Rock-star trail volunteer (and friend of the WyEast Blog!) Nate Zaremskiy has shared another update on the forest recovery in the upper Eagle Creek canyon, at the heart of the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia River Gorge (see Nate’s first batch of images in this earlier blog article). Nate captured these images in July as part of a Pacific Crest Trail Association (PCTA) trail stewardship effort to continue restoring the Eagle Creek trail.

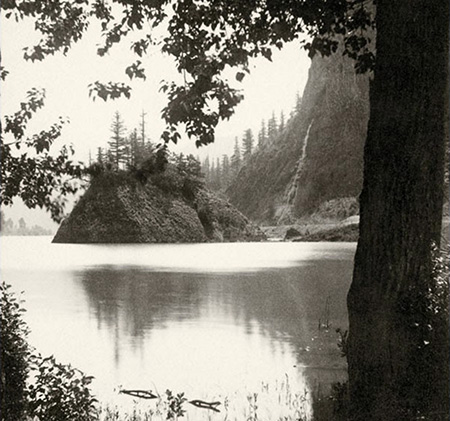

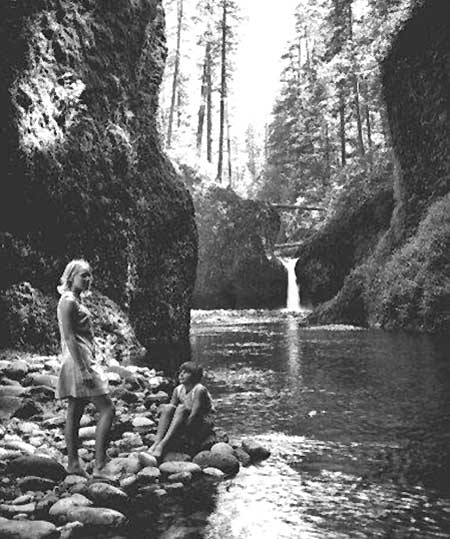

We’ll start with a visual rundown of some of the waterfalls that draw hikers to Eagle Creek from around the world. First up is Sevenmile Falls, a lesser-known falls at the head of the series of cascades on Eagle Creek. The fire was less intense here, with some of the forest canopy and intact and riparian zone along Eagle Creek rebounding quickly (below).

Moving downstream, the area around spectacular Twister Falls is recovering more slowly. The fire burned intensely on the rocky slopes flanking the falls, though many trees in the riparian strip upstream from the falls survived the fire (as seen in the distance in the photo, below).

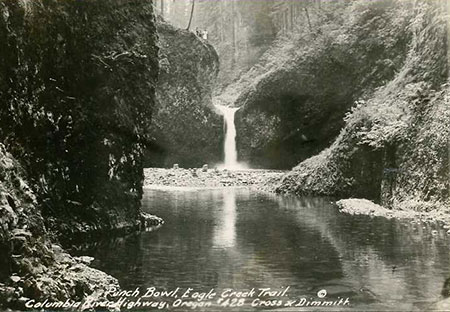

Tunnel Falls (opening photo) appears almost as if there had never been a fire, with the cliffs around the falls green and verdant. But a wider view of this spot would show an intensely burned forest above the falls that is only beginning to recover, as we saw in Nate’s earlier photos.

Continuing downstream, the next waterfall in the series is Grand Union Falls, a thundering just below the confluence of the East and main forks of Eagle Creek. The forest here largely dodged the fire, with many big conifers surviving along the stream corridor (below).

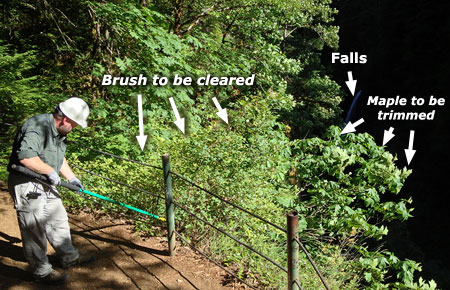

The handiwork of the PCTA crews can be seen in the above view of the infamous “basalt ledge”, where the Eagle Creek Trail is blasted uncomfortably through solid basalt columns along a sheer cliff face. The fire triggered a cliff collapse here, burying the trail in tons of rock. Over the past several months, PCTA volunteers meticulously cleared this section of trail, tipping huge boulders over the edge on at a time.

