When President Barack Obama signed the Omnibus Public Lands Management Act of 2009 into law on March 30, 2009, more than a dozen new pocket wilderness areas and additions to existing wilderness were created around Mount Hood and in the Clackamas watershed.

Among these, the Richard L. Kohnstamm Memorial Area expanded the Mount Hood Wilderness to the east of Timberline Lodge to encompass the White River canyon, extending from Mount Hood’s crater to about the 5,000 foot level, including a segment of the Timberline Trail and Pacific Crest Trail that traverses the canyon. This wilderness addition was created to “recognize the balance between wild and developed areas in the national public lands system and to create a tribute to the man who saved Timberline Lodge.”

Richard Kohnstamm was the longtime force behind the RLK Company, operators of the Timberline Resort, which has a permit to operate the historic Timberline Lodge, which in turn is owned by the American public.

After his duty as a gunner during World War II, Kohnstamm returned home to earn his masters degree in social work from Columbia University. After college, he moved to Portland to take a job at a local social services non-profit. Soon after arriving here, he made a visit to Timberline Lodge, where he was immediately taken with the beauty of the massive building.

But Kohnstamm saw a tarnished jewel, as the lodge had quickly fallen into disrepair following its construction by the Works Progress Administration in 1937. The Forest Service had revoked the operating permit for the lodge and was looking for a new operator, and so began the Kohnstamm era at Timberline. By all accounts, he did, indeed, save the lodge.

Kohnstamm soon teamed with John Mills to found the Friends of Timberline, a non-profit dedicated to preservation of the history, art and architecture of the remarkable building. The unique partnership between the Forest Service, Friends of Timberline and the RLK Company to preserve the lodge in perpetuity continues to this day, and is known as the Timberline Triumvirate.

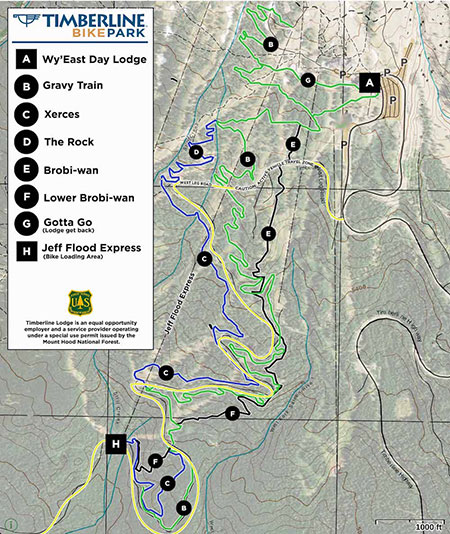

Today, the lodge continues to thrive, and summer resort operations have now expanded to include a controversial bike park centered on the Jeff Flood chairlift. After years of legal challenges, the RLK Company build miles of bicycle trails descending from main lodge to the base of the lift, where cyclists can load themselves and their bikes for a quick ride back to the top.

It’s a high-adrenaline activity made easy, with no hills to climb. But the development of this new attraction underscored the fact that the Timberline resort operators and Forest Service have done little over the decades to enhance the hiking experience around the lodge, despite plenty of demand.

The reason is pretty obvious: hikers don’t buy lift tickets. Yes, some hikers help fill the hotel rooms in summer, and still more stop by to support the restaurants in the lodge, but filling ski lifts continues to the focus at Timberline.

Today, hikers at Timberline are limited to walking along the Timberline Trail or hiking the Mountaineer Trail, a semi-loop that climbs to a lift terminal, where it dead-ends at a dirt service road. Hikers usually follow the steep, dusty road back to lodge to complete a loop.

But perhaps the Richard L Kohnstamm Memorial Area could be inspiration for the Forest Service and RLK Company to bring new trails to the area, and a create a more welcoming trailhead for visitors who aren’t staying at the lodging or paying to ride the resort lifts? In that spirit, the following is a concept for a new trail that would be an instant classic on the mountain, rivaled only by the popular Cooper Spur Trail on Mount Hood’s north side for elevation and close-up looks into an active glacier.

Proposal: Kohnstamm Glacier View Trail

The proposed Glacier View Trail would climb the broad ridge that separates the White River and Salmon River canyons, just east of Timberline Lodge. The new trail would begin just across the Salmon River from the lodge, at a junction along the Timberline Trail, and end at Glacier View, a scenic high point on the ridge between the Palmer and White River glaciers.

This viewpoint is already visited by a few intrepid explorers each year for its spectacular views into Mount Hood’s crater and the rugged crevasses of the White River Glacier. The schematic below shows how the new route would appear from Timberline Lodge:

Another perspective (below) of the proposed trail shows the route as it would appear from further east along the Timberline Trail, where it travels along the rim of White River canyon. This angle also shows the tumbling descent of the White River Glacier and the steep west wall of the canyon that would provide several overlooks from the new trail:

Thanks to the gentle, open terrain, the new trail would climb in broad, graded switchbacks, eventually reaching an elevation of 8,200 feet. This is just shy of the elevation of Cooper Spur, and would make the Kohnstamm Glacier View Trail the second-highest trail on the mountain.

The viewpoint at Glacier View (below) is already marked by a stone windbreak built by hikers that complements several handy boulders (below) to make this a fine spot for relaxing and taking in the view.

