The age of the microprocessor has ushered in a revolution in the fields of cartography and geosciences. After all, few could have imagined streaming Google Earth imagery over a worldwide web when the first air photos were being scanned and digitized in the 1980s.

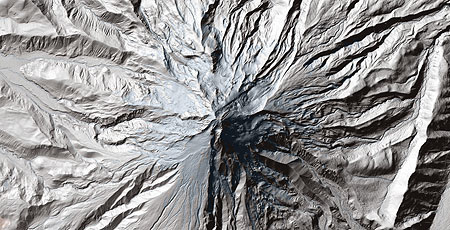

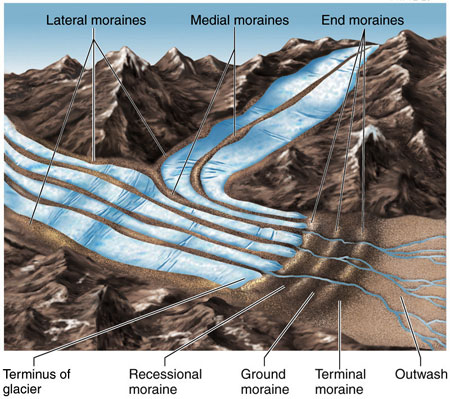

The latest innovation on the geo-data front promises still more detailed geographic information than has ever been available before: Lidar (light detection and ranging) is a new technology that uses aircraft-mounted lasers to scan the earth at an astonishing level of detail. The resulting data can be processed to create truly mind-boggling terrain images that are rocking the earth sciences.

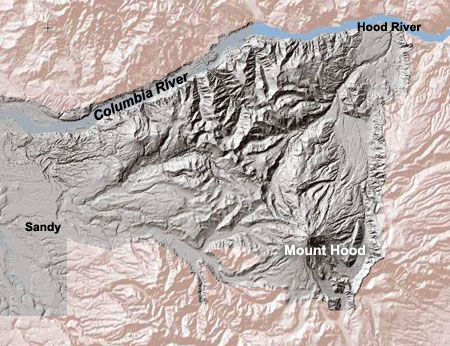

The Oregon Department of Geology & Mineral Industries (DOGAMI) has kicked off a project to develop a statewide lidar database. The effort began with a pilot project in the Portland metropolitan region in 2006, expanding to become a statewide effort in late 2007. Some of the first available imagery encompasses the Mount Hood region, including the Columbia River Gorge. The following map shows DOGAMI’s progress in lidar coverage (in gray) as of 2011:

A New Way to See Terrain

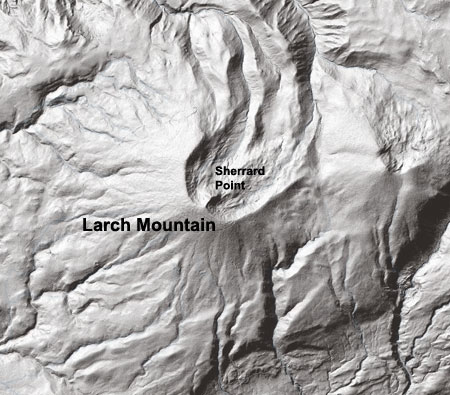

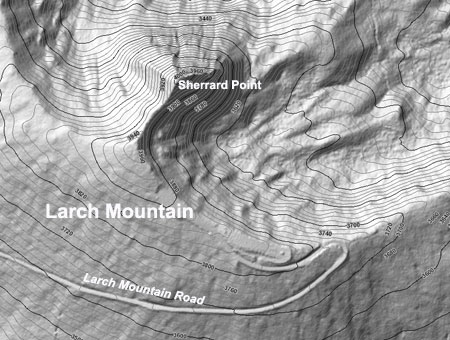

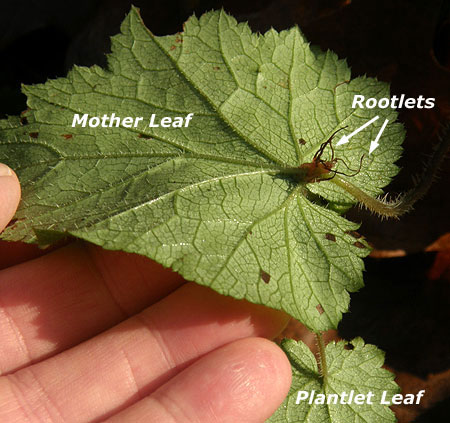

Lidar imagery has a “lunar” look, thanks to its tremendous detail and the ability for lidar new technology to “see through” forest vegetation. This view of Larch Mountain, for example, immediately reveals the peak to be the volcanic cone that it is, complete with a blown-out crater that was carved open by ice-age glaciers:

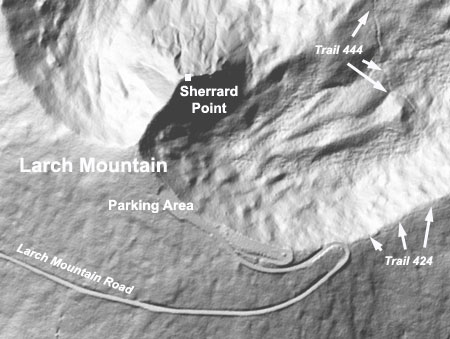

Move closer to the Larch Mountain view, and even more detail emerges from the lidar imagery. In the following close-up view, details of the Larch Mountain Road and parking area can be seen, as well as some of the hiking trails in the area:

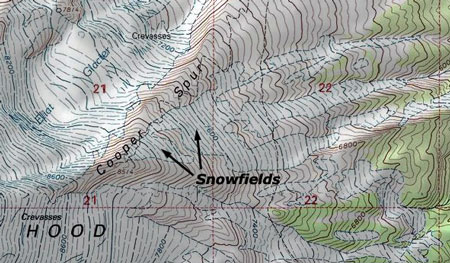

The Oregon lidar imagery includes elevation contour data, and for hikers and explorers using the new information to plan outings, this is probably an essential layer to include. Here is the previous close-up image of Larch Mountain with elevation data shown:

The contours are not simply a rehash of USFS ground-survey data, but instead, derived from the lidar scans. In this way, the contours are as direct a reflection of the lidar data as the shaded relief that gives the images their 3-D drama.

There are some caveats to the new lidar technology: while it is possible to see most roads and even some trails in great detail, in many areas, lidar doesn’t pick up these features at all. Lidar also edits most vegetation out of the scene, though the state does provide topographic overlays for vegetation.

DOGAMI is now streaming the lidar data over its Lidar Data Viewer website, finally putting the new imagery in the eager hands of the general public. For this article, I’ll focus on the highlights of my first “tour” of the Mount Hood and Columbia River Gorge areas covered by the project so far — a familiar landscape viewed through the “new eyes” of lidar.

Seeing the Landscape with “New Eyes”

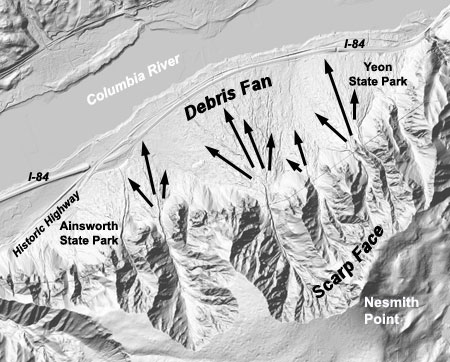

The first stop on the lidar tour is the Nesmith Point scarp face, a towering wall of cliffs that rise nearly 4,000 feet above Ainsworth State Park, near the rural district of Dodson. The Nesmith fault scarp has always been difficult to interpret from USGS topgraphic maps, with a maze of confusing contour lines that do little to explain the landscape. Air photos are even less helpful, with the steep, north-facing slopes proving nearly impossible to capture with conventional photography.

The lidar coverage of the Nesmith scarp (above) reveals the origin of the formation: a massive collapse of the former Nesmith volcano into the Columbia River, probably triggered by the Bretz Floods during the last ice age.

