Senator Mark O. Hatfield campaigning in 1967

One of the legacies of former Oregon Senator Mark O. Hatfield was expansion of the state’s wilderness system in 1978 and 1984, the largest expansion before or since that time. Though Hatfield was harshly criticized by conservationists for also sponsoring pro-logging legislation that led to the destruction of ancient forests, his role in creating new wilderness in Oregon remains a singular achievement that no other senator has yet matched.

To honor the senator, Congress renamed one of these new wilderness areas, the former Columbia Wilderness, as the Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness in 1996. This recognition marked the senator’s retirement from Congress after nearly a half century of public service that included serving as an Oregon legislator, Oregon’s Secretary of State, then Governor, before finally being elected to the U.S. Senate in 1967, where he served for 30 years

Senator Hatfield with wife Antoinette in 2008 (Willamette University)

The recognition also triggered another round of critiques by conservationists over Hatfield’s environmental legacy. But for many, it was also a fitting tribute to the senator who had pushed the Columbia River Gorge Scenic Act through Congress in the 1980s when it would have been easy for the Oregon Republican to simply leave the task to his Democratic counterparts.

Hatfield’s long service, and his independent stance on a number of topics, forced him to break ranks with the Republican Party on a number of progressive issues. These ranged from successfully sponsoring Oregon’s landmark civil rights legislation in 1954 (a full decade ahead of the U.S. Civil Rights Act) to his early opposition to American involvement in the Vietnam conflict, and later, the Gulf War.

His independence and principled “sanctity of life” stance that led him to champion civil rights for minorities and gays, while opposing wars, the death penalty and abortion later earned him his own chapter in Tom Brokaw’s “The Greatest Generation”.

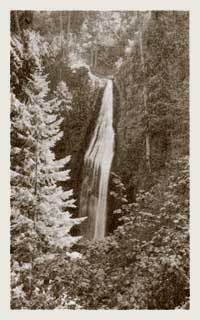

Multnomah Creek along the proposed Hatfield Trail

Though his environmental legacy is a conflicted one, Hatfield’s landmark environmental protections in Oregon still exceed that of his fellow Democrats, who claim the natural constituency of environmentalists, but have seldom acted with such determination and vision.

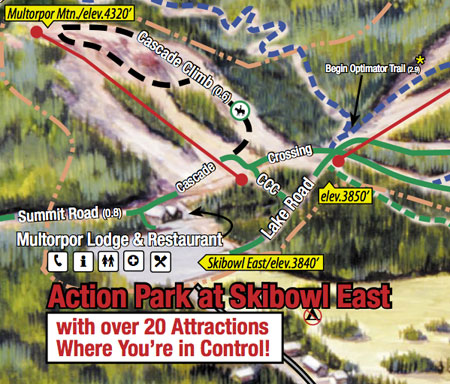

The Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness originally spanned the most remote high country on the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge, but in 2009, President Obama signed a new wilderness bill into law that expanded the Hatfield wilderness significantly. The new boundary stretches the Hatfield Wilderness from Larch Mountain and Multnomah Creek on the west to the steep ridges and canyons of Mount Defiance, on the east.

