Aerial view taken last fall of the scorched aftermath of the 2025 Burdoin fire (Wikimedia)

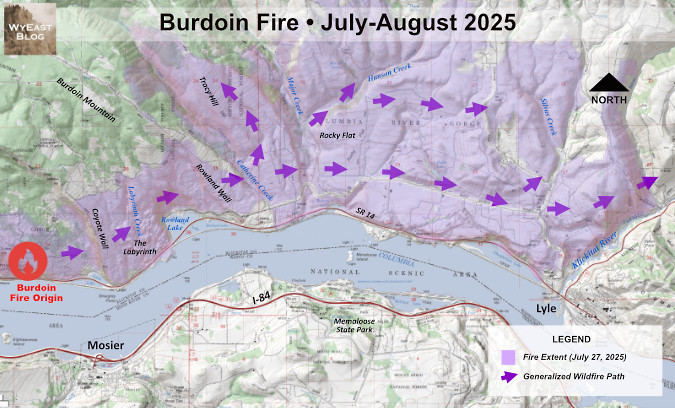

The Burdoin Fire erupted east of White Salmon in late July last year, burning across some of the most popular recreation lands in the East Gorge. The fire began along State Route 14 and quickly spread eastward, and by the time it was controlled in mid-August, it had burned a swath nearly 10 miles long and blackened more than 11,000 acres. More than 100 structures were lost in the fire, though no lives were reported lost.

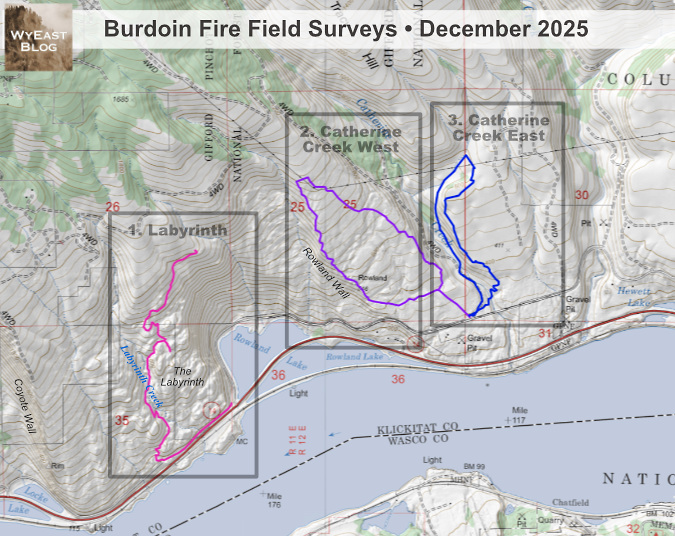

This is the second article in a 3-part series that provide a virtual tour of the aftermath of the fire on public land ecosystems across three separate areas. Each article is centered on popular trail, each with a different story to tell. The photos for this series are from mid-December 2025, when winter rains had already begun to rejuvenate the wildflower grasslands. Part 1 of the series can be found here.