Nate’s photo update of the upper waterfalls ends here, but his new images also reveal an encouraging recovery underway in the burned forests of the upper Eagle Creek canyon. In moist side canyons the understory is rebounding in abundance, with familiar forest plants like Devils club, Sword fern and Lady fern covering the once-burned ground (below).

Lush understory recovery in a moist side canyon on the upper Eagle Creek Trail (Photo: Nathan Zaremskiy)

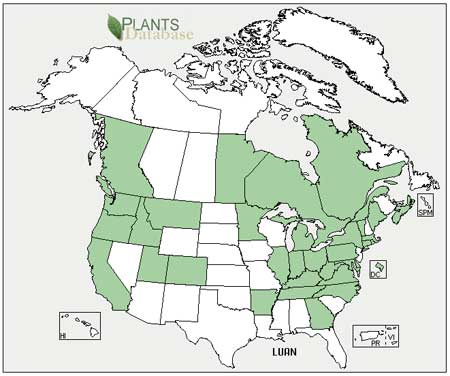

Along other, drier canyon slopes Fireweed (or “Firestar”? See “A Rose by any other name” on this blog) has exploded on the landscape, blanketing the burned soil as would be expected from this ultimate pioneer in forest fire recovery. Nate and his volunteers were sometimes shoulder-deep in Fireweed as they hiked along the upper sections of the Eagle Creek Trail (below).

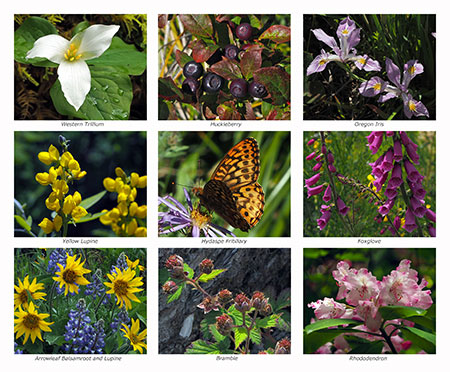

In other parts of the burn, the unburned roots and stems of the understory that survived the fire underground are now pushing new growth above the burned soil. Even in areas where no trees survived the flames, understory survivors like Vine Maple, Thimbleberry and Oregon grape can be seen in abundance in views like this (below):

Recovering understory in a heavily burned section of the upper Eagle Creek canyon (Photo: Nathan Zaremskiy)

Even the most intensely burned areas in the upper reaches of the Eagle Creek canyon are showing signs of life, with Oregon Grape, Salal and Ocean Spray emerging from roots that survived beneath the ashes (below).

Recovery is slower in the most intensely burned areas, but is still underway (Photo: Nathan Zaremskiy)

The forest recovery in the Eagle Creek burn is just beginning a cycle that has played out countless times before in Western Oregon forests, especially in the steep, thin-soiled country of the Columbia River Gorge. So, what can we expect as the recover continues to unfold? It turns out we have a good preview of things to come with a pair of recent burns in the Clackamas River canyon, fifty miles to the south, where the forests and terrain are very similar to the Gorge.

