Along their return trip across the continent, on April 10, 1806, the Lewis and Clark expedition visited a small Indian village on what is now Bradford Island, in the heart of the Columbia River Gorge. Here, they traded for a beautiful white hide from what we now know as a Rocky Mountain Goat. Meriwether Lewis described it unmistakably in his journal as a “sheep”, white in color with black, pointed horns. The Bradford Island villagers told the expedition the hide had come from goat herds on the high cliffs to the south of what is now Bonneville, on the Oregon side.

Two days later, the expedition encountered another group of Indians, this time near present-day Skamania, on the Washington side of the river. A young Indian woman in the group was dressed in another stunning white hide, and this group also told of “great numbers of these animals” found in “large flocks among the steep rocks” on the Oregon side.

A century later, New York attorney Madison Grant produced the first comprehensive study of the Rocky Mountain Goat for the New York Zoological Society, in 1905. Grant described the historical range of the species extending from British Columbia south along the Cascade Crest to Mount Jefferson. At the time of his research, he reported that mountain goats had “long since vanished from Mt. Hood and from other peaks in the western part of the State, where they once abounded”.

Coincidentally, Grant’s report was published just a few years after the Mazamas mountaineering club formed on the summit of Mount Hood, selecting the Rocky Mountain Goat as their namesake and mascot — apparently, decades after the species had been hunted out in the Mount Hood region.

Another century later, on July 27, 2010, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) and Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs made history by releasing 45 Rocky Mountain Goats in the remote backcountry of Whitewater Canyon, on the east slopes of Mount Jefferson, just inside the Warm Springs Reservation.

The Mt. Jefferson release marked a symbolic and spiritual milestone for both conservationists and the Warm Springs Tribe, alike, restoring goats to their native range after nearly two centuries. The release also marked the first step in a major goat reintroduction effort, as envisioned in the landmark 2003 plan developed by ODFW to return goats to their former ranges throughout Oregon.

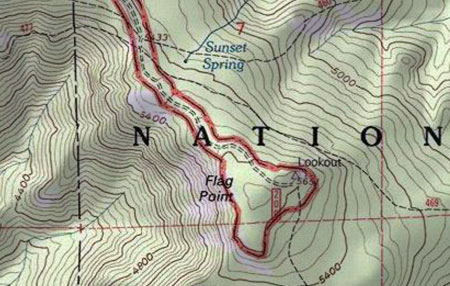

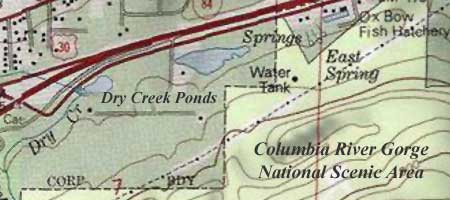

When the 2003 ODFW plan was developed, about 400 goats were established in the Wallowa and Elkhorn ranges, a few dozen in Hells Canyon, and a few scattered goats had dispersed just beyond these concentrations. The plan calls for moving goats from these established populations to historic ranges in the Oregon Cascades, including in the Columbia River Gorge. The proposed Gorge introduction sites include the rugged Herman Creek headwaters, the open slopes and ridges surrounding Tanner Butte and the sheer gorge face below Nesmith Point. The plan also calls for reintroducing goats at Three Fingered Jack and the Three Sisters in the Central Oregon Cascades.

The new effort to bring goats back to the Oregon Cascades is not without controversy. Conservation groups have taken the U.S. Forest Service and ODFW to court over lack of adequate environmental review of the plan to bring goats to the Gorge, and the agencies are now completing this work. The legal actions that have slowed the Gorge reintroductions helped move the Warm Springs effort forward, and are likely to move sites near Three Fingered Jack and the Three Sisters ahead of the Gorge, as well.

The 2003 reintroduction plan is also based on selling raffle-based hunting tags that fund the reintroduction program. This strategy is surprising to some, given the small number of animals surviving in Oregon. However, with the raffle for a single tag in 2010 raising nearly $25,000 for the program, it’s clear that selling hunting rights will help guarantee funding the reintroduction effort at a time when state budgets are especially tight.

Mountain Goats on Mount Hood?

The renewed interest in bringing mountain goats back to the Cascades, and the notable omission of Mount Hood from the ODFW plan as a release site, raises an obvious question: why not? The plan doesn’t provide details, but the likely arguments are lack of available habitat and the overwhelming presence of humans on Mount Hood.