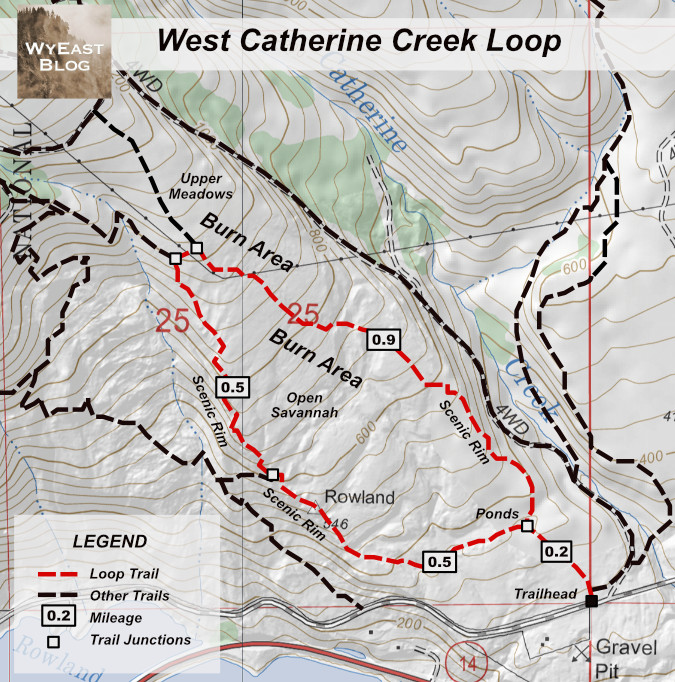

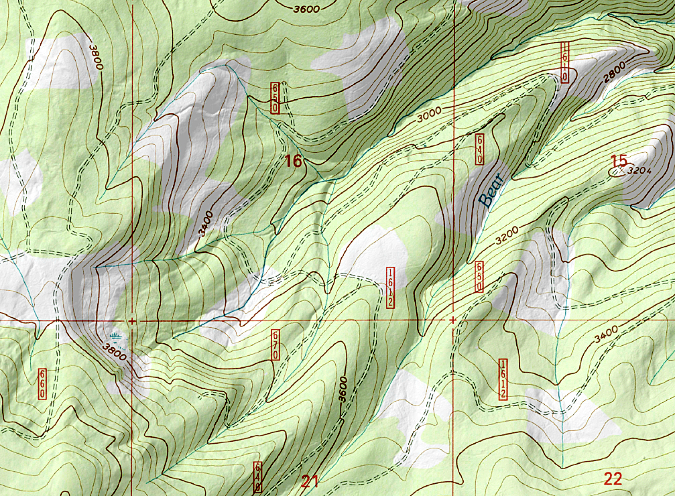

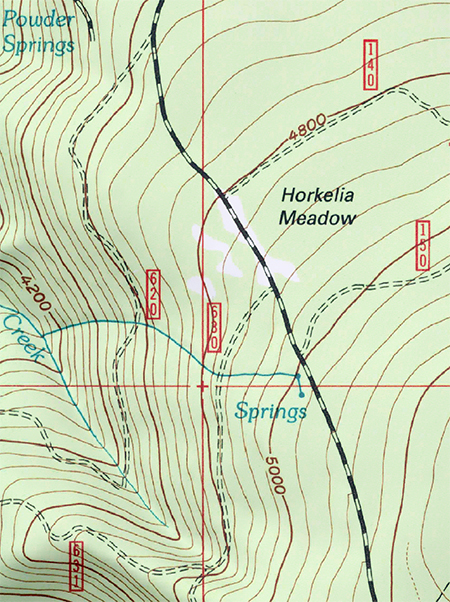

This second installment examines the central part of the fire, where it burned across the section known Rowland Wall and the meadows of the West Catherine Creek savannah (shown as subarea 2, below). This subarea is defined by the popular Rowland Wall-Bitterroot trail loop, shown in purple on the map.

This section of the Burdoin Fire is unique from the rest of the burn, as it was the second major fire to burn through this in less than a year. The impacts of the previous burn, known as the Top of the World Fire, are described in this 2025 WyEast Blog article.

When documenting the landscape for the 2025 article, it didn’t occur to me that the area could burn again, so soon, as there wasn’t much fuel left from the previous fire. With fire as a natural and essential part of the dry savannah ecosystem, we’re somewhat conditioned to think the burn cycles have some degree of order to them, only sweeping through occasionally, when they can be beneficial in rejuvenating the landscape.

Not so for the West Catherine Creek area, however. For many of the groves of Oregon white oak and Ponderosa pine that are keystone species in this subarea, the Burdoin Fire proved too much, too soon. Only a few trees that survived the first fire seem to have survived the second burn, though we won’t know the full impact until this spring – and beyond.

Catherine Creek West: A Cautionary Story of Fragility

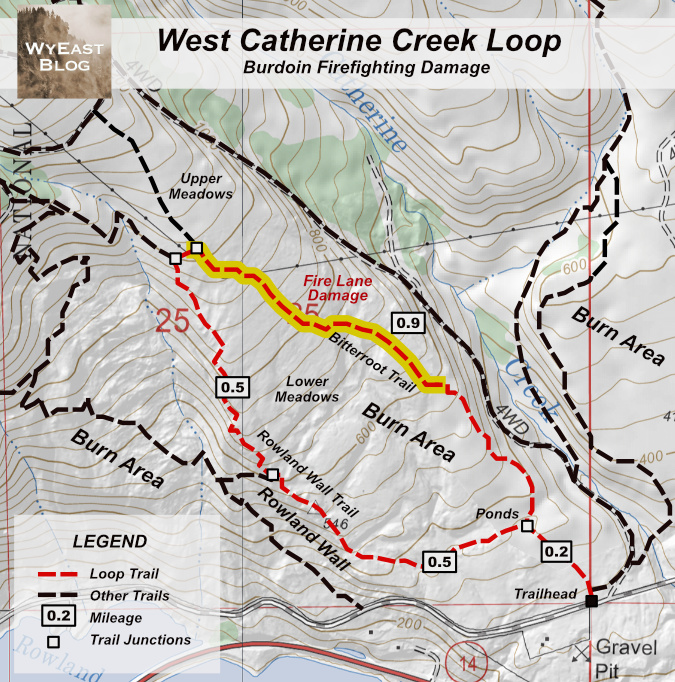

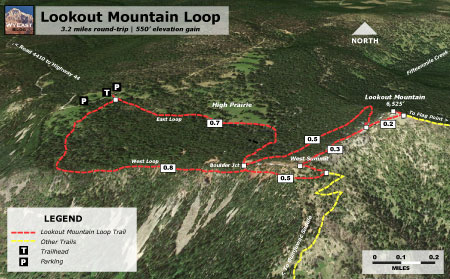

The popular trail that follows the exposed basalt rim of Rowland Wall is how most people visit the meadows west of Catherine Creek, often following a loop that includes the Bitterroot Trail that follows the west rim of Catherine Creek, about a mile east of Rowland Wall. While there are Forest Service plans to someday formalize some of these routes, the unofficial user trails people know today are rocky, winding ascents through Missoula flood-scoured terrain. The two trails eventually climb just above the reach of the ice age floods, connecting where they cross sweeping wildflower meadows and grasslands.

