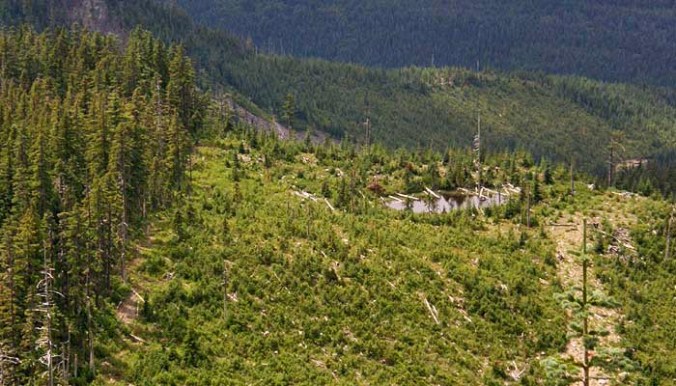

Dry Creek flows into a series of lush ponds just south of I-84.

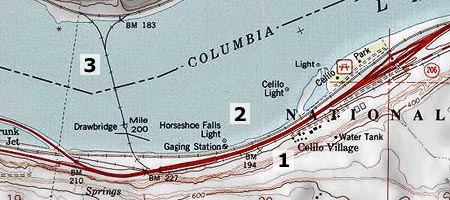

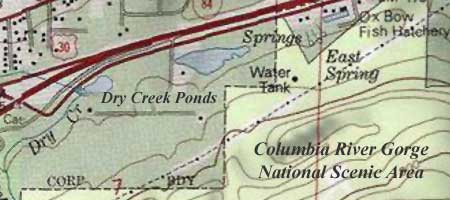

Just inside the city limits of Cascade Locks — and just outside the protection of the Columbia Gorge National Scenic area — lie a series of beautiful ponds and an adjacent group natural springs so pure that a national bottled water corporation is considering a new plant here. The ponds, themselves, are posted with real estate signs advertising dream home sites in this pretty location, albeit within earshot of noisy I-84.

The ponds underscore one of the dilemmas facing natural sites in the Columbia Gorge that happen to fall within the designated “urban areas” that are excluded from scenic area protection. Most of the Gorge towns are too small to have the fiscal means to protect these orphaned gems, even if they wanted to. Meanwhile, the non-profit organizations and federal agencies involved in land acquisition focus exclusively outside these urban areas. The result is a surprising number of natural features that face great risk of development, with no clear path for protection.

Dry Creek is better known for its waterfall, about a mile upstream from the ponds.

In the case of the Dry Creek Ponds, much of the land is already up for sale, and the real question is whether some sort of public purchase could intervene, and save the ponds from development. The ponds are not entirely pristine: a frontage road along I-84 borders one of the ponds, and there are a few homes tucked into the forest near the ponds. But the ponds are largely undeveloped, and surely worth more to the public as protected natural areas than to a few as exclusive home sites.

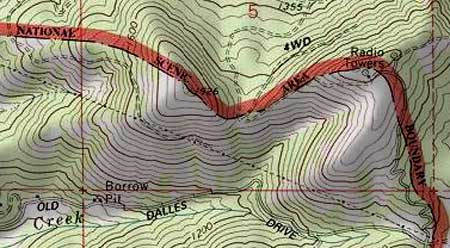

One option for protecting the ponds is the federal acquisition program operated by the Forest Service to consolidate lands within the scenic area. Their guidelines focus outside the urban areas, but a case could easily be made to cross those boundaries when natural sites are adjacent to surrounding public land. This is the case for the Dry Creek ponds, which not only abut the scenic area, but also the federal Oxbow fish hatchery.

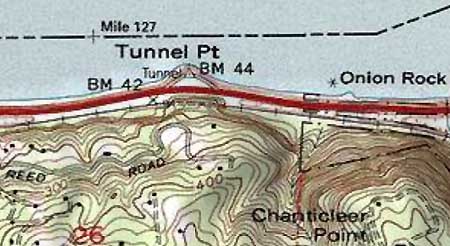

Dry Creek ponds are located outside the protection of both the National Scenic Area boundary and the nearby Oxbow fish hatchery.

A second option for protection are the private agencies involved in land acquisition within the scenic area. These organizations typically turn most of their acquisitions over to the federal government for long-management, so in the case of the Dry Creek Ponds, it would still be important to find a way for federal acquisitions to exist inside the urban areas.

A third option is for local governments to step up to the challenge, and create a municipal park or natural area for its local citizenry. In this case, the City of Cascade Locks is the local government in question, and like most of the small cities in the Gorge, is financially strapped. So a hybrid approach where the federal agencies, or perhaps the non-profits (or both) help the small cities make strategic acquisitions of places like the Dry Creek Ponds.

The ponds are teeming with wildlife, despite the noise of the nearby freeway.

One of the truisms about sudden growth in small communities like Cascade Locks is that the civic awareness of threats to natural areas usually comes too late in the development boom. After years of slow growth, Cascade Locks is slowly awakening. So, like other Gorge communities, the town is entering a short window of opportunity for natural area protection that will be fleeting.

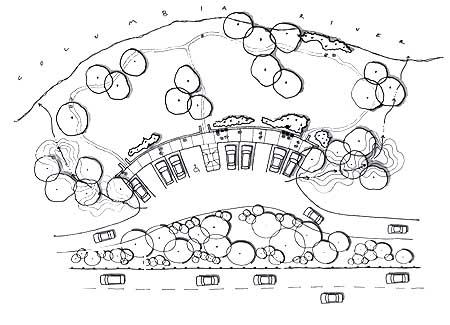

The Dry Creek Ponds are worth saving. The ponds are home to waterfowl, beaver and a thriving population of other species in the wetlands and forest that border the ponds. The ponds are unique in having such close proximity to Cascade Locks, and therefore easy access for visitors. This is one of only a few places in the Gorge where it is easy to get very close to a pond ecosystem, and thus could provide a valuable place for learning and wildlife watching.

Wetland birds thrive in tall marshes that border the ponds.

The ponds could also provide a starting point for hikers to head up Dry Creek to the falls — or points beyond along the Pacific Crest Trail, which passes just above the ponds, inside the scenic area.

In the end, the fate of the ponds will be a measure of our collective will to protect the larger Gorge landscape for generations to come, no matter where we’ve drawn lines on maps or how we have divided public land management responsibilities. In this way, the ponds provide an opportunity for local citizens, public land stewards and non-profit environmental advocates to show that our collective vision extends across those artificial boundaries.