From the Glacier View viewpoint, Mount Hood’s crater and the upper reaches of the White River Glacier (below) are surprisingly rugged and impressive, given the generally gentle terrain of Mount Hood’s south side. From this perspective, the Steel Cliffs and Crater Rock dominate the view as they tower over the glacier.

But the scene-stealer is the White River Glacier, which stair-steps down a series of icefalls directly in front of Glacier View (below), providing a close-up look into the workings of an active glacier. Lucky hikers might even hear the glacier occasionally moving from this close-up perspective as it grinds its way down the mountain.

The view to the south from Glacier View (below) features the long, crevasse-fractured lower reaches of the White River Glacier, and below, the maze of sandy ravines which make up the sprawling White River Canyon. The deserts of Eastern Oregon are on the east (left) horizon from this perspective, and the Oregon Cascades spread out to the south.

The hike to Glacier View from Timberilne Lodge on the proposed Kohnstamm Trail would be about 2.5 miles long, climbing about 2,300 feet along the way, and would undoubtedly become a marquee hike on the mountain, if similar trails like Cooper Spur and McNeil Point are any gauge. But the backlog of trail needs at Timberline extend beyond having a marquee viewpoint hike like this.

The Kohnstamm trail concept therefore includes other trail improvements in the Timberline area that would round out the trail system here. The following schematic (below) include building a new 1.4 mile trail from the upper stub of the Mountaineer Trail to Timberline Lodge, allowing hikers to complete the popular loop without walking the dusty, somewhat miserable service road below Silcox hut, often dodging resort vehicles along the way.

The broader Kohnstamm trail concept also calls for using the east parking area as a day-hiking hub in the summer months, with clearly marked trailheads that would consolidate the maze of confusing user trails that are increasingly carving up the wildflower meadows here. The new hub would also include restrooms, interpretive displays, picnic tables and other hiker amenities that would make for a better hiking experience.

A more ambitious element of the concept is to convert the neglected bones of an abandoned lodge structure (above) at the east parking area to become a hiker’s hut where visitors could relax after a hike, fill water bottles or learn about hiking options from Mount Hood’s volunteer trail ambassadors.

This element might even tempt the Timberline resort operators to help make these trail concepts a reality if it offered an opportunity to provide concessions to hikers. After all, hiking is the fastest growing activity on the mountain (and on public lands), not skiing (or even mountain biking). Creating a hiking hub could be an opportunity for the Timberline operators to evolve their future vision for the resort to better match what people are coming to the mountain for.

What would it take?

Trail building is typically heavy work that involves clearing vegetation and building a smooth tread where rocks and roots are the rule. But the proposed Kohnstamm Trail would be very different, as the entire route is above the tree line and would be on the loose volcanic debris that makes up the smooth south side of Mount Hood. Trail building here would be much simpler, from the ease of surveying without trees and vegetation to get in the way, to actual trail construction in the soft soil surface. For these reasons, much of this work would be ideal for volunteers to help with.

In reality, the greatest obstacles to realizing this concept would likely be regulatory. Convincing the Forest Service to permit a new trail would be a tall hurdle, in itself. But if the Timberline resort operators were behind the idea, it would almost certainly be approved, especially if the resort embraced building and maintaining the trail hub improvements. Who knows, maybe they will even spot this article..?

Author’s Confessions…

As a postscript, I thought I’d post a few confessions from days of yore. I grew up in Portland and began skiing at Timberline Lodge as a tiny tot. I continued to avidly ski at the Mount Hood resorts for many years until giving up alpine skiing in the early 90s, largely in response to the expansion of the Meadows resort into lovely Heather Canyon, a deal-breaker for me. I loved the sport, but saw the beauty of the mountain under continual threat from the resort operations — and still do. Today, I make due with snow shoes and occasional trips on Nordic skis, though I do miss the thrill of alpine skiing!

An earlier awakening for me came in 1978, with the construction of the Palmer Lift at Timberline. This lift completed Richard Kohnstamm’s vision for year-round skiing on the mountain. But it was the first lift on Mount Hood to climb that far above the tree line, and was an immediate eyesore. Sadly, the conversion of the Palmer Glacier to become plowed rectangle of salted snow (see “Stop Salting the Palmer Glacier!”) that can be seen for miles completed the travesty.

That Palmer Lift debacle was soon followed by an even more egregious lift at Mount Bachelor, one that I wrote about 37 years ago in this (ahem!) riveting bit of self-righteous student journalism! (below)

When I stumbled across this old clipping from my days as a columnist at the Oregon State University student newspaper, I initially winced at the creative flourishes (…hey, I was 20 years old!). But my sentiments about these lifts — and the Heather Canyon lift at Meadows — remain unchanged. They were a step too far, and represented a real failure of the Forest Service to protect the mountain from over-development.

That said, I do believe the ski resorts can be managed in a more sustainable way that doesn’t harm the mountain. We’re certainly not there yet, and because all three of the major resorts (Timberline, Ski Bowl and Meadows) all sit on public land, I believe we all have a right to help determine that more sustainable future.

In this article, I’ve made a case for accommodating more than just lift ticket purchasers in the recreation vision at Timberline Lodge. In future articles I’ll make the case for rounding out the mission for the other resorts in a way that meets the broader interests of those of us who own the land.