What’s next? Learning from the Clackamas Fires

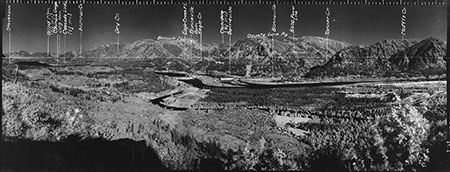

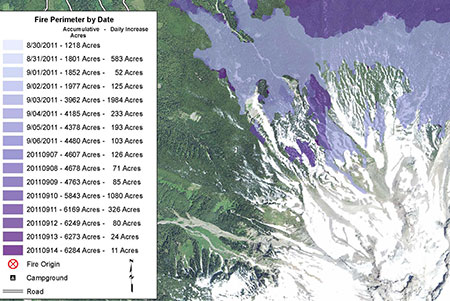

Two recent fires have swept through the steep-walled canyon of the lower Clackamas River. In 2014, the 36 Pit Fire burned 5,524-acres in the canyon. This was a scary September blaze that drew required 1,000 fire fighters to contain the fire from burning utility lines and toward homes near the town of Estacada. The 36 Pit Fire burned much of the South Fork Clackamas River canyon, a newly designated wilderness area, as well as several miles of the main Clackamas River canyon.

Like Eagle Creek, the 36 Pit Fire burn was the result of careless teenagers, in this case started by illegal target shooters. Five years later, this gives us a look at what the Eagle Creek burn will look like in another 3-4 years. The view below is typical of the 36 Pit Fire, with broadleaf understory species quickly recovering in the burned canyon.

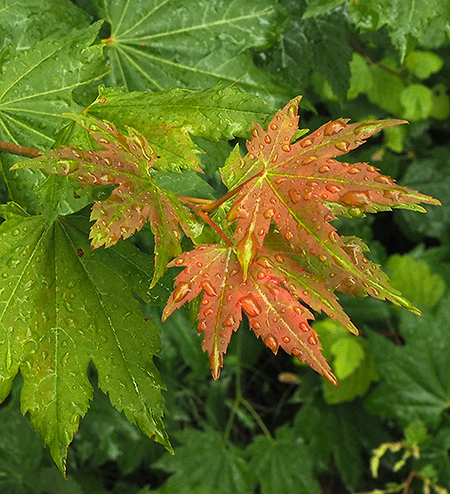

In this view (below) a trio of maples — Bigleaf maple, Douglas maple and Vine maple — dominate the recovery along a canyon slops. Most are growing from the surviving roots of trees whose tops were killed in the fire. This ability to recover from surviving roots gives broadleaf trees a leg up over conifers like Douglas fir.

Another scene (below) from the canyon floor shows how areas with more ground moisture have fared five years after the 36 Pit Fire. Here, the conifer overstory largely survived the fire, and even some of the broadleaf trees have survived, in part because the were less drought-stressed than trees higher up the slopes when the fire swept through. This is typical of burns and can be seen throughout the Eagle Creek burn, as well, with well-hydrated trees in moist areas better able to withstand the intense heat of the fire.

Here, Bigleaf maples on either side of the view are sprouting new growth from midway up their partially burned trunks. These damaged trunks of these trees may not survive over the long term, but most are also sprouting new shoots from their base — an insurance policy in their effort to survive. The understory throughout this part of the canyon floor is exploding with new growth from roots that largely survived the fire and benefit from the moisture here in their recovery. Thimbleberry (in the foreground) is especially prolific here.

The following scene (below) is also typical of the 36 Pit Fire at five years, with the conifer overstory mostly surviving the fire on this low slope, and the understory rejuvenated by the burn. When scientists describe a “beneficial” fire, this is an example of the benefits. Beneath the surviving conifers in this view, the white, skeletal trunks of burned Vine Maple and Red alder rise above vibrant new growth emerging from the roots of these trees. This lush new growth provides browse for deer, elk and other species, and new habitat for small wildlife, while also protecting the steep forest soils from erosion.

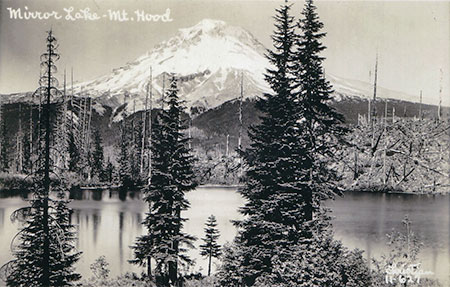

In September 2002, the much smaller Bowl Fire swept through 339 acres of mature forest along the west end of the Clackamas River Trail, just upstream from Fish Creek. Like the Eagle Creek and 36 Pit fires, the relatively small Bowl Fire was human-caused, with the ignition point along the Clackamas River Trail, likely by a hiker. More than 300 firefighters were called out to fight this blaze.