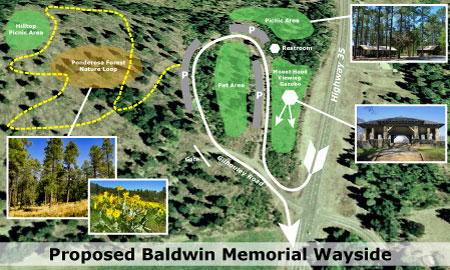

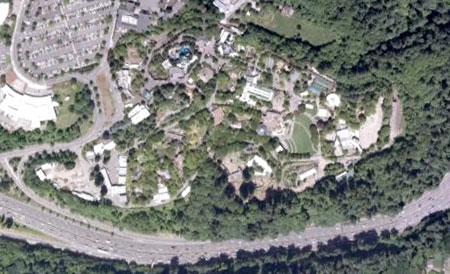

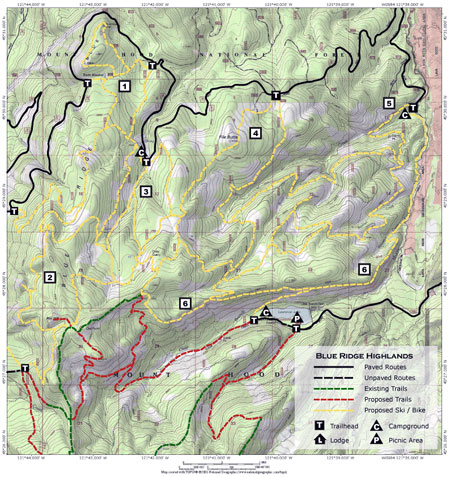

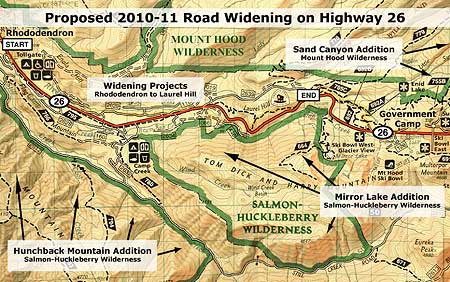

The Concept

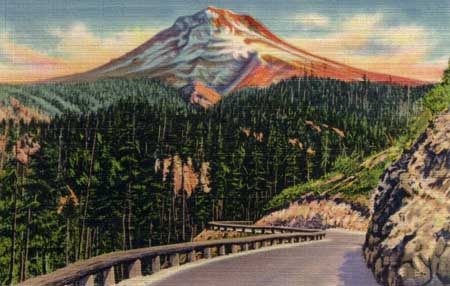

This Mark O. Hatfield Trail proposal is for a 60-mile memorial trail that spans the Hatfield Wilderness, beginning at Multnomah Falls and culminating at Starvation Creek Falls, passing through the most rugged, lonely country to be found in the Columbia River Gorge along the way. This new trail would join classic hikes like the Timberline Trail at Mount Hood and the Wonderland Trail at Mount Rainier as premier backpacking destinations of national prominence.

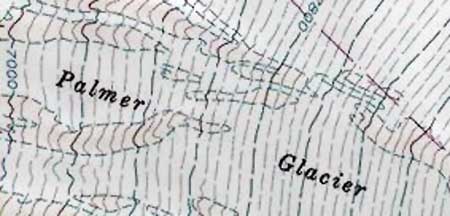

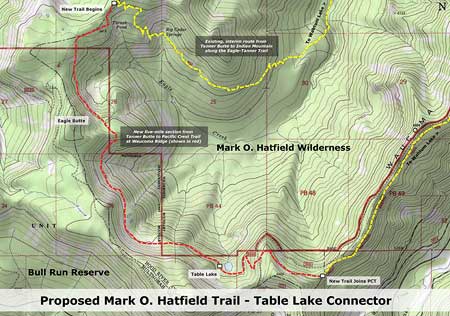

(click here to view a larger map)

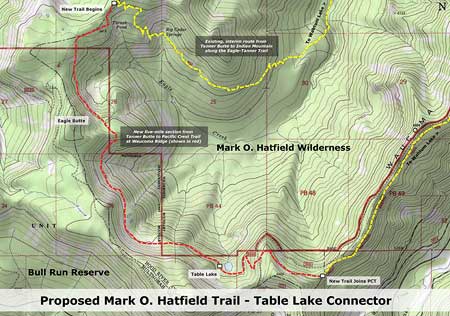

The new trail would largely be assembled from existing routes, but with a notable exception: a new, five-mile segment would curve just inside the Bull Run Reserve, along the headwaters of Eagle Creek. The new segment would bring hikers to little known Eagle Butte and rare views into the Eagle Creek backcountry that few have seen before.

Though this new trail segment would not physically enter the Bull Run watershed, it would nonetheless pass inside the reserve boundary. This would require special approval by the U.S. Forest Service, similar to that given the Pacific Crest Trail, where it crosses along the edge of Bull Run. Simply raising the issue might even challenge the absurd notion that trails and hikers present a risk to the watershed – a separate topic for another column!

Rugged Tanner Butte in the Hatfield Wilderness

Along the route, there are also many trails that would be “saved” by this proposal – routes that have been badly neglected for decades, but deserve to be maintained. In some spots, short realignments would be needed to improve old or confusing sections. In the area of Starvation Creek, for example, a redesigned trail along the final stretch near I-84 is needed to improve on the current, rather jarring re-entry into civilization.

The Trail

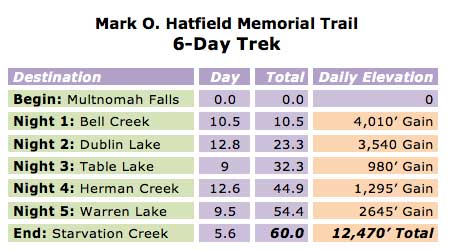

The 60-mile route is designed as a six-day trek, beginning at the Multnomah Falls Lodge, then leaving civilization behind for most of the next six days as the route traverses through the rugged high country of the Hatfield Wilderness.

