With the controversy (apparently) behind us on the now-defunct Cascade Locks casino proposal, conservationists have focused their Gorge concerns on a Nestle Corporation proposal: truck bottled water from a natural spring at a little-known fish hatchery on the edge of Cascade Locks (described in this WyEast Blog article)

The Nestle proposal is a bad idea on so many levels, and ought to be stopped. But the fracas over Nestles has overshadowed a very good idea known as the Cascade Locks International Mountain Bike Trail, or CLIMB. The concept is to simply build on the network of existing trails, old forest roads and a few new trails to create a world-class mountain biking destination, accessible from downtown of Cascade Locks.

This proposal is exactly the kind of quiet recreation-oriented tourism strategy that put Hood River back on the map after the timber collapse in the early 1980s, and has the potential to revitalize Cascade Locks as well. The former mill town of Oakridge has kicked off a similar effort to foster bike tourism, advertising itself as the “Mountain Biking Capital of Northwest”, and bringing an impressive network of trails online over just a few years. These communities provide working examples for Cascade Locks in making a successful transition to a tourism-based economy.

Conservationists should be enthusiastically supporting the CLIMB idea, and any others like it that build on the natural and scenic character of the Gorge, as a counterpoint to the justified opposition to clunker schemes like the casino and Nestle plant that would harm the Gorge.

CLIMB West

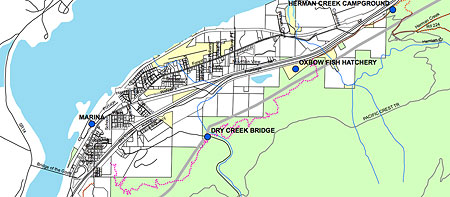

The Cascade Locks proposal begins with a new trail traversing above the community from a western trailhead near the Bridge of the Gods to an eastern terminus at the Oxbow Fish Hatchery (where Nestle proposes to bottle the natural springs by the semi-truck load).

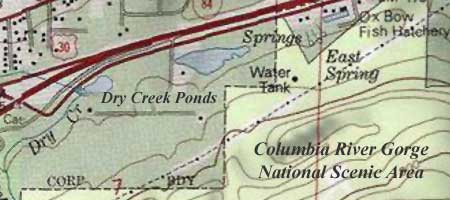

Along the way, the proposed trail would cross Dry Creek, intersecting the primitive access road that follows the creek upstream to beautiful Dry Creek Falls.

Curiously, the proposal does not incorporate this old road into the mountain bike network — a missed opportunity to close the route to ATVs and motorcycles that routinely use the road to loop onto the Pacific Crest Trail. Cyclists would likely find their way to the falls, of course, but including this road segment in the system would be a great way to transition the route (and surrounding area) to quiet recreation.

Another missing link in the western portion of the network is from the Oxbow Fish Hatchery to Herman Creek. While the terrain here is challenging, making this connection on trails — as opposed to following the freeway frontage road, as shown in the draft plan — could be critical to the viability of the network as a system based in Cascade Locks. The goal for the project should be for cyclists to start and end their tour in Cascade Locks, not at trailheads located east of town along forest roads (though that would certainly occur, as well).

Hopefully, the plan can at least include a long-term concept for making a new trail connection across Herman Creek to fully integrate the trail system with the town of Cascade Locks.

CLIMB East

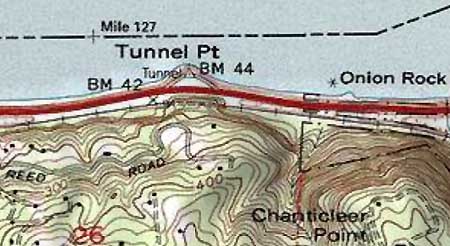

Most of the proposed CLIMB network is located along the corridor between Herman Creek and Wyeth, with a combination of new trails and existing routes that would create a number of loops and interesting destinations, with trail access at several points along the way.