The Nesmith scarp continues to be one of the most unstable places in the Gorge. Over the millennia, countless debris flows have rushed down the slopes toward the Columbia, forming a broad alluvial fan of layered debris where traffic rushes along I-84 today. In February 1996, the most recent in this ancient history of debris flows poured down the canyons and across the alluvial fan, destroying homes and closing both I-84 and the railroad for several days.

Lidar provides a new tool for monitoring unstable terrain like the Nesmith scarp, and may help in preventing future loss of life and public infrastructure when natural hazards can be more fully understood.

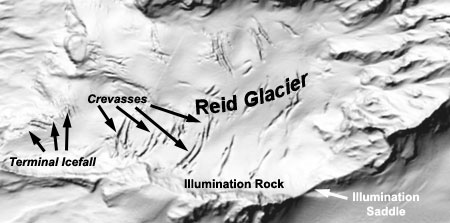

The ability to track detailed topographic changes over time with lidar is the focus of the next stop on the lidar tour: the Reid Glacier on Mount Hood’s rugged west face. As shown in the lidar image, above, bands of crevasses along the Reid Glacier show up prominently, and for the first time this new technology will allow scientists to monitor very detailed movements of our glaciers.

This new capability could not have come at a better time as we search for answers in the effort to respond to global climate change. In the future, annual lidar scans may allow geologists and climate scientists to monitor and animate glaciers in a way never possible before.

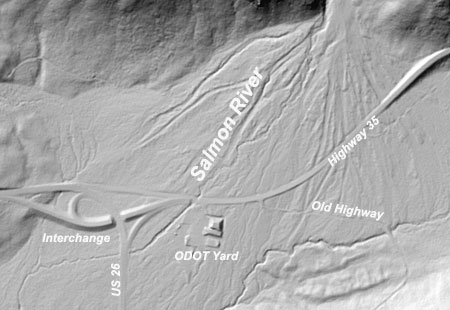

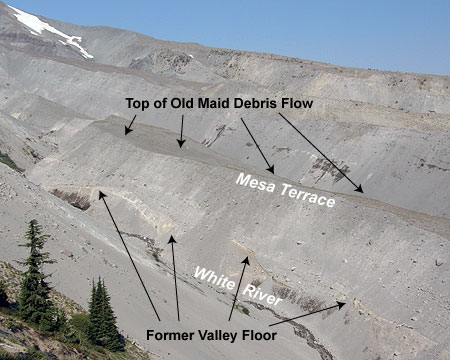

Moving to Mount Hood’s south slopes on the lidar tour, this image shows the junction of US 26 and Highway 35, which also happens to be built on the alluvial fan formed by the Salmon River, just below its steep upper canyon.

Unlike the nearby White River, the Salmon has had relatively few flood events in recent history. To the traveling public, this spot is simply a flat, forested valley along the loop highway. Yet, the lidar image shows dozens of flood channels formed by the Salmon River over the centuries, suggesting that the river has temporarily stabilized in its current channel — but not for long.

DOGAMI geologists are already examining the lidar imagery for these clues to “sleeping” calamities: ancient landslides, fault lines and flood zones concealed by a temporary carpet of our ever-advancing forests.