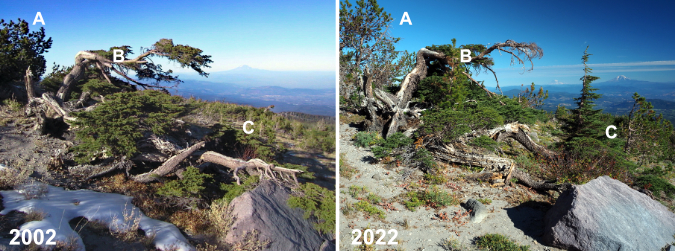

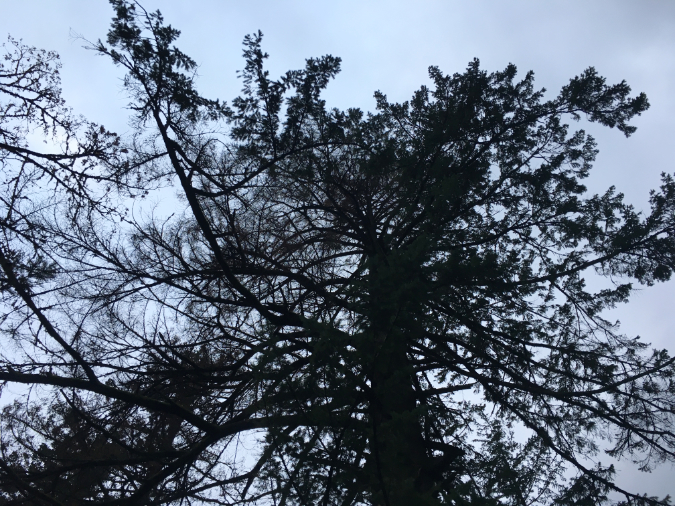

Trees are scarce along the Rowland Wall, limited to just a few gnarled oak and pine krummholz clinging to the basalt. Move away from the exposed rim and groves of oak and pine are scattered across the meadows in a textbook example of the oak savannah ecosystem.

Oak savannah landscape of West Catherine Creek in spring 2025, bouncing back after the September 2024 fire had burned through the area.

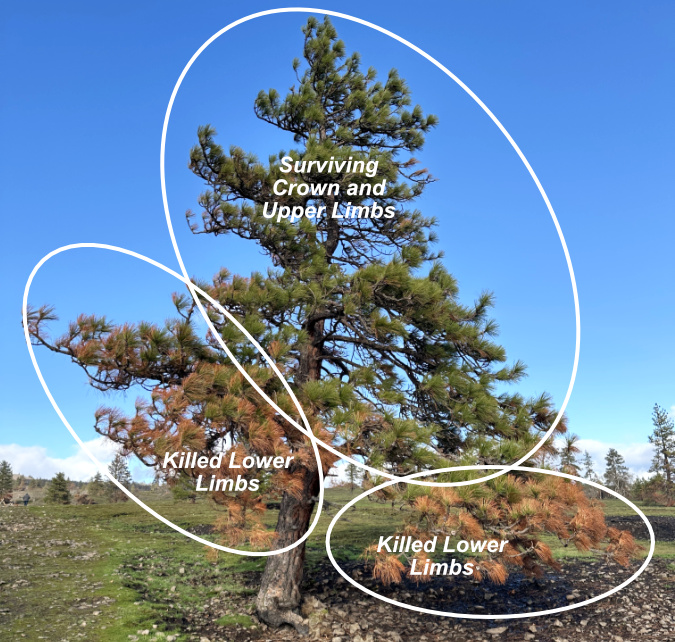

As described in the previous article on the Top of the World Fire recovery, the burned portions of western Catherine Creek bounced back strongly last winter and spring, just months after the fire. If measured by the buildup of woody debris and heavy brush among the groves of oak and pine, that fire was overdue. Some trees were killed by the 2024 fire, though most of the Ponderosa pine survived, often improving their fire-readiness by shedding scorched, lower limbs that risk serving as a “ladder” to a fatal crown fire in future burns.

