Over nearly a century, a summer rite of passage for thousands of Oregonians has been wading through the vertical-walled Oneonta Gorge to the beautiful falls hidden at the head of this slot-canyon. Since 1914, the old Columbia River Highway has brought a steady stream of visitors to the tempting view into the gorge from atop a graceful bridge.

More recently, this tradition has been tarnished by a series of natural events that have made the trip up Oneonta Gorge downright dangerous. First, a rockfall near the entrance to the Gorge in the late 1990s that left three pickup-sized boulders in the stream. Then a logjam formed behind the boulders, creating a slippery maze that hundreds of visitors each summer now struggle to navigate. Sadly, the danger prevents many families with children from even attempting the trip.

Two weeks ago, Portlanders were reminded of the dangers of the logjam when 22-year old hiker Hassan Roussi tragically — and needlessly — drowned after slipping on the logjam. In the spirit of preventing another tragedy at Oneonta Gorge, this article proposes a few solutions that address both the safety and quality of experience for visitors to this uniquely beautiful place.

Phase 1: Log the Logjam

The logjam must go. Immediately. Just saw it out, with chainsaws. The log pile took one life this month, and that’s one too many. Add the many unreported accidents that have likely occurred here, and it’s long overdue to simply remove the hazard.

(click here for a larger version of this comparison)

Forget any excuses about ecological concerns, the stream playing out its natural processes or budget constraints. The arguments in favor of removing the logjam are simple:

Environmental Impacts: hundreds of visitors hike through Oneonta Gorge every summer, so the stream is only as pristine as a few hundred pairs of feet allow. Running chainsaws during an “in water” window, when salmon and steelhead are not spawning, would be no more disruptive than any of the in-stream activities that occur across the Mount Hood National Forest every year — from road projects and culvert repairs to timber harvesting.

Natural Systems: it’s true that Oneonta Creek has flushed logs from the drainage for millennia, so why one just let the natural order play out? One simple reason is public safety, of course. Unless the Forest Service is willing to close the gorge to visitors, then clearing the logjam is the only responsible option.

But there is also an economic argument against allowing the logjam to grow: eventually, it could burst during a flood event, pushing a wall of rock, logs and water against the pair of highway bridges and railroad bridge, 100 yards downstream. The result could be disastrous for these historic structures. Removing the logjam just makes sense for ODOT.

Budget Constraints: this is the standard argument for doing nothing in our national forests, but at some point, the agency will be held legally accountable for allowing recreation hazards like the logjam to persist. It might take that kind of shock to the system for the Forest Service to put recreation — and especially safety needs — ahead of other forest projects. Given the logjam has been accumulating since the 1990s, there has been plenty of opportunity for the agency to remedy this problem.

Though these signs are mostly intended to absolve the USFS from legal action, they don’t excuse the agency for allowing this hazard to accumulate

Since the boulders that created the logjam will likely take decades (or centuries) to move downstream from Oneonta Gorge, periodic logging out of accumulated debris is the obvious and appropriate action. It should happen this summer — with the recent tragedy as the impetus for fast-tracking this project. There really is no excuse for waiting.

This is completely within the scope and funding capability of the Forest Service, but could also be a joint responsibility shared with ODOT, given the risk the logjam represents for the highway bridges. It’s also a moral imperative for public agency stewards, given the risk to visitors, and the fatal outcome last week.

After the present logjam is cleared, it should be logged out regularly, perhaps every year or two. Just as other trails in the forest are cleared of winter downfall, Oneonta Gorge should be regularly cleared of dangerous logs.

Phase 2: Embrace the Bootpaths

The safety concerns at Oneonta Gorge aren’t limited to the logjam. Visitors to the area are naturally tempted by the view into the gorge from the historic Columbia River Highway bridge over Oneonta Creek, and an inviting stairway leads down from the bridge to the west bank of the stream.

Once at the bottom of the stairs, visitors usually follow a braided system of unofficial boot paths that climb along the west wall of the canyon, formed by thousands of feet that have tramped this way for decades.

Much of this path is a watery slog in the rainy months, ending in a slippery scramble over rock outcrops, but all of it is completely salvageable as a trail, with careful design and some tread work.

On the east side of the bridge, the Forest Service and ODOT have done their best to deny access to the stream, but with little success. Hikers have pushed beyond the piled logs and root wads at the “trailhead”, keeping the long-established route to the creek obvious and well-used.

Like the boot path along the west side of the creek, the east approach would be easily upgraded to a formal trail with a bit of design and tread work.

Nice try, but no dice: intrepid creek explorers aren’t stopped by this Forest Service blockade at the east approach to Oneonta Gorge

Together, the pair of boot paths flanking Oneonta Creek offer an excellent trail opportunity. Instead of trying to keep visitors out, a formal loop trail could safely bring less hardy hikers right to the mouth of Oneonta Gorge, while better managing some of the streamside impacts that the current maze of informal routes create.