Fifteen years of recovery has transformed the canyon slopes burned in the Bowl Fire from black to lush green

Today, The Bowl Fire provides a look 15 years into the future for the Eagle Creek burn, and the rate of recovery here is striking. These views (above and below) from the heart of the Bowl Fire show 20-25 foot Bigleaf maple and Red alder thriving among the surviving conifers and burned snags. Vine maple, Douglas maple, Elderberry and even a few young Western red cedar complete this vibrant scene of forest rejuvenated by fire.

The forest recovery from the Bowl Fire give us a glimpse of what the burned areas of the Gorge will look like in another 10-12 years

Growing up in Oregon, I was taught that many of these broadleaf tree species that are leading the fire recovery in the Clackamas River canyon and at Eagle Creek were “trash trees”, good for firewood and little more. But as our society continues our crash course in the folly of fire suppression and ecological benefits of fire, these species are emerging as hard-working heroes in post-fire forest recovery.

The Unsung Heroes of Fire Recovery

It’s worth getting to know these trees as more than “trash trees”. Here are five of the most prominent heroes, beginning with Bigleaf maple (below). These impressive trees are iconic in the Pacific Northwest, and highly adaptable. They thrive as towering giants in rainforest canyons, where they are coated in moss and Licorice fern, but can also eke out a living in shaded pockets among the basalt cliffs of the dry deserts of the eastern Columbia River Gorge. Their secret is an ability to grow in sun or shade and endure our summer droughts.

As we’ve seen in the Gorge and Clackamas River canyon burns, Bigleaf maple roots are quite resistant to fire. Throughout the Bowl Fire and 36 Pit Fire, roots of thousands of burned Bigleaf maple have produced vigorous new shoots from their base, some of which will grow to become the multi-trunked Bigleaf maple that are so familiar to us (and providing some insight into how some of those multi-trunked trees got their start!). Their surviving roots and rapid recovery not only holds the forest soil together, their huge leaves also begin the process of rebuilding the forest duff layer that usually burns away in forest fires, another critical role these trees play in the fire cycle.

Vine maple (below) are perhaps the next most prominent tree emerging in the understory of the Bowl Fire and 36 Pit Fire. Like Bigleaf maple, they emerge from surviving roots of burned trees, but Vine maple have the added advantage of a sprawling growth habit (thus their name) when growing in shady forest settings, and these vine-like limbs often form roots wherever they touch the forest floor. When the exposed limbs are burned away by fire, each of these surviving, rooted sections can emerge as a new tree, forming several trees where one existed before the fire. Vine maples are abundant in the forest understory throughout the Cascades, so their survival and rapid recovery after fire is especially important in stabilizing burned slopes.

Douglas maple (below) is a close cousin to Vine maple and also fairly common in the Clackamas River canyon and Columbia River Gorge. What they lack in sheer number they make up for in strategic location, as these maples thrive in drier, sunnier locations than Vine maple, and these areas are often the slowest to recover after fire. Douglas maple emerging from the roots of burned trees on dry slopes can play an important niche role in stabilizing slopes and helping spur the recovery of the forest understory.

Red elderberry (below) are a shrub or small tree that is a common companion to the trio of maples in the recovering understory of the Clackamas River canyon. Like the maples, they often emerge from the surviving roots after fire. Elderberry also thrive in disturbed areas, so this species is also likely emerge as seedlings in a burn zone, as well.

This is probably as good a place as any to point out that the red berries of Red elderberry are not safe to eat. They contain an acid that can lead to cyanide poisoning in humans (did that get your attention?). However, the berries and leaves are an important food source for birds and wildlife, another important function of this species in a recovering forest.

