Spring brings a stunning array of wildflowers to the Columbia River Gorge, and one of the most striking is the Money Plant (Lunaria annua), also known commonly as Silver Dollar Plant and Honesty. Its botanical name “lunaria” refers to its moon-shaped seed pods. But it turns out that Money Plant isn’t really a native — more about that in a moment.

This beautiful species produces lush purple, lilac and white blossoms on tall stalks in spring. But it is the namesake “silver dollar” seed pods — known as a “silique” — in fall and winter that are most familiar to us.

Money Plant typically grows in scattered roadside drifts, and can be found along the western sections of the Historic Columbia River Highway where it favors sites with rich soils and filtered sunlight.

Money Plant is a biennial, which means it takes two years to complete its lifecycle from germination to flowering and seed production.

In its first year the Money Plant sprouts from seeds in early spring, and over the course of summer develops leaves, stems, and roots substantial enough to survive the subsequent winter, when the plant becomes dormant.

In its second year, the Money Plant emerges from dormancy and “bolts” to produce tall flowering stems by late spring. The blossoms open from the bottom of the emerging stalk, and proceed to bloom at the growing tip of the flower stem, even as the earliest flowers have transformed into green, developing seed pods.

By early summer, most of the blooms have dropped, and the flower stalks have transformed into a bouquet of flat, green discs. These are the pods, or “siliques”, that hold developing seeds, and will soon mature to become the more familiar “silver dollars”.

“Dollars” are already forming on this plant, even as the tip of each flower stalk continues to bloom

By late summer of their second year, Money Plants have put all of their energy into producing viable seeds, whereupon the plant dies and turns a tawny brown as it dries.

Finally, the outer skin of each seed pod shrinks enough to become brittle, eventually popping off to release the seeds. Two to four flat, kidney-shaped seeds adhere to the pair of outer skins, allowing them to carried a short distance from the mother plant in the first fall storms, with the skin serving as a mini-sail.

Once the outer skins are shed from the seed pods, the Money Plant takes on its most familiar form. Each pod has an iridescent central membrane that dries to form the “silver dollar” that is reveled when the outer skins and seeds have been shed. These “dollars” remain on the plant through the winter and beyond, and even have commercial value as floral material.

Money Plant at the end of its lifecycle, with all of its seeds shed, leaving only a skeleton of the plant (source: Wikimedia)

Surprisingly… not native!

As non-natives go, Money Plant looks right at home among the native wildflowers of the Columbia Gorge. The plants are attractive, aren’t particularly aggressive and tend form only scattered small drifts among our native species.

It’s no secret how Money Plant naturalized: you can find Money Plant sold as a garden ornamental around the world, as the appeal of the plant is universal: showy flowers, attracts butterflies, valued for its dried form and easily grown from seed.

Thus, this native to the Balkans of Southeastern Europe has since naturalized throughout the world – including our own Columbia River Gorge.

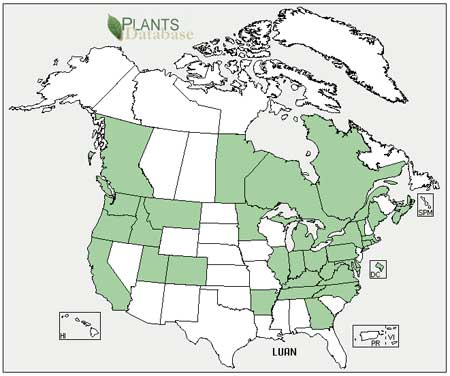

The following map shows Money Plant naturalizing in pretty much every temperate state, but notably where winters are cool enough to trigger its biennial growth stages:

In Oregon, the plant is listed as “moderately invasive” by numerous public land agencies and native plant organizations, though not on the “100 Worst List” of noxious species targeted by the State of Oregon for eradication.

Meanwhile, Money Plant seeds have found a new niche as a promotional gimmick, with marketers selling customized seed packets — most often for financial institutions, but also for other organizations.

It is therefore unlikely that Money Plant will ever be eradicated from Oregon — but also doesn’t seem to be a destructive invader. It thrives among native plants, but doesn’t seem to smother them. Compared to other, more aggressive invaders, Money Plant seems more “naturalized” than “invasive”.

Should you grow Money Plant?

So, now you’re feeling guilty about those Money Plant seeds you collected to plant in your garden, right? Clearly, millions of Americans have done the same — or simply purchased a pack of seeds at their local garden center (or received a pack from their bank – as I recently did).

Once planted, Money Plant is also very good at propagating itself in your garden – just as it does on roadsides. So, for most gardeners, that’s a benefit since the plant is a biennial and must be replanted annually, though that is also what makes the plant invasive.

So, is it okay to grow an “invasive” species..? Generally, the answer is “no”. But here’s a responsible way to grow Money Plant in your garden: simply cut the drying seed stalks (whether from your own garden, or collected in the wild) as they’re beginning to turn yellow, but before they’ve become brittle enough to release seeds. This prevents the seeds from scattering on their own, potentially beyond your garden.

Next, hang the cut plants in a garage or basement to completely dry. Once dried, you can shake the outer silique skins (and seeds) from the plants into a paper bag, and use the shiny inner “silver dollars” that remain on the stems for decoration. This allows you to collect and sow the seeds you harvest where you can keep an eye on the plants, and carefully control where the seeds go.

If you’ve collected your seeds in the wild, then you get bonus points: in addition to having some beautiful flowers in your garden, you’ve also done your part to keep the naturalized population in check, as well. That should go a long way in easing your guilt..!