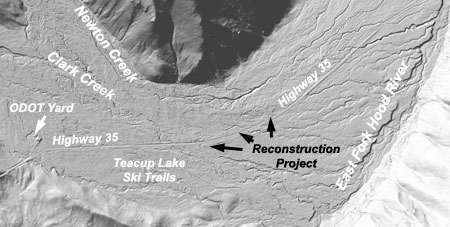

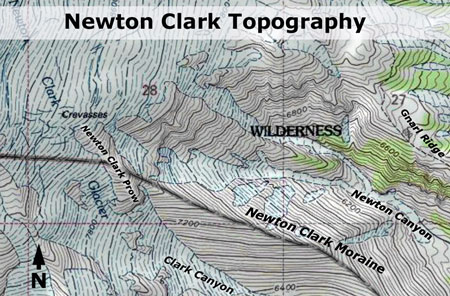

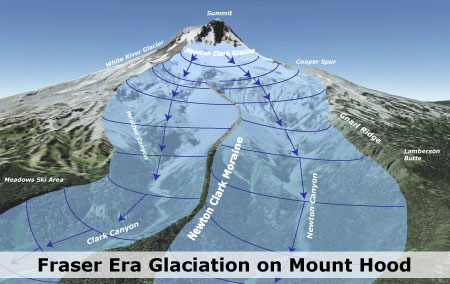

The lidar images reveal a similar maze of flood channels at our next stop, where glacial Newton and Clark creeks join to form the East Fork Hood River. This spot is a known flood risk, as Highway 35 is currently undergoing a major reconstruction effort where debris flows destroyed much of the highway in November 2006.

While the highway engineers are confident the new highway grade will hold up to future flood events, the above lidar image tells another story: with dozens of flood channels crossing the Highway 35 grade, it seems that no highway will be immune to floods and debris flows in this valley.

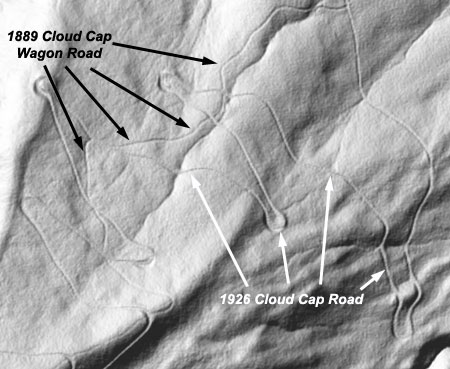

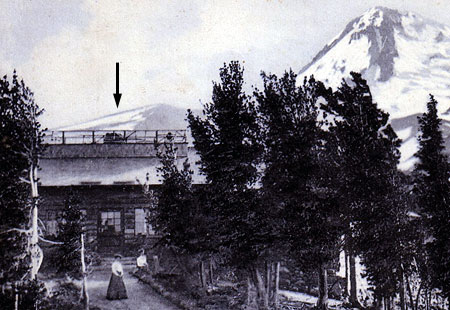

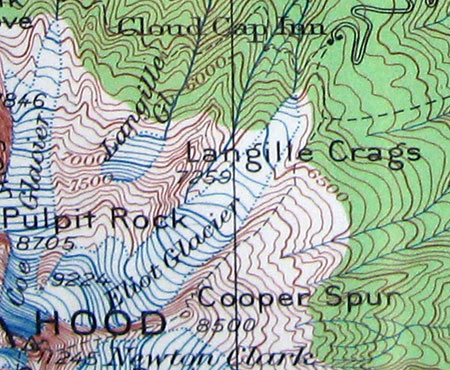

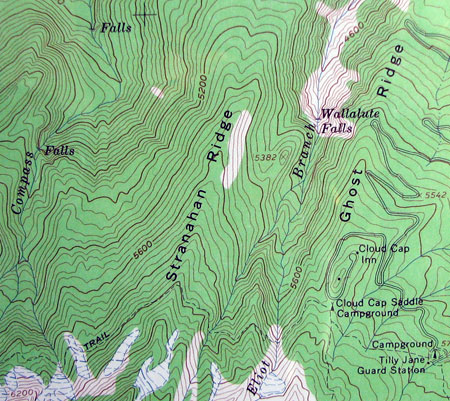

The new lidar images also provide an excellent tool for historical research. The following clip from below Cloud Cap Inn on Mount Hood’s north side is a good example, with the lidar image clearly showing the “new”, gently graded 1926 road to Cloud Cap criss-crossing the very steep 1889 wagon (or “stage”) road it replaced:

The Cloud Cap example not only highlights the value of lidar in pinpointing historic features, but also in archiving them. In 2008, the Gnarl Fire swept across the east slopes of Mount Hood, leaving most of the Cloud Cap grade completely burned. Thus, over time, erosion of the exposed mountain slopes may erase the remaining traces of the 1889 wagon road, but lidar images will ensure that historians will always know the exact location of the original roads in the area.