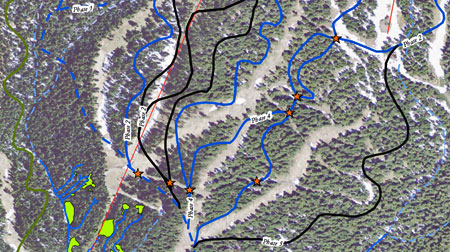

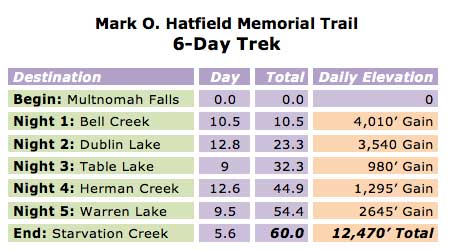

The following trip log shows the most prominent landmarks along the trail, with proposed camp spots for five nights on the trail. The up-and-down elevation changes inherent to the Hatfield Wilderness terrain will make this a challenging trek for any hiker. Segment and cumulative mileage is shown, along with net elevation gains and losses:

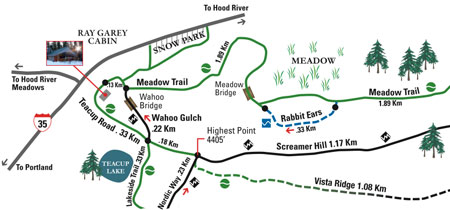

Day 1 to Bell Creek: the 60-mile trek would begin along the very popular Larch Mountain Trail, following Multnomah Creek beyond the reach of the throngs at Multnomah Falls, then climbing to historic Sherrard Point on Larch Mountain, another popular tourist destination. From here, the trail leaves the tourists behind, dropping into ancient forests along Bell Creek and the first campsite at 10.5 miles.

Day 2 to Dublin Lake: this is the most strenuous day along the circuit, covering 12.8 miles as the trail climbs over the shoulder of Nesmith Point, drops into Tanner Creek canyon, then climbs out again to arrive at Dublin Lake. At Nesmith Point, hikers can look down on the Columbia River nearly 4,000 feet below from the highest point on the Gorge rim, and on Van Ahn Rim hikers will get a rare look into the backcountry of the Tanner Creek canyon and into the Bull Run Reserve.

Indian Mountain with Eagle Butte in the distance

Day 3 to Table Lake: the third day of the proposed Hatfield Trail is a less challenging 9-mile hike along the high ridges of the Eagle Creek backcountry, allowing time for the spectacular side trip to Tanner Butte, along the way. The new trail segment begins north of Tanner Butte, and traverses across the rugged talus slopes and mountain tarns of Eagle Butte and Table Mountain, with expansive views into the Eagle Creek canyon, 3,000 feet below. The campsite for this proposed new segment is inside the Bull Run Reserve, at little-known Table Lake. Though the trail is inside the Bull Run boundary, the entirely of the trail is within the upper reaches of the Eagle Creek drainage, and is outside the physical watershed of the Bull Run.

Day 4 to Herman Creek: on the fourth day, the route joins the Pacific Crest Trail and passes high over the shoulder of Indian Mountain, then drops to popular Wahtum Lake. The lake provides a midpoint trailhead access for those looking for a shorter trip, an alternative camping spot or possibly a feed drop for those planning stock trips along the trail. From Wahtum Lake, the trail climbs over Anthill Ridge, then descends past Mud Lake before reaching a campsite at Herman Creek at the 12.6 miles.

Wahtum Lake from Anthill Ridge along the proposed Hatfield Trail

Day 5 to Warren Lake: this is also a less demanding day, with most of the climbing in the first few miles, as the route climbs out of the Herman Creek canyon, and passes the rocky summit of Green Point Mountain, with expansive views of the surrounding wilderness. From here, the route passes above Rainy, North and Bear lakes before curving around the rocky north face of Mount Defiance, then dropping to beautiful Warren Lake at 9.5 miles.

While the recommended circuit includes a night at Warren Lake to enjoy the exceptionally rugged setting and wilderness scenery, the relatively short, final leg to Starvation Creek will draw many hikers to make this a 5-day trip, and skip the final campsite at Warren Lake. For these hikers, the lake might simply offer the opportunity for a quick swim before heading back to civilization.

