Spring and early summer in the Gorge and around Mount Hood brings countless wildflowers. Perhaps the most striking are the varied siblings of the Lily family that are so familiar to us. This list includes the stately Trillium in early spring, the spectacular white trumpets of the Washington (or is it Mount Hood?) Lily, the blazing Columbia Tiger Lily in early summer and sprawling mountain meadows of Beargrass and Cornflower in high summer. All of these iconic species are part of this impressive family of wildflowers.

Within this crowded list of celebrity siblings are a trio of smaller lilies in the Erythronium genus that can be a bit confusing to distinguish from one another. They are surely worth getting to know: the yellow Glacier Lily, white Avalanche Lily and cream-colored Oregon Fawn Lily are among the most charming wildflowers found in our wild places. This article offers a profile of each of these plants, tips for identifying them and places to see them in their native habitat.

Oregon Fawn Lily

Erythronium oregonum

First up from this trio of lilies is the Oregon Fawn Lily, the largest of the Erythronium genus, and perhaps the most elegant. The Fawn Lily grows at low elevations, preferring open forest and meadows in the Coast Range, Cascade and Siskiyou canyons and foothills.

Oregon Fawn Lily have beautifully marked 4-9″ leaves, with a mottled pattern of green, light green and rusty brown that gives these plants their other common name of Trout Lily. These distinctive leaves are the easiest way to identify Fawn Lily. Their graceful blossoms form in clusters of 1-3 per stem, and range in color from white to cream, with yellow anthers. Each flower measures 1-3″ across on stems that range in height from 6-16″.

Oregon Fawn Lily blooms from April through early June. Like all of the Erythronium species, Oregon Fawn Lily emerges from a small bulb in spring and dies back in late summer after producing a 3-sided seed pod, going dormant for the winter.

A reliable place to spot Oregon Fawn Lily is along the Salmon River Trail, where they grace mossy slopes and cliff gardens in the lower sections of the canyon. They can also be found closer to home at the Camassia Nature Preserve in West Linn.

Avalanche Lily

Erythronium montanum

As the common name suggests, Avalanche Lily grows in mountain snow zones, preferring alpine and subalpine forests and meadows. These are among the first flowers to bloom after the snow melts, often forming dramatic carpets with their white, nodding flowers.

In Oregon, Avalanche Lily has been reported in the northern and central Oregon Cascades, along the high ridges of our basin-and-range country and on a remote outpost on Saddle Mountain, near Astoria (USDA)

Avalanche Lily flowers are white with a yellow base, and thus similar in appearance to Oregon Fawn Lily. But Avalanche Lily is much smaller, growing just 6-8″ tall — an adaptation to their harsh mountain habitat. Their leaves are bright green, shiny and strap-shaped, growing 4-8″ long and 1/2″ wide. Notably, they lack the mottled leaf pattern of the Oregon Fawn Lily, the surest way to distinguish between these species.

By the time most hikers make it into the high country in mid-summer, Avalanche Lily blooms have often faded, and have been replaced by distinctive 3-sided seedpods that will ripen by late summer. Like the Oregon Fawn Lily, Avalanche Lily dies back in fall after forming a seedpod and goes dormant, with their underground bulb safely insulated from winter weather.

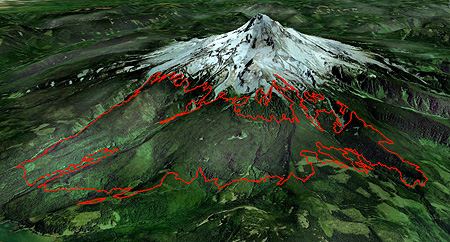

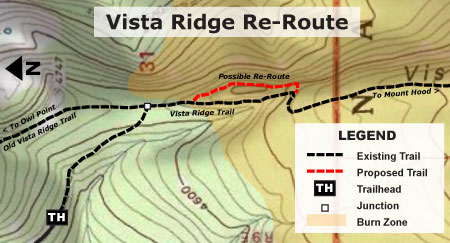

Their bulbs give lilies a distinctive advantage in fire zones, as witnessed after Mount Hood’s Dollar Lake Fire, in 2011. After the winter snows had cleared from the burn in 2012, avalanche lilies emerged from the charred landscape to burst into bloom, once again – their bulbs unaffected by the heat of the fire. Surprisingly, their bulbs are also an important food for bears in areas where Avalanche Lilies grow in abundance.

Avalanche Lily can be found along much of the Timberline Trail and its approaches in early summer. The upper section of the Mazama Trail, in particular, has the reliably prolific display.

Glacier Lily

Erythronium grandiflorum

The third in the trio of Erythronium lilies is the Glacier Lily, a distinctive little plant with bright yellow flowers. These are generally alpine and subalpine meadow flowers, but in Oregon, they also thrive in the Columbia River Gorge, where they seek out mossy outcrops, hanging meadows and forest margins.

Glacier Lily is so abundant in the Gorge that hikers who haven’t seen them in their more typical mountain setting probably wonder about their common name. But in alpine areas, Glacier Lily is found in the same habitat as Avalanche Lily, where they are among the first flowers to emerge and bloom after snowmelt.

Glacier Lily has the greatest range of the Erythronium lilies and are found throughout the Mountain West (USDA)

The leaves and growth habit of Glacier Lily looks much like those of their cousin, the Avalanche Lily. Their leaves are bright green, 4-8″ in length and about 1/2″ wide. Their stems are typically 6-12″, though tiny, stunted versions growing just 2-3″ in height can be found in more exposed locations in the Columbia Gorge.

Glacier Lily flowers are carried one or two per stem, and are typically lemon yellow, with cream or yellow anthers. Like the Avalanche Lily, these early blooming plants produce a seedpod by late summer, then die back to their bulb and go dormant before re-emerging the following spring.

A favorite habitat for Glacier Lilies in the Columbia Gorge is atop boulders, like this one along Moffett Creek, where they form blooming, yellow “caps” in spring

Their distinctive yellow color makes it easy to differentiate Glacier Lily from the white-flowered Avalanche Lily and Fawn Lily, but there’s a catch: it turns out a surprisingly similar flower from the Fritillaria family known as Yellow Bells does a pretty good job of masquerading as a Glacier Lily at first glance. In the Columbia Gorge, the two flowers commonly grow in close proximity, and bloom at about the same time, making it easy to confuse the two.

Yellow Bells are a member of the Fritillaria family, and often grow in close proximity to Glacier Lily in the Columbia Gorge

But upon closer inspection, the flowers are quite different. Where Glacier Lily matures to form open, flared blossoms, Yellow Bells behave true to their name, with a tight, bell-shaped blossom and straight petals. Once you spot this difference, it’s easy to distinguish between these similar neighbors at a glance.

Glacier Lilies can be found in April and early May on most Gorge trails that traverse open slopes and steep meadows. One reliable place to see them is on the Lower Starvation Loop, where they are sprinkled across the hanging meadows in late April. For hardy hikers, they can also be seen in April on the airy crest of Munra Point.

______________________

Botanical note: sources for this article include the USDA, Mark Turner and Phyllis Gustafson’s Wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest and Russ Jolley’s Wildflowers of the Columbia Gorge.