This part of the proposal envisions using Trail 400 and a short segment of the Herman Creek Trail as part of the network, a move that hikers might be leery of, but one that is highly workable and necessary to create trail loops. Trail 400 is gently graded and meticulously maintained, so is a good candidate for shared use. The segment of the Herman Creek Trail included in the proposal is really just an old road, so can easily accommodate the additional traffic and mix of bikes and hikers.

The eastern trail proposal would be anchored by the Herman Creek and Wyeth Campgrounds. While a plus for cyclists looking for a camping/cycling experience, this underscores the need for a direct trail connection from Herman Creek to Cascade Locks, and the potential economic benefit it would bring, including bike campers riding to town for a meal, beer or supplies.

The Historic Columbia River Highway (HCRH) restoration project is considering adding the Herman Creek to Wyeth roadway to the historic highway corridor, a move that would provide a terrific complement to the mountain bike trail concept. Already, this road provides excellent opportunities for small trailheads accessing the proposed system, allowing for more route possibilities for cyclists and shuttles.

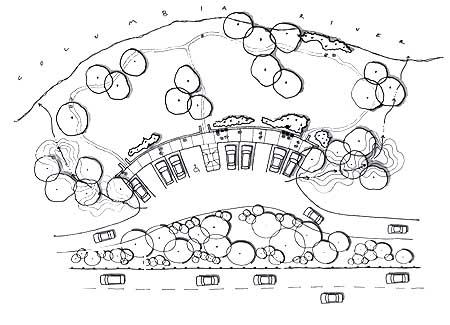

One missed opportunity in the eastern part of the proposal that could be both bold and iconic would be repurposing the Forest Service work center at Herman Creek to function as a trailhead base for cyclists. This historic structure dates back to the Civilian Conservation Corps era, but has been relegated to administrative uses by the Forest Service. The CLIMB proposal could turn this structure into a flagship facility for cyclists, possibility with a public-private lodge function patterned after the lodges at Timberline and Multnomah Falls.

The old work center also features a nearly lost trail connection that switchbacks directly to the Herman Creek Campground (and shown on the CLIMB trail concept), providing a nice complement for cyclists camping in the area if the work center were to become some sort of base facility.

Thinking bit further outside the box, another opportunity could be to add the old quarry site at nearby Government Cove to the proposed trail network.

The quarry is on a peninsula that separates the Columbia River from the cove, and has the potential to be a terrific riding destination, especially for riders following street routes from Cascade Locks to the Herman Creek trailhead. It would also bring the CLIMB network to the river, which is currently a missing piece in the proposal. The property appears to be port-owned, so could be a natural fit, given the port’s role in advocating for the project.

Project Timeline

Since the project began in 2007, a feasibility study, conceptual trail plan and master trail plan have already been completed with funding support from the Port of Cascade Locks, City of Cascade Locks, and Hood River County.

The next step is to conduct an environmental review of the trail corridor. In late 2010, the Port of Cascade Locks reached an agreement with the U.S. Forest Service to perform the required National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) analysis of the proposal using private consultants, since the Forest Service lacked the capacity to do this work in the near future. Several proposals to complete the work were received earlier this year, but at a cost of $170,000 to almost $400,000, were financially out of reach for the Port of Cascade Locks.

The Port and the USFS have since worked out a tentative agreement to allow this project to continue to move forward using limited Port funding to begin gathering environmental data, with the Forest Service taking over the environmental analysis in 2013, using this data.

Learn More & How to Help

For more information on the proposal, including more detailed maps, visit to the Port of Cascade Locks site here. You can also view photos of the proposed trail routes and promote the idea using the project’s Facebook link. Someday, we may have a world-class mountain bike network defining the economy in Cascade Locks, who knows?

But in the meantime, the best way to keep casinos and Nestle trucks from tainting the Gorge is to vote with your wallet, and simply to support local businesses in the Gorge that rely on tourism. If you traditionally stop somewhere in the Portland area for a beer or burger after a hike or trail ride, consider a stop in Cascade Locks, Stevenson or Hood River, instead.