One of the most prolific species emerging in the Clackamas River burn zone is Thimbleberry (below), a dense, woody shrub related to blackberries and another important food source for birds and wildlife after a fire. Their soft, fuzzy berries are also edible for humans, as most hikers know. Thimbleberry also appear in many of the recovery photos of the upper Eagle Creek canyon that Nate Zaremskiy shared.

Finally, a less welcome “hero” in the post-fire forest recovery (to us humans, at least) is Poison oak. This amazingly adaptable, rather handsome shrub (and vine — it can grow in both forms) is found throughout the Columbia River Gorge as well as the lower Clackamas River canyon. In this view (below), Poison oak is emerging in the Clackamas burn zone alongside Thimbleberry, shiny with the oil that causes so much havoc in humans.

Like the other pioneers of the recovery, Poison oak grows from surviving roots and seems to benefit from fire with renewed growth and vigor. Poison oak also likes filtered sun in forest margins, so a tree canopy thinned by fire can create a perfect habit for this species. Like Thimbleberry and Elderberry, Poison oak is (surprisingly) an important browse for deer in recovering forests.

Many other woody plants and hardy perennials also play an important role in the recovery of the forest understory, including Ocean spray, Oregon grape, Fireweed, ferns, and native grasses. These fast-growing, broad leafed plants are critical in quickly stabilized burned slopes, rebuilding a protective duff layer and providing shade and cover for wildlife to return.

So, if forests are so good at recovering from fire, can they recover from logging in much the same way? Read on.

Learning to be Part of the Fire Cycle?

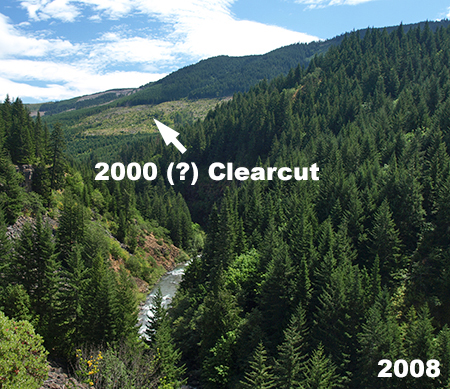

If logged-over forests were left to their own recovery process, they would follow much sequence as a burned forest, with the understory rebounding quickly. However, fire usually leaves both surviving overstory trees and standing dead wood that are critical in the recovery by helping regenerate the forest with seedlings from the surviving trees, habitat in the form of standing snags and by providing nutrients from fallen, decaying dead wood. But even with the overstory cut and hauled away as saw logs, a clearcut could still recover quickly if the understory… if it were simply allowed to regenerate this way.

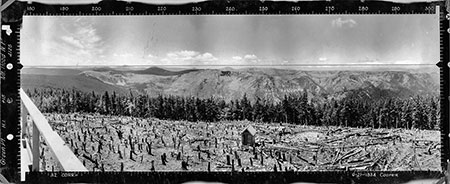

And therein lies the rub. Time is money to the logging industry, and they still view the broadleaf species that lead our forest recovery as “trash trees”, something to be piled up and burned in slash piles. So, the standard practice today is to shortcut the natural recovery process our forests have evolved to do, and simply kill the understory before it can even grow.

This is done by repeated helicopter spraying of clearcuts with massive amounts of herbicide after a forest has been cut, typically a year or two after the logging operation. This produces the brown dead zone that we are sadly familiar with in Oregon. Having killed the entire understory, cloned plantation conifers are then planted among the stumps with the goal of growing another round of marketable conifers in as short a period as possible. Time is money and trees are a “farm” not a forest to the logging industry.

These Douglas fir cultivars were bred for rapid growth and planted to shortcut a necessary stage in the recovery process, which is great for the corporate timber shareholders but very bad for forest health.

