and thus rearrange the stream channel.

Smaller logjam within the Wahclella Falls splash pool

Logjams like these will continue to appear and grow for decades to come in the post-fire period in the Gorge. The very good news is that woody debris like this is an essential ingredient to healthy fish habitat for salmon and steelhead, a fairly recent discovery by stream biologists. The lack of fire in the Gorge over the past century has had the effect of starving streams of woody debris, so the new conditions that we are witnessing are, in fact, very old. This is what these streams had always looked like for millennia, before fire suppression began in the early 1900s.

What about the boulders at Wahclella Falls?

In writing this article, I’ve attempted to map the areas impacted by the 1973 landslide, including the many large boulders left behind in Tanner Creek. Without photos from before the slide, I’m not able to fully answer whether the iconic boulders immediately below the falls (as seen in the logjam comparisons, above) were part of the event, as some believe. However, I’m fairly certain they were not, and instead that they came from earlier, similar cliff collapse events long ago.

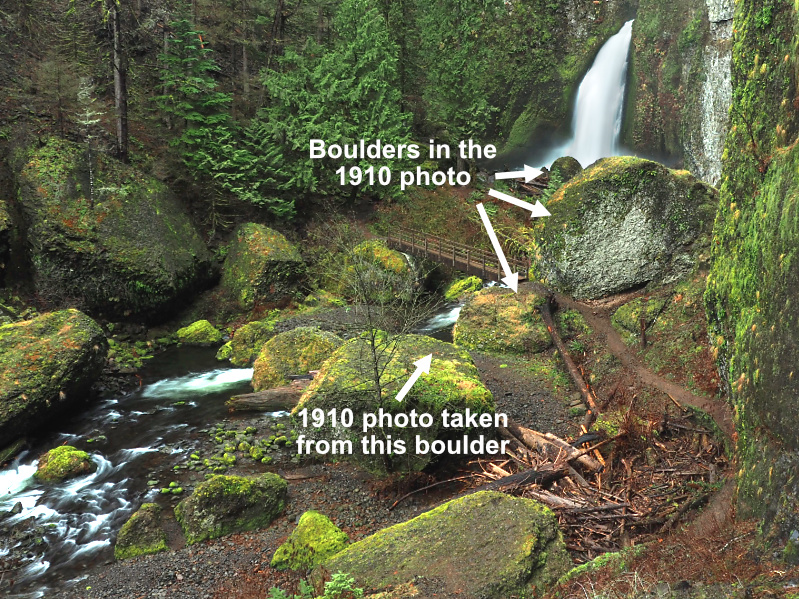

I do have a single historic photo of Tanner Creek (below), titled “Tanner Creek Falls in 1910”. If this is an image from a century ago, then it shows most of the boulders located immediately below Wahclella Falls to have been in place long before the 1973 landslide. The timing of the photo corresponds to construction of the Bonneville Fish Hatchery and accompanying diversion dam on Tanner Creek, so there’s a good chance it was captured during that period of intense activity in the area.

Wahclella Falls in 1910

While the 1910 photo doesn’t show much of the surrounding landscape, it does show the edge of a very large boulder that guards the west approach to the falls, immediately adjacent to the modern trail. The following comparison shows the edge of the same boulder on the right, as well as a pair of boulders in front of the falls that also appear to date back to the 1910 photo.

Wahclella Falls over the course of a century – 1910-2015

[click here to open a large version in a new tab]

The angle of the 1910 photo also suggests that the flat-topped “island” boulder bounded by the side channel (and now by the logjam) is where the photographer was standing, since the rock in the lower right foreground of the 1910 photo is where the west end of the footbridge is located today. This is shown in the following image of the boulders surrounding Wahclella Falls, with at least four of these present at the time of the historic photo.

Are these boulders from the 17973 cliff collapse? Unlikely

Based on the shape of the debris fan (just out of view to the left in the above photo), I believe all of the large boulders in this view pre-date the 1973 cliff collapse and landslide, though I will continue to look for historic photos that can document what really happened!

