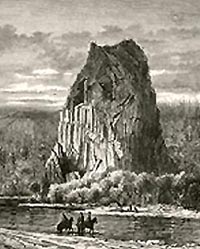

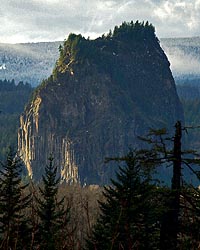

Beacon Rock rising above the Columbia, as viewed from the Oregon side

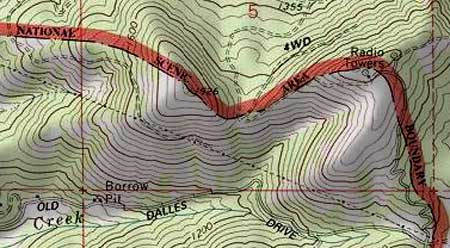

Beacon Rock rises nearly 1,000 feet above the Columbia River, and forms the nucleus of some of the finest park lands on the Washington side of the Columbia Gorge. The famous network of catwalks and stairways installed on Beacon Rock in the 1920s leads thousands of visitors to the airy summit each year to marvel at the view.

Nineteenth-century engraving of an early Beacon Rock scene

Beacon Rock, itself, is a testament to conservation, having been saved from an early 1900s scheme to actually mine the monolith for quarry stone. Today, it is among the most visited — and best loved — spots in the Gorge, with campgrounds, picnic areas and an impressive network of hiking and bicycling trails. But when the park boundaries were laid out for Beacon Rock, the Oregon side of the river was left out of the equation.

In the early days of white settlement, fish wheels operated in the shadow of Beacon Rock, along this section of the Oregon shore, harvesting salmon from the vast migrations that moved up the river.

Early settler Frank Warren operated a cannery on the site, and the town that grew around his operation became known as Warrendale. (editor’s note: Frank Warren was the only Oregon resident known to have perished on the Titanic; his wife Anna was among the few to escape in a lifeboat, and survived, while her husband stayed behind on the ship to help other women and children into lifeboats)

Present-day view of Beacon Rock from the Oregon side

After the demise of fish wheels and the Warren cannery in the early 1900s, Warrendale began a slow slide into obscurity. Today, the former town site has largely been replaced by Interstate-84, and a dozen homes now occupy this remnant of private parcels along the Columbia River.

This is where the story gets a bit ugly. Like all inholdings in the Gorge and around Mount Hood, the river front homes in Warrendale suffer from trespassing — both by well-meaning visitors simply trying to find access to the river, and by less courteous visitors who clearly don’t respect the numerous private property postings.

The lure of the river here is undeniable. Beacon Rock towers across the Columbia, and sandy beaches line the river in summer and fall. Yet, no public access exists along this stretch of Oregon shoreline, and thus the tension between land owners and visitors.

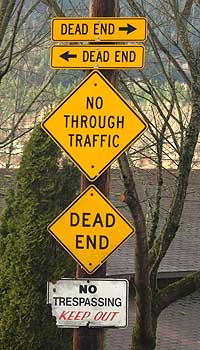

Tensions run high in Warrendale as property owners struggle to block visitors from trespassing to reach Columbia River beaches

Some landowners have taken drastic steps, in response, posting profane signs that have shocked more than a few families who have stumbled into Warrendale. Less confrontational signs show up everywhere, making it abundantly clear that the public is not welcome in this community.

Even the official signposts in Warrendale bear blunt warnings for visitors

There’s no doubt that the view from these homes is among the most spectacular anywhere, but in the long term, should this stretch of beach be reserved for just a few? After all, were it not for the fish wheel and cannery that once stood here, this would likely be public land, with public access for all. Is it possible that in the long term, this unique spot can be dedicated to public access?

Not in the near term, in all likelihood. Though the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area (CRGNSA) receives funds each year from Congress for the express purpose of acquiring private parcels in critical locations, most acquisitions are for properties that directly abut federal or state lands, or are in pristine condition. The dozen homes in Warrendale are neither — they are separated from public lands by Interstate-84 and largely developed.

One viable option for the CRGNSA is to follow the lead of private land acquisition organizations, like the Nature Conservancy and Trust for Public Lands, and purchase conservation easements or living trusts for these properties. For private conservation groups, these have been valuable real estate tools for eventually bringing private lands into the public realm. Another option is a partnership between the CRGNSA and one of these organizations to reach a similar result.

It’s not too soon for the CRGNSA to be thinking about this possibility. This is a million dollar view that deserves to be enjoyed by all, not just a few.

Postscript: In June 2010, one of the riverfront homeowners in Warrendale, 68-year-old James Koch, threatened four salmon fishermen who were anchored for the night in their boat just offshore, then fired rifle shots toward the boat. After his arrest by Multnomah County authorities, he was found guilty of felony unlawful use of a weapon, misdemeanor menacing and misdemeanor recklessly endangering other.

During his trial, he called on neighbors who testified about the public encroaching on their riverfront property. In this November 3, 2010 Oregonian article, one of the fishermen, Steve Bruce, said he was “sickened by that attitude. It’s not just him (Koch), they all feel that they own the land under the water.”

Koch could face prison time, pending sentencing, and will lose is right to own or operate firearms.

Second Postscript: In November 2010, James Ellis Koch was sentenced in Multnomah County court to 60 days jail time and three years probation for firing weapons at four salmon fishermen who were anchored for the night in their boat just offshore from his Warrendale property.

In this November 19, 2010 Oregonian article, Judge Janice Wilson took issue not only with Koch’s unrepentant attitude, but also with the vigilante culture that exists in the Warrendale community. From the article:

James Koch also offered these words: “I’m sorry for whatever happened, the stuff that happened out there that evening.”

That prompted this response from the judge. “(That) is not an apology,” she said. “It’s actually worse than nothing. It’s an anti-apology.”

The judge said Koch wasn’t justified that night in the slightest. The fishermen weren’t making noise, they weren’t drinking and they were lawfully camping on the water. The judge said she was concerned about Koch’s attitude, as well as the attitudes of his neighbors.

Neighbors testified that they are so wary of strangers and crime that they stop unknown drivers traveling through their remote east county hamlet. Yet on the night Koch fired his weapons, they didn’t look to see what was going on because shots in their neighborhood aren’t unusual.

“I don’t know what that says about that neighborhood … but it’s a little bit scary,” the judge said. “… This vigilante culture in this neighborhood is of grave concern to the court.