It doesn’t take a scientist to figure out that shortcutting the natural recovery process after logging also shortchanges the health of the forest over the long term, robbing the soil of nutrients that would normally be replaced in the recovery process and exposing the logged area to erosion and the introduction of invasive species (a rampant problem in clearcuts). Destroying the understory also robs a recovering clearcut of its ability to provide browse and cover for wildlife — ironically, one of the selling points the logging industry likes to use in its mass marketing defense of current logging practices.

In Oregon, this approach to fast-tracking forests is completely legal, though it is clearly very bad for our forests, streams and wildlife. As Oregon’s economy continues to diversify and become less reliant on the number of raw logs we can cut and export to other countries to actually mill (also a common practice in Oregon), cracks are beginning to form in the public tolerance for this practice. Most notably, private logging corporations are increasingly being held accountable for their herbicides entering streams and drifting into residential areas.

The understory in the uncut forest bordering this corporate logging operation shows what should be growing among the stumps, here. Instead, tiny first seedlings were planted after herbicides were used to kill everything else on this slope directly above the West Fork Hood River. This is standard forest practice in Oregon, sadly.

So, there’s some hope that the logging industry can someday evolve to embracing a natural recovery strategy, if only because they may not be able to afford the legal liability of pouring herbicides on our forests over the long term. Who knows, maybe the industry will eventually move to selective harvests and away from the practices of clearcutting if herbicides are either banned or simply too expensive to continue using?

The recent fires in the Columbia River Gorge, Mount Hood Wilderness and Clackamas River canyon may already be helping change industry our logging industry practices, too. These fires have all unfolded on greater Portland’s doorstep and have engulfed some of the most visited public lands in the Pacific Northwest.

While the initial public reaction was shock at seeing these forests burn, we are now seeing a broad public education and realization of the benefits of fire in our forests, with both surprise and awe in how quickly the forests are recovering.

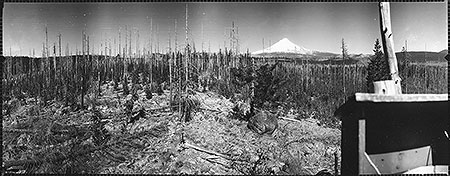

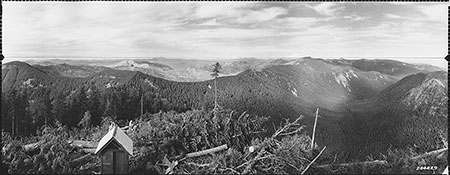

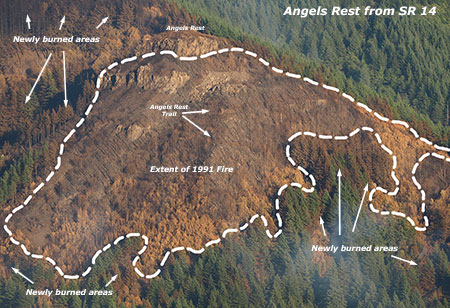

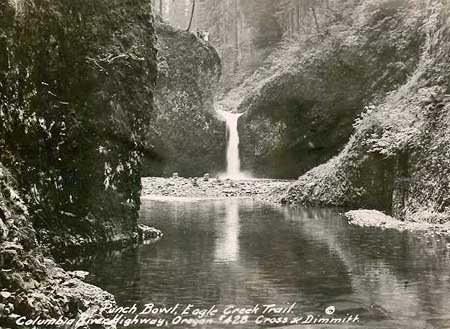

Skeletons from the 1991 Multnomah Falls fire rise above recovering forests in this scene taken before the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire, when part of this forest burned again to continue the fire and recovery cycle in the Gorge.

That’s good news, because a public that understands how forests really work is a good check against the corporate interests who fund the steady stream of print and broadcast media propaganda telling us how great industrial logging really is for everyone.

Are we at a tipping point where science and the public interest will finally govern how the logging industry operates in Oregon? Maybe. But there’s certainly no downside to the heightened public awareness and appreciation of the role of fires in our forests. We do seem to have turned that corner…