The blossoms of the Western Pasque Flower emerge just after snow melt

The earliest visitors to the Mount Hood high country are among the lucky few to see Western Pasque Flower (Anemone occidentalis) in bloom. The cream-colored blossoms of these plants emerge in meadows and on sandy mountain slopes as soon as the snow melts, often along the margins of lingering snow patches. Western Pasque bloom even before their foliage emerges, allowing the plants to accelerate seed production in the short mountain summers.

After just a few days in bloom, the petals drop, and the Western Pasque enters a second stage, where the flower heads take on the form of a green sea anemone, with balls of soft spikes rising above emerging, fern-like foliage.

The second phase of the Western Pasque Flower, when the new seedheads are in their sea anemone form

The second phase goes unnoticed by most mountain visitors, lost in the green of rapidly awakening meadows. But during this phase, the seedheads begin their metamorphosis to the final stage that gives Western Pasque Flower its best-known persona.

In this phase, the prickly “sea anemone” globes suddenly grow an impressive mane of white hair that is like no other alpine flower. The dramatic seedheads of the Western Pasque persist at this stage from late July well into the fall, when the seeds are finally distributed.

The final phase of the Western Pasque Flower, when it becomes the Old Man of the Mountains

The whimsical appearance of the Western Pasque in this final form has given rise to a number of equally colorful common names:

• Old Man of the Mountain

• Tow-Headed Baby

• Mop Top

• Hippie-on-a-Stick

• Mouse-on-a-Stick

As a child of the 70s, I suppose it’s not surprising that I call them “Muppets of the Mountains”. They’re like an old friend to hikers, greeting us as we venture to our favorite alpine meadows and swales on bright summer weekends, waving in the breeze with their silky “wigs” growing more curious and eccentric by the day.

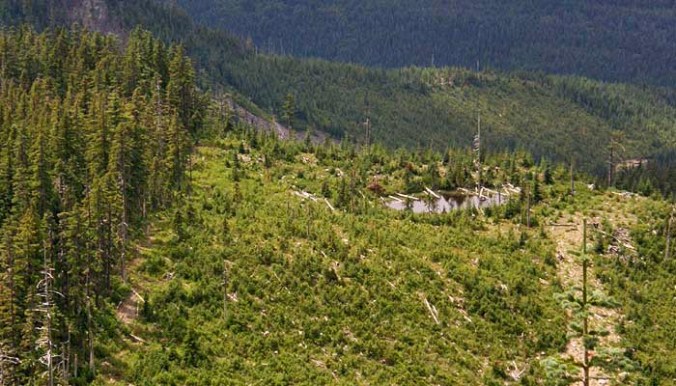

Western Pasque Flower carpet Elk Cove in summer

If Native Americans gathered these plants, their local use was apparently not passed along to anthropologists. Other American species of Anemone were used by Native Americans for a variety of medicinal uses, but perhaps the high-elevation range of the Western Pasque simply made it impractical to harvest? In most years, the high meadows that these plants call home are only snow-free for 3-4 months in summer.

Today, you can find Western Pasque Flower above 5,000 feet in Mount Hood’s alpine meadows and steep, sandy slopes. The plants are most prolific at Elk Cove and Paradise Park, but can be founds along many sections of the Timberline Trail, blooming in mid-July and in their more familiar bearded form from Late July through September.