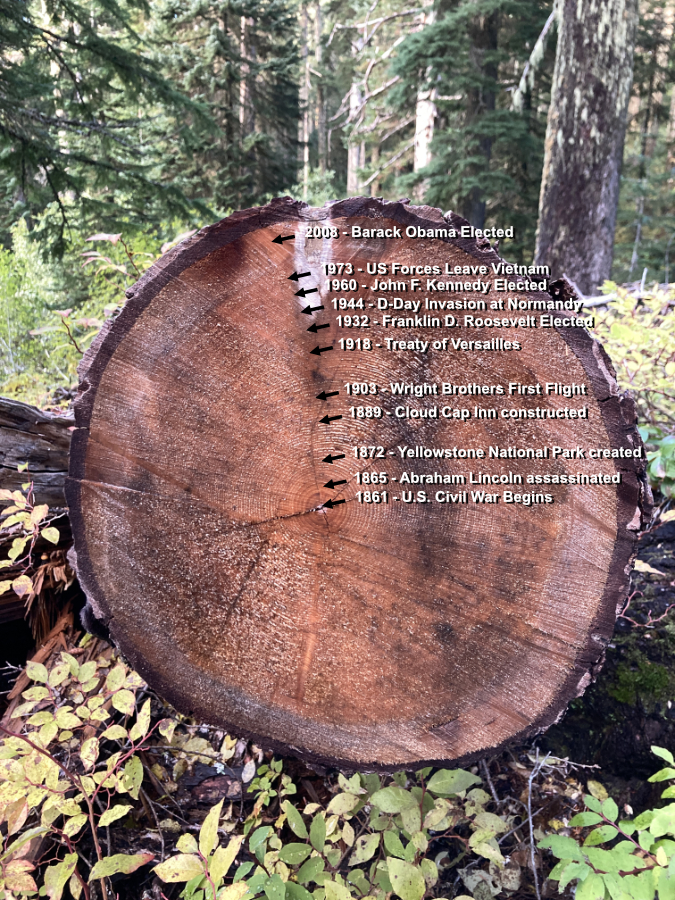

The Burdoin Fire was that fire, and it simply came too soon. Along with their thick, jigsaw-puzzled bark, shedding low-hanging canopy is a literal trial-by-fire adaption of Ponderosa pine to a fire forest ecosystem, with ancient survivors carrying their foliage high above their thickly barked trunks. The Burdoin Fire granted no such time for the survivors of the 2024 fire to adapt.

These back-to-back fires at West Catherine Creek underscore a challenging reality in coping with fire in an era of changing climate and a long history of fire suppression: while our east side forests and savannahs require fire for their health, fires that burn too hot or too frequently can also set forest recovery back by decades. As resilient as they have evolved to be, the dry east side ecosystem can be equally fragile when stressed beyond the point of recovery.

The Oaks

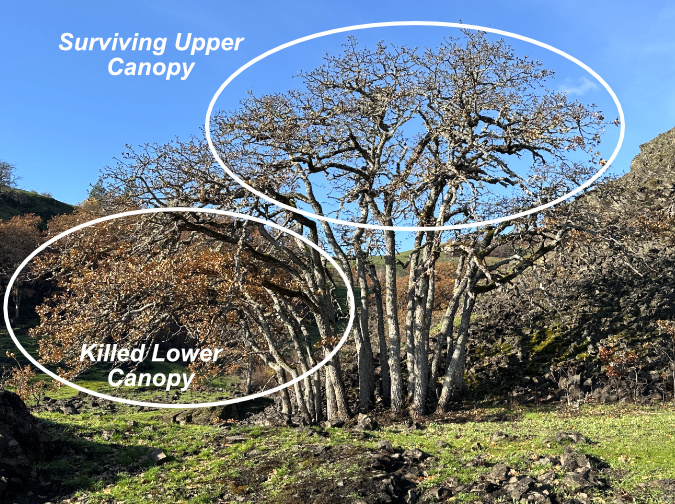

While the keystone Oregon white oak groves along the Labyrinth Trail (in the first installment to this series) had already begun to recover over the fall months, the oaks in the West Catherine Creek area fared poorly, most having already endured the Top of the World fire. Few were showing any sign of rebound since the Burdoin as of December, though we won’t know until spring foliage emerges in late April just how impacted these trees are.

Like those in the Labyrinth, the oaks west of Catherine Creek that burned still held many of their dead leaves into December, as their normal autumn leaf-drop cycle was interrupted on limbs killed in the fire.

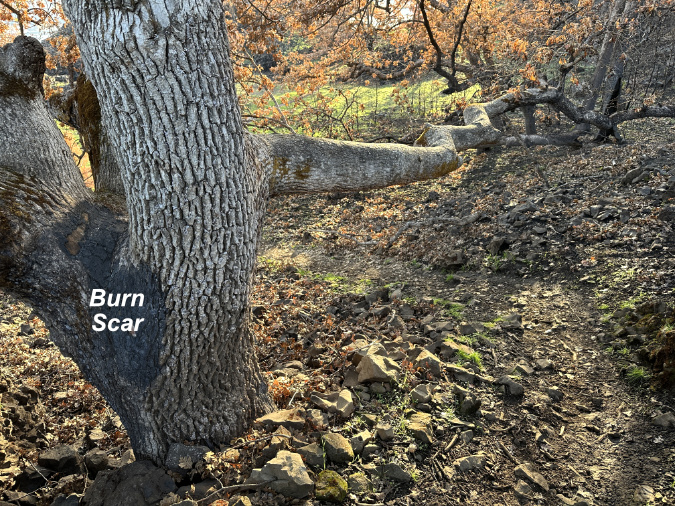

This venerable oak on the west edge of Catherine Creek canyon was hit hard by the Burdoin Fire, like so many of the oaks in this part of the burn.