The Proposal

Over the past decade, ODOT has spent a considerable amount restoring a section of the Historic Columbia River Highway at Oneonta Creek. The project included repaving the old highway and converting it to a hike/bike trail, with new parking for visitors and, most notably, restoring the old highway tunnel through Oneonta Bluff.

The highway restoration project was done beautifully, but many in the recreation community questioned the expense, given the many other unmet recreation needs in the area — the Oneonta logjam among them. Now is the time to backfill this project with trail improvements that connect the restored highway to the Oneonta Gorge — the main attraction in this area.

This proposal is simple: build on the beautiful restoration of the old highway and tunnel with a simple loop trail that follows the existing boot paths to the mouth of Oneonta Gorge. Coupled with removal of the logjam, these paths would lessen the impact of the many visitors who head up the gorge each summer. But the loop would also provide an excellent opportunity for less able hikers and families with children to take a short hike and see Oneonta Gorge, up close.

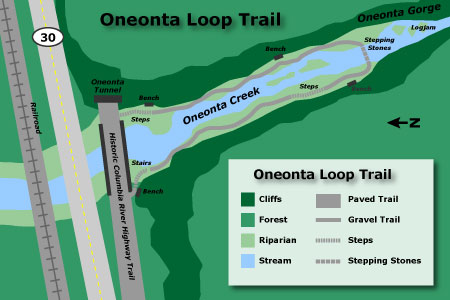

The following map shows the proposed loop trail:

[click here for a larger version of the map]

The loop would expand on several existing elements. First, it would take advantage of the historic stairway at the west end of the old highway bridge as the starting point for the loop, since most visitors already approach from this side of Oneonta Creek.

The stairway sets a wonderful rustic tone for the trail, more like a narrow footpath than a modern trail. This scale should be reflected in how the rest of the loop is designed, as it is perfectly scaled (and completely irresistible) to small children.

The stairway is in amazingly good repair, given the neglect it has suffered for nearly a century. Though at least one of the railing posts needs to be restored, the stairway is completely serviceable in its present condition.

The bench at the top of the stairs is another important design element, and would be repeated at three new locations along the proposed loop. If the tiny stairway is a perfect magnet for children, the bench is ideal for less able visitors who might walk a portion of the loop, or perhaps just the first few feet of the trail.

Using these basic design cues, the loop would formalize the boot paths on both sides of Oneonta Creek, with the new trail specifically designed for periodic flooding. This is because the entire riparian area between the walls of the gorge is subject to being submerged by high water, so trail elements would have to be designed accordingly.

An excellent design prototype already exists on another Columbia Gorge trail for accomplishing this all-weather design. The newly reconstructed trail at nearby Bridal Veil Falls provides an excellent blueprint for constructing a gravel-surfaced, flood-resistant trail. In the Bridal Veil design, the gravel trail is contained by a low border of basalt rocks (below).

The proposal also calls for steps at a couple of rock outcrops along the west side of Oneonta Creek, and where the loop connects to the old highway on the east side of the creek. These would be mortared steps, in the “CCC” style seen throughout the Columbia River Gorge.

The most unusual element of this trail proposal is the means of crossing Oneonta Creek, at the mouth of Oneonta Gorge. In low water months, this is a slippery rock hop for visitors, but with some careful design and periodic maintenance, it could be designed as a more formalized series of steppingstones, providing a safe crossing over a much longer season.

The steppingstone design would be a durable alternative to a conventional footbridge (which would not be appropriate in this location, given the visual impact), and would also be in tune with the rustic nature of the trail, itself. Depending on water levels and ability, hikers could opt to stop at the crossing, or venture across to complete the loop.

The Forest Service has also provided an excellent prototype for the steppingstone crossing, though not in the Columbia Gorge. Instead, the stream crossing pictured above, on the Clackamas River Trail, serves as an excellent blueprint. The stream flow in the scene is pictured in mid-winter, and similar to the summer flows on Oneonta Creek. A design like this is clearly feasible at Oneonta, though it would take periodic maintenance to ensure that steppingstones are adjusted or replaced, as needed, to maintain a safe crossing.

Finding a Creative Path Forward

Many of the ideas in these proposals require a break from conventional Forest Service practices, but “no action” at Oneonta Gorge isn’t a serious option. The Forest Service must address the logjam hazard, at a minimum.

The loop trail proposal would move the Oneonta area from a band-aid, substandard level of recreation support to an experience that could be a memorable highlight for many Columbia River Gorge visitors. The public should expect no less from our agency stewards.

How to get there? Clearly, the Forest Service must re-allocate funding to address the safety issue at the logjam, and soon. ODOT could be a partner in this effort, given their interest in protecting the highway bridges downstream.

But it’s also possible that ODOT or the Oregon State Parks could partner with the Forest Service in developing the loop trail. The work could also be underwritten by a corporate sponsor, given the high profile of Oneonta Gorge as a destination along the old highway.

The only limit at Oneonta Gorge is our imagination — and the willingness of our public land stewards to step up to the challenge. Now is the time.