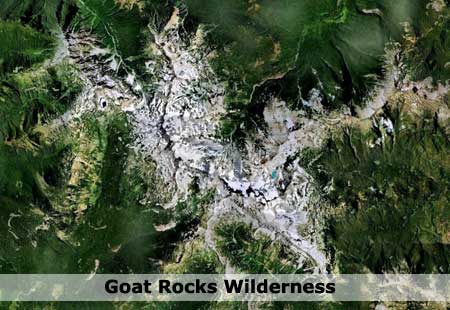

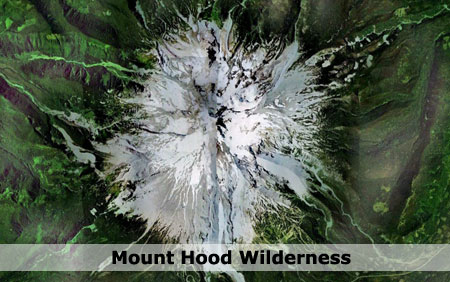

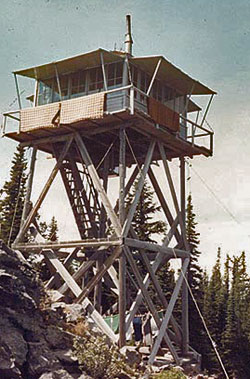

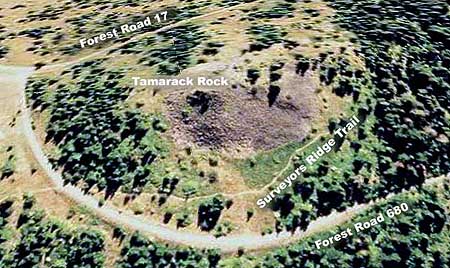

The ODFW plan prioritizes sites that can support at least 50 goats, including space for adult males to roam separately from herds of females and juveniles. Without knowing a specific acreage requirement for individual animals, the following comparison of Mount Hood to the Goat Rocks area helps provide perspective — with an estimated 300 mountain goats thriving at Goat Rocks. These images are at identical scale, showing comparative amounts of alpine terrain:

The Goat Rocks (above) clearly has more prime habitat terrain at the margins of timberline, thanks to the maze of ridges that make up the range. But in total alpine area, the Goat Rocks are not much larger than Mount Hood (below), so it appears that Mount Hood has the space and habitat for at least 50 goats.

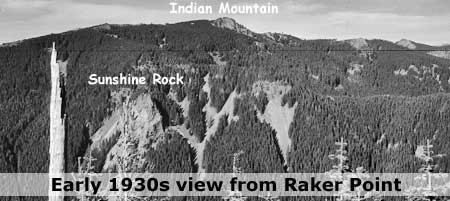

The human presence at Mount Hood is a more compelling argument against reintroducing goats. The south side of the mountain is busy year-round, thanks to three ski resorts, with lifts reaching high above timberline into what would otherwise be prime goat habitat. Snowshoers and Nordic skiers fill the less developed areas along the loop highway, making the south side one of the busiest winter sports areas in the region.

However, on the east, north and west sides of the mountain, human presence is mostly seasonal, limited to hikers in summer and fall along the Timberline Trail. These faces of the mountain have also been spared from development by the Mount Hood Wilderness, and thus offer long-term protection as relatively undisturbed habitat. This view of the mountain from the north gives a good sense of the many rugged alpine canyons and ridges that are rarely visited, and could offer high-quality goat habitat:

Since we know goats once thrived on Mount Hood, and adequate habitat seems to exist for goats to survive today, the real hurdle might simply be perception — that wildlife managers cannot imagine wild goats coexisting with the human presence that exists on some parts of the mountain. If so, we may miss a valuable opportunity to reintroduce goats where a large number visitors could view and appreciate these animals.

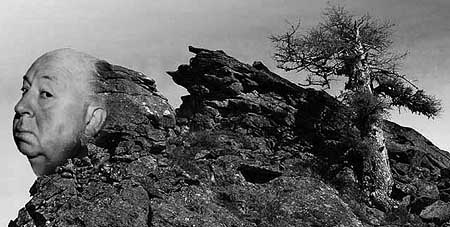

To help remedy this apparent blind spot, the following are a couple of digital renderings of what once was — and perhaps would could be — on Mount Hood. The first view is from Gnarl Ridge, on the east side of the mountain. Here, goats would find plenty of habitat in the high ramparts bordering the Newton Clark Glacier. This area is among the most remote on Mount Hood, so ideal for goats seeking a little privacy from human visitors:

The most obvious Mount Hood habitat is on the north side, on the remote, rocky slopes that border the Eliot, Coe and Ladd glaciers. This part of the mountain is only lightly visited above the Timberline Trail, and rarely visited in winter. It’s easy to picture goats making a home here, on the slopes of Cooper Spur:

(click here for a larger view)

Wildlife managers probably have good reason for skepticism about bringing goats back to Mount Hood. After all, the risks are clearly greater here than at less developed sites.

But let’s reverse these arguments: what if mountain goats were viewed as an end goal in restoring Mount Hood? What if this challenge were reframed as “what would it take for mountain goats to thrive here?” What if successful restoration of Mount Hood’s ecosystems were simply defined by the ability to support an iconic native species like the mountain goat, once again?

________________________

To read an Oregonian article (PDF) on the 2010 Mt. Jefferson goat release, click here.