The burn scars on the trunk of this tree tell the story: the fire burned hot on the right side of the tree, enough to kill the bark and most of the tree’s foliage.

The fire burned hot enough to completely blacken the leaves on the lower limbs of this tree. We won’t know until spring if trees like these somehow survived the fire.

Unlike the nearby Labyrinth area, few oaks showed new growth since the fire – this tree was among the few in the West Catherine Creek area to push up new shoots from its surviving roots over the summer and fall.

This oak along the west Catherine Creek rim has a good chance of surviving the fire. Browned foliage marks the parts that were likely killed by the fire, but the bare upper canopy is a sign that at least part of the tree survived long enough to drop its leaves normally in fall.

Though the oaks in the west Catherine Creek area did not show the almost immediate signs of recovery seen in The Labyrinth, some of the badly burned oaks here will still likely produce new growth from their surviving roots. For the burned oaks that don’t bounce back in spring, their long-term replacement will depend on acorns carried in from a few unburned trees scattered along the rim of Catherine Creek canyon and other surviving groves along the fire’s perimeter.

For us, this could mean decades before we will see mature oaks again in the most intensely burned part of the Burdoin fire. For the oak trees, this is an expected, cyclical event in their ecosystem they have evolved to rely upon, and a recovery process they have repeated time and again over the millennia.

Scattered oak ancients along the west Catherine Creek rim completely dodge the fire. These trees will become the parents to new groves when their acorns help reseed nearby burned areas.

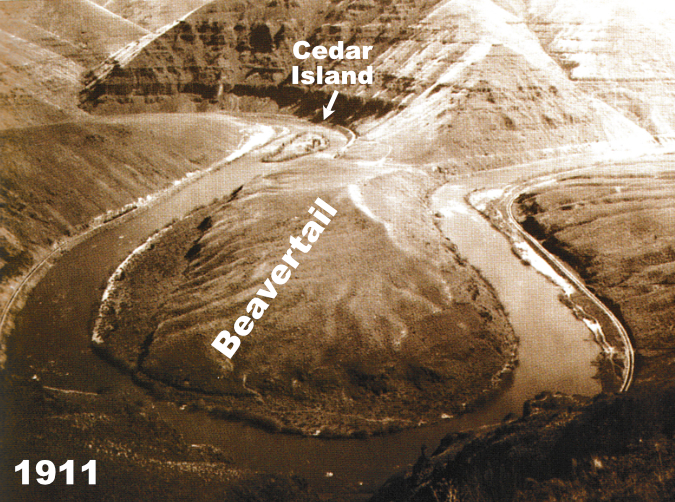

At first glance, this oak grove seems to have survived the fire. But it isn’t a grove at all…

…as a closer look reveals this to be a multi-trunked, single oak tree….

…and a still-closer look reveals a hole at the center that marks this as a tree that rebuilt itself from surviving roots decades ago with the original trunk – now gone — was likely killed in a wildfire. This tree is living example of how our Oregon white oak have completely adapted to fire as an essential part of their ecosystem, periodically rejuvenating the landscape.

The Pines

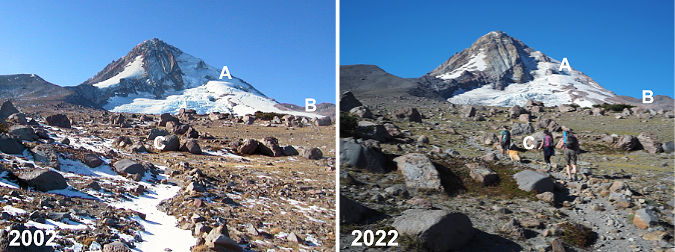

If the Ponderosa pines in the West Catherine Creek area had been allowed a few years to shed lower canopy killed in the 2024 fire, the story might be different here — one of emerging, future giants becoming increasingly invulnerable to fire. Instead, the pines that survived the first fire at didn’t have time to shed killed limbs, which then became tinder-dry fuel for the flames to climb still more quickly into crown fires, killing many trees. Due to this effect, only a few Ponderosa survived in this part of the Burdoin burn. This is surprising, given that little understory or downed debris remained from the first fire to provide fuel to the second burn, suggesting the heat stress of a second fire, alone, was too much for many of these trees to survive.

Young Ponderosa and older, wind-stunted trees built low to the ground were the main victims in the second fire. Some of these trees had made it through the first fire having lost half or more of their canopy, yet surviving enough to add new foliage last spring. However, this left them weakened and vulnerable when the Burdoin Fire came through, and most surviving small or low trees were completely killed in this second round.

As described in this article, the rocky margins of Rowland Rim were spared in the 2024 fire, but burned in the second event, killing some of the most iconic “krummholz” trees in the area. However, the fire seemed to lose intensity as it reached the west rim of Catherine Creek canyon, and several of the iconic Ponderosa that burned in this area stand a chance of surviving. This could be due to the lack fuel from brush and dry debris that had already burned in the 2024 fire.

What will the Ponderosa groves look like in this area in the future? Some large trees seem likely to survive, ready to re-seed and rebuild burned groves until the next fire event sweeps through.