After the fire… and the future of Tanner Creek?

Since the fire in 2017, landslides have been active throughout the Eagle Creek Fire burn area. With no forest cover to moderate runoff, tributary streams flood more frequently, and as the killed trees begin to decay, their roots will no longer hold the steep Gorge slopes in place. Fortunately, the forest is already bouncing back, and these erosion effects will eventually fade, but in the meantime slides and erosion will continue to have a real impact – especially on hiking trails.

Small post-fire landslides like this one on the Wahclella Falls trail are keeping trail volunteers busy throughout the Gorge

What is less known is whether the loss of forest cover will trigger much larger events – like the massive cliff collapse that occurred at Punch Bowl Falls on Eagle Creek shortly after the fire. Given the amount of earth movement already happening on a smaller scale throughout the burn, it does seem likely that something larger might also be triggered. Perhaps this will happen at Tanner Creek? So far, there’s no way to know or predict future events of this scale.

Larger landslides like this one on the Wahclella Falls trail are moving whole trees burned in the fire into the stream

Meanwhile, Gorge visitation has never been greater, especially in the years after the pandemic, when interest in hiking soared across the country. At Tanner Creek, the combined effect of post-fire erosion and record crowds year-around has taken a visible toll on the landscape. Though the area was added to the Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness in 2009 to better protect it, Tanner Creek feels more like the popular state parks in “waterfall alley” on busy days than a “wilderness”. Large groups that greatly exceed the wilderness party limit of 12 are commonplace, and the small parking area at the trailhead overflows year-round, with cars parked along the freeway off-ramp on especially busy weekends.