Moving north to the Hood River Valley, the value of lidar in uncovering geologic secrets is apparent at Booth Hill. This is a spot familiar to travelers as the grade between the upper and lower Hood River valleys. Booth Hill is an unassuming ridge of forested buttes that helps form the divide. But lidar reveals the volcanic origins of Booth Hill by highlighting a hidden crater (below) that is too subtle to be seen on topographic maps — yet jumps off the lidar image:

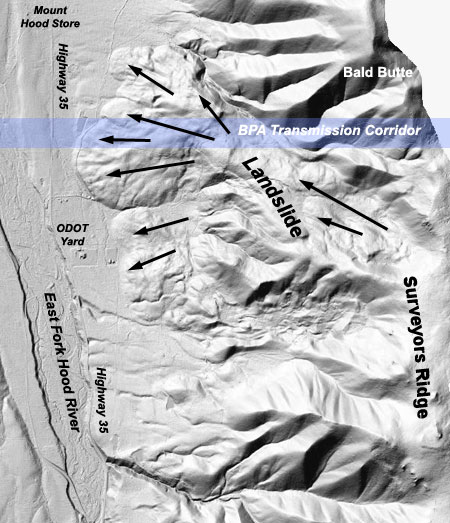

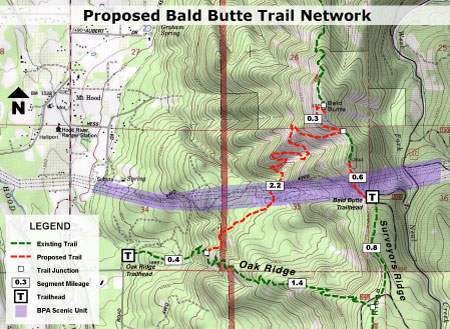

Another, nearby geologic secret is revealed a few miles to the south, near the Mount Hood Store. Here, an enormous landslide originates from Surveyors Ridge, just south of Bald Butte, and encompasses at least three square miles of jumbled terrain (below):

Still more compelling (or perhaps foreboding) is the fact that the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) chose this spot to build the transmission corridor that links The Dalles Dam to the Willamette Valley. The lidar image shows a total of 36 BPA transmission towers built on the landslide, beginning at the upper scarp and ending at the toe of the landslide, where a substation is located.

As with most of the BPA corridor, the slopes under the transmission lines have been stripped of trees, and gouged with jeep tracks for powerline access. Could these impacts on the slide reactivate it? Lidar will at least help public land agencies identify potential natural hazards, and plan for contingencies in the event of a disaster.

Mount Hood Geologic Guide and Recreation Map

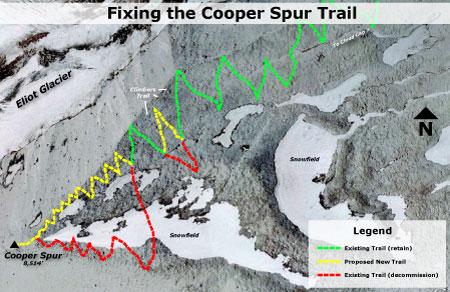

You can tour the lidar data on DOGAMI’s Lidar Data Viewer, but for portability, you can’t beat the new lidar-based recreation map created by DOGAMI’s Tracy Pollock. The new map unfolds to 18×36”, and is printed on water-resistant paper for convenient use in the field.

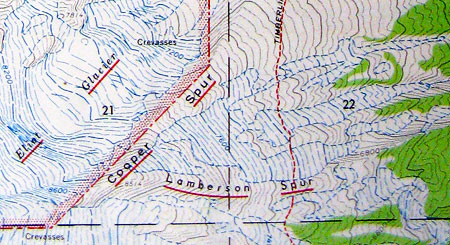

Side A of the new map focuses on the geology of Mount Hood, with a close-up view of the mountain and most of the Timberline Trail:

(click here for a larger version)

Side B of the map has a broader coverage, and focuses on recreation. Most hiking trails and forest roads are shown, as well as the recent Mount Hood area wilderness additions signed into law in 2009:

(click here for a larger version)

You can order printed copies of this new map for the modest price of $6.00 from the DOGAMI website, or pick it up at DOGAMI offices. It’s a great way to rediscover familiar terrain through the new lens of lidar.