Bear Lake and Mount Defiance along the proposed Hatfield Trail

Day 6 to Starvation Creek: the short, 5.6 mile final leg travels steeply down the north slope of Mount Defiance along Starvation Ridge, dropping 3,600 feet in just over five miles. Along the way, the trail passes above dizzying cliff-top viewpoints and shady side-canyon waterfalls before reaching the Columbia River and the end of the trail at Starvation Creek.

The restrooms, telephone, easy highway access and shady, un-crowded streamside picnic sites below lofty Starvation Creek Falls make this an ideal terminus for hikers seeking to relax after their adventure.

The following table summarizes the recommended 6-day hike, with running mileage and daily elevation gains:

What would it take?

Much of the trail network described is exceptional in scenic value, but suffers from years of deferred maintenance and modernization. Since most of the route is already in place, the Mark O. Hatfield trail concept would mostly require a stepped up commitment to maintaining and improving existing routes.

This would include basic maintenance, like brushing out overgrown routes, tread repair and drainage, but would also new signage and log bridges across major streams, consistent with the Wilderness Act . This work could begin immediately, but will require funding, as the route is generally too remote and rugged to depend entirely on volunteer labor.

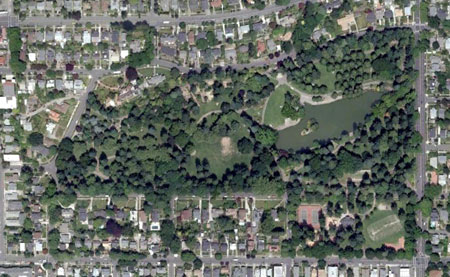

(Click here for a larger map of the new trail)

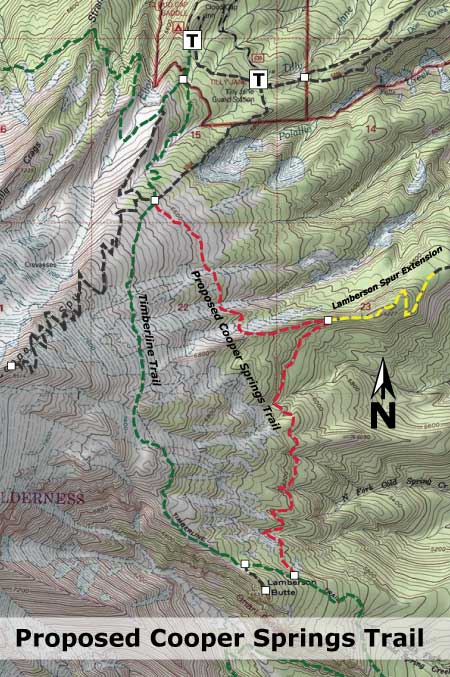

Constructing the new 5-mile segment proposed inside the Bull Run Reserve is the boldest element of this proposal, and a tall order for the federal bureaucracy. However, a simple interim plan is to route the new trail along the existing Eagle/Tanner (No. 433) and Indian Spring (No. 435) trails. These trails are shown in yellow on the map, above, and in green on the map showing the entire Hatfield Trail proposal.

This interim route would reduce the total hike distance by about two miles, and add about 1,000 feet of elevation gain. However, the interim option would allow for full implementation the Hatfield Trail concept in the near term, rather than waiting for the bureaucracy to address the watershed issue.

Columbia River from rugged Mount Defiance, near Warren Lake

(Click here for a large view of the panorama)

Another possibility for the long term is to finally complete the long-stalled Gorge Trail (No. 400) connection from Wyeth to Starvation Creek. This missing piece is a segment that would curve around the steep face of Shellrock Mountain (the focus of a future WyEast Blog article), creating a 30-mile trail connection from Multnomah Falls to Starvation Creek.

This connection would allow for a loop hike for hardy backpackers looking for a 90-mile backpack. However, because substantial portions of the existing Gorge Trail 400 are exposed to freeway noise and other reminders of civilization, the loop is not included in the Mark O. Hatfield Trail concept.

Why now?

This isn’t a difficult project to realize, and it would pay fitting tribute to begin work on this concept in time for Senator Hatfield to personally see the project begin – possibly even to participate in the ground breaking.

Accomplishing this project would be well-deserved recognition for the heavy lifting he did as our senator to protect the Columbia Gorge and Oregon’s wilderness for generations to come. The better question: why not now?