This sturdy Ponderosa was hit hard by the fire. Like most of the stunted pines in exposed areas, it wasn’t tall enough to escape the reach of the fire as typical Ponderosas of this age is adapted to do.

The deeply burned patch to the west of the old pine tells the larger story. This scar likely marks a downed tree, dense brush – or both – that burned long and hot enough to all but kill the old Ponderosa that was just downwind during the fire.

A handful of green limbs are still hanging on, giving this tree at least some chance of surviving, despite having already lost its crown prior to the fire – possibly from lightning. Still, the odds remain long for this old tree.

Some of the most intense burning at the West Catherine Creek savannah was along the lower slopes that didn’t burn in the 2024 fire. Here, the dense understory and buildup of debris burned hot enough to completely kill this mixed grove of Ponderosa pine and Oregon white oak.

The Burdoin Fire also killed this crowded stand of young Ponderosa on the lower slopes that was spared by the 2024 fire, crowning in several of the trees. Tough as this scene is to look at, Ponderosa in the East Gorge rely upon fire to prevent crowded stands and competing with overgrown underbrush.

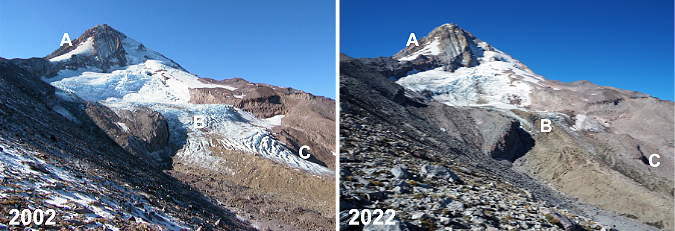

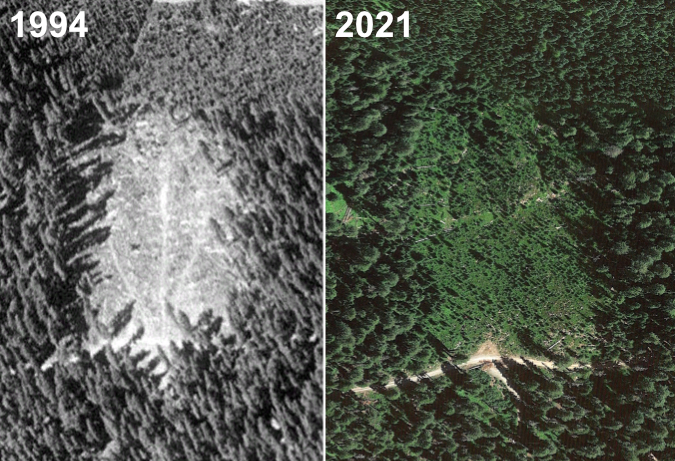

This grove of Ponderosas was hit hard by the 2024 fire due to a buildup of fallen logs and other dry debris, and tree canopies that extended to the ground. The pair of pines on the left survived the first fire, while the heat from the two fallen logs killed the tree on the right and appeared to have doomed its neighbor, at center. This photo is from just a month prior to the Burdoin Fire, showing the already tinder-dry grasslands last summer.

This view shows the same grove just six months later. The lack of remaining fuel on the ground left from the first fire seems to have helped the grove endure the Burdoin Fire. The large Ponderosa at center is still hanging on, though it lost much of its canopy in the two fires, and it will be slow to recover if it does survive. The pair on the left seem to have survived the second fire, though the smaller of these Ponderosas lost much more of its canopy to the second fire after surviving the 2024 fire largely intact.

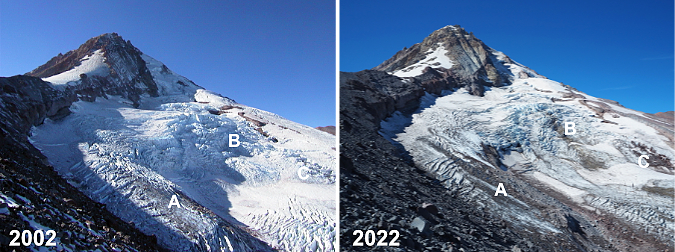

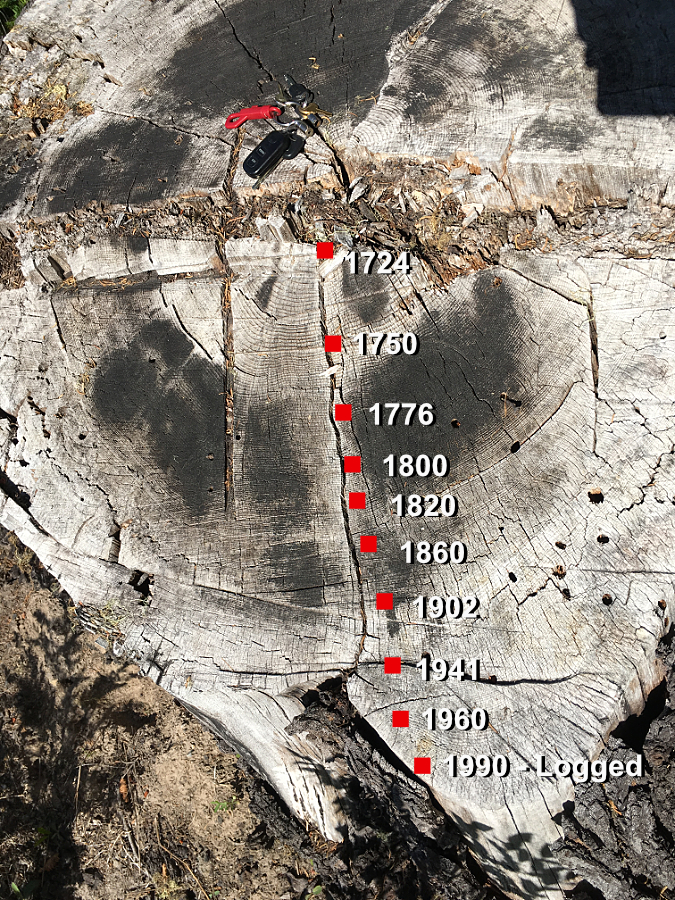

This Ponderosa had somehow escaped the flames during the 2024 Top of the World Fire, despite its low canopy and vulnerability to fire. Only a few limbs burned in the first fire…

…but the Burdoin Fire proved too much for this little tree. It was completely killed on the second fire…

…and the story of told through its charred bark. Though its trunk had been scorched in the first fire, the second fire proved too much, killing the tree’s living cambium layer beneath.

The story of this iconic Ponderosa (and its offspring) is in this previous blog post. It was among the many krummholz that were lost to the second fire to burn through the West Catherine Creek area in less than a year.

Looking west from Rowland Wall toward the Labyrinth, the scope of the fire comes into view. Surviving Ponderosa are green and easy to spot compared to browned pines killed by the fire. Oak groves with rusty-brown leaves still attaches are also likely killed by the fire, while groves with bare (gray in this view) branches likely survived – though we won’t know until spring.

Firefighting Scars

Until 1988, the public lands we know today as the Catherine Creek natural area were part of a private ranch called “Sunflower Hill”. The Forest Service began acquiring lands here as part of the creation of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area in 1988. The Friends of the Columbia Gorge, Columbia Land Trust and the Nature Conservancy have also been active in acquiring and restoring what had been heavily impacted private grazing land in the East Gorge, including at Catherine Creek.

While the Forest Service has since developed a few trails according to their master plan for Catherine Creek, most trails here are long-established user trails or old jeep tracks that date back to the ranching days. Such is the case for both the Rowland Wall and Bitterroot trails that form the loop described in this article. As user trails, they have no real status with the Forest Service, no matter how cherished or popular they may be with hikers. The Rowland Wall trail has some official standing for its proximity to a planned Forest Service trail that has yet to be built, but the Bitterroot Trail has no such status or protection.

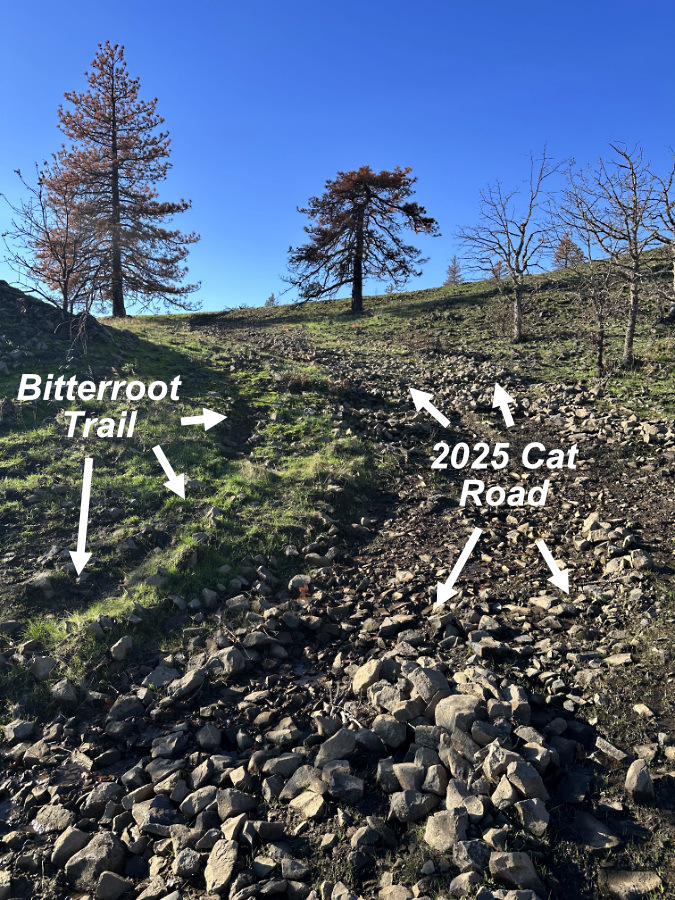

And thus, it was disheartening to discover that firefighters battling the Burdoin Fire last summer had transformed a half-mile section of the Bitterroot Trail into a bulldozed fire road – which, notably, failed to prevent the fire from burning eastward for several miles. Though federal laws require the Forest Service to restore trails impacted by firefighting, the Bitterroot Trail is simply an unofficial user path. Therefore, the Forest Service has no responsibility to retore the trail, despite its popularity and (formerly) excellent condition

However, the bulldozer road seems a clear candidate for restoration, as the Forest Service is obligated to decommission roads and bulldozer tracks created as part of fighting a wildland fire. Normally, this work would occur immediately after a fire event as part of the required Burned Area Emergency Responseprocess that is designed to prevent erosion and restore burned areas to their natural state. That said, we’re living in a time where the Forest Service capacity has been deeply compromised by the current administration, with environmental considerations being pushed aside in favor of increasing timber harvests and selling off mineral rights.

As of mid-December, when I last walked this section of trail, it was still in the shape left by the firefighters: a 15 to 20-foot scar across the open meadows of West Catherine Creek. Deep ruts left by the bulldozers were already channeling winter runoff and causing rill erosion, eroding the thin savannah soils this area was intended to protect when it was acquired by the Forest Service. Piles of rubble dredged up in the roadbuilding line the route, amplifying erosion by channeling runoff directly in the fall line of the slope.

An unwelcome legacy from the Burdon Fire: a haphazard cat road built by firefighters now replaces part the Bitteroot Trail with this ugly scar on the landscape.

My hope is that the Forest Service will at least decommission the bulldozer tracks, as they not only obliterated a popular trail, but also destroyed a significant amount of savannah grassland that should be restored. Time is of the essence, too, as the cool-season grassland growing season has already begun in the East Gorge and typically ends by early June.

Many wildflowers will return to the Burdoin burn this spring, and the oaks and Ponderosa pine will return in time. But unless restored, this man-made scar will remain for decades – a scar on the land and for those who cherished this trail.

So, what will happen to the Bitterroot Trail? If the Forest Service does not restore the bulldozer road, then the same hikers who have unofficially maintained this trail for decades will now be tasked with “unofficially” undoing the harm done by the bulldozers as part of restoring the trail. A better solution would be for the agency to come around to the idea of doing both: remediate the damage to the meadow by decommissioning the road, while also being open to formally recognizing a trail that has long brought the public to this area – including re-routing, if needed to provide a sustainable tread.

The following is a visual tour of the bulldozer track that replaces what was once the upper half-mile of the Bitterroot Trail.

The new cat road was already channeling runoff and eroding precious soil from these meadows in mid-December, even before the heavy rains arrived later that month. Had it been decommissioned ahead of the winter rainy season this scar could have been recovering along with the surrounding meadows.

Cat tracks and deeply gouged ruts mark the new road, with no drainage features to manage runoff and erosion, though it runs directly downslope across the meadows.

In this view, the cat tracks on the right had already been erased by heavy rill erosion that was actively stripping soil from the scar.

Near the upper end of the new cat track, the main impact was to disturb the cobbled bedrock that is just inches below the thin meadow soil in this area, leaving rock piles and ruts that will persist for decades unless they are decommissioned and the area restored to its pre-fire condition.

On the day I visited in mid-December, hikers following the Bitterroot Trail were already attempting to navigate the bulldozer track, slipping on loose cobbles, through mud holes, or heading cross-country to avoid the mess, and thus further impacting the meadows. Like me, many were probably encountering the destruction for the first time on a day when they were already absorbing the impact of the fire on the ecosystem. It was hard to watch.

The Bitterroot Trail survived this steep stretch of cat road construction, where the bulldozers briefly ran parallel to the trail. While the environmental impacts and sustainability of user trails are valid Forest Service concerns, the brutality and carelessness of the new cat road renders the argument moot in this side-by-side comparison.

What should have been a relaxing, rejuvenating day on the trail for this couple turned into an ankle-twisting exercise in frustration as they discovered that part of the Bitterroot Trail had been destroyed, replaced by a crude cat road. Here, they are descending the steep, loose section shown in the previous photo.

While a section of the Bitterroot Trai has been destroyed, the views have not. This pair stopped to take in the sweeping panorama before continuing their scramble along the new cat road to the resumption of the Bitterroot Trail.

As I watched the pair shown above struggle through the frustrating mess, then suddenly pause at the astonishing view that unfolded before them, I regained my optimism that we can make this right. Catherine Creek – and the Gorge – are simply too precious to be treated this way. This is undeniably a world-class landscape, and even if our public land agencies don’t always live up to that standard, I do believe that our collective appreciation of the unique beauty and vulnerability of landscape will lead us to do better.

Next up: Catherine Creek East

The third and final piece in this series is more uplifting (I promise!) and will focus on the eastern savannah of Catherine Creek, where the fire was more clearly beneficial in sustaining the grassland ecosystem.

Thanks for taking the time to read this far, and for visiting the blog!

_____________

Tom Kloster | February 2026

(Postscript: have you visited the new companion WyEast Images Blog? Be sure to subscribe while you’re there!)