Weekend crowds at the upper footbridge on the Wahclella Falls trail

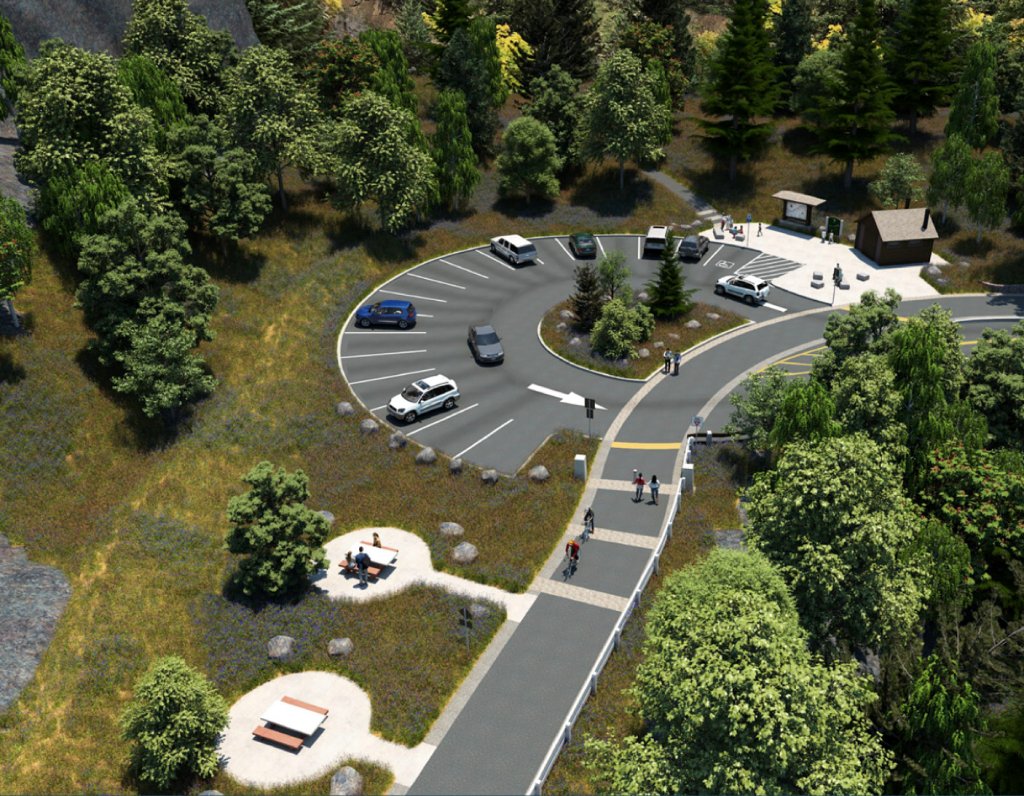

For its part, the Forest Service has expanded amenities somewhat at the trailhead, including a growing collection of portable toilets and even periodic law enforcement visits in response to frequent car break-ins. So far, the hiking experience remains exceptional, despite the crowds and their visible impacts. The trail to Wahclella Falls is considered family-friendly, so many of the visitors here are children who (hopefully) will come back to this as their own cherished spot for decades to come. That is perhaps the best way to ensure places like this are well-cared for in the future.

Contractors servicing the array of portable toilets at the Wahclella Falls trailhead

In addition to the parking area basics like toilets, I would like to see more interpretive information on the 1973 landslide provided at Wahclella Falls. The wilderness designation means that any signage along the trail must be minimal and rustic in design, but there is plenty of space at the parking area or the formal trailhead near the hatchery dam to provide more information on both the unique natural history of the area and a simple map of the trail – many hikers I encounter here don’t realize it’s a loop, and I finding them standing puzzled at the unsigned loop junction, unsure of which way to go (“take the lower trail, it’s a loop” I tell them).

Lines form for selfie photos in front of Wahclella Falls on busy days

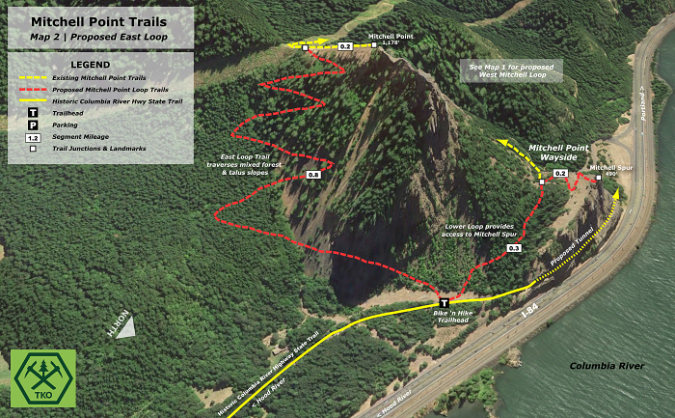

Looking to the broader future, my hope is that new trails and destinations will be opened in the Gorge to take some pressure off places like Tanner Creek. I’ve posted some ideas here over the years, and I will continue to make the case for more trails (including expanding the trails at Tanner Creek to new destinations upstream… watch for a future article on that topic!)

I’ve been hiking in the Gorge since I was in kindergarten, so I have the benefit of seeing the many changes to the area over time – whether they be natural events like the Tanner Creek landslide, or human-caused. That’s why this quote in the 1980 Lowe field guide caught my eye:

_________________

“The serene glade of cedar at the base of the Wahclella Falls is ample reward for the precarious stretches. You’ll probably want to spend extra time enjoying the sylvan setting.”

_________________

This description then came to mind when I was preparing this article, and ran across an image (below) from a hike to Wahclella Falls some 21 years ago, taken with my first digital camera in the fall of 2002. It was truly “serene glade” back then, and it still is – despite some signs of overuse that have since appeared.

Wahclella Falls in 2002 when the impact of hikers was still minimal

We don’t know what the forces of nature have in store for Tanner Creek in coming years, but the landscape continues to be in a state of dynamic change fifty years after the great landslide in 1973, and it will continue to change. But as the landscape continues to recover from the landslide – and now, the 2017 fire – we can do our part to ensure that this remarkable spot continues to be a place where we can watch the recovery unfold while also managing our own impacts, and allow some of the scars humans have caused to heal, as well.

________________

Tom Kloster | November 2023