Mount Hood’s scenic wonders beckon on the final approach to the Vista Ridge trailhead on Forest Road 1650

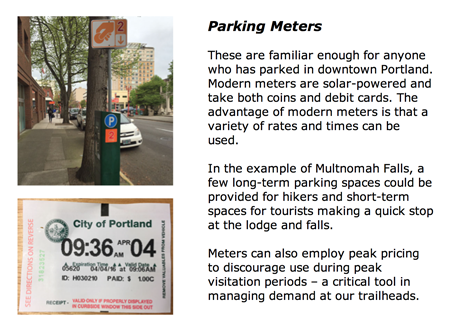

Public lands across the nation experienced a big spike in visitors during the recent pandemic, continuing a growth trend that has been in motion for decades. In WyEast Country, this has placed an unprecedented burden on some of Mount Hood’s under-developed trailheads, like the one at Vista Ridge, on the mountain’s north side.

The scenic gems within a few miles of this trailhead are among the mountain’s most iconic: Cairn Basin, Eden Park, Elk Cove, WyEast Basin and Owl Point draw hikers here, despite the washboards along the dusty final gravel road stretch – and the completely inadequate trailhead.

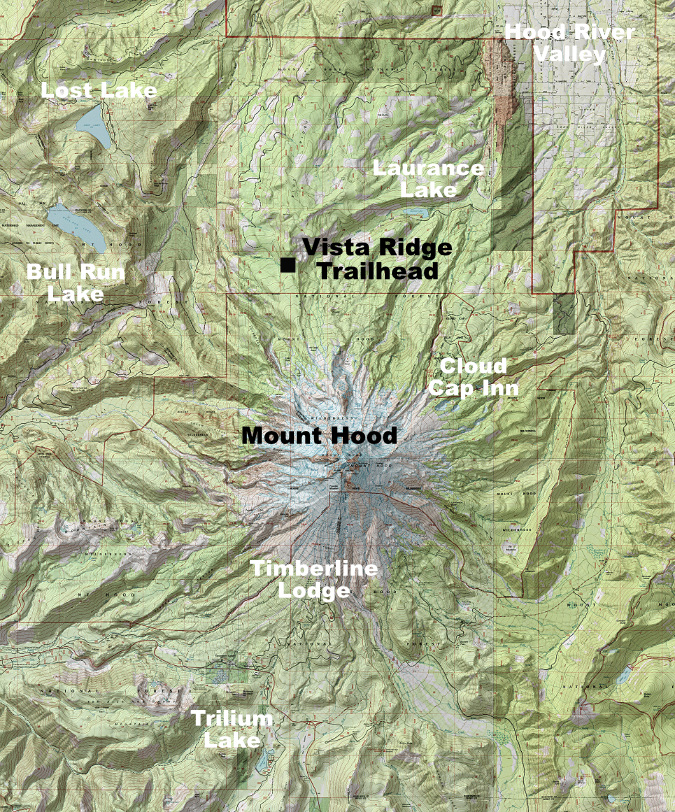

The Vista Ridge is located on Mount Hood’s rugged north side and reached from Lolo Pass Road

The pandemic isn’t the only driver in the growing popularity of Vista Ridge. The 2011 Dollar Lake Fire torched Vista Ridge, leaving a vast ghost forest behind. In the years since, the forest recovery has featured a carpet of Avalanche Lilies in early summer that draws still more visitors to this trailhead. And since 2007, volunteers have restored the Old Vista Ridge trail to Owl Point, adding yet another popular hiking destination here.

It is abundantly apparent to anyone using the existing Vista Ridge trailhead that it was never designed or developed to be one. Instead, it was the result of a plan during the logging heyday of the 1960s to extend Forest Road 1650 over the crest of Vista Ridge and connect to the growing maze of logging roads to the east, in the Clear Branch valley.

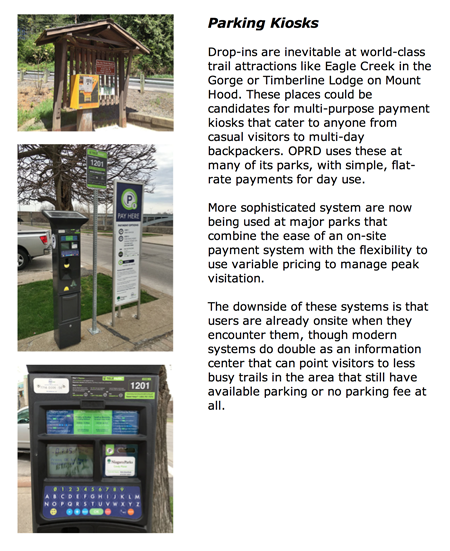

For reasons unknown, that never happened, and by the late 1960s the road stub defaulted into an unimproved trailhead for the Vista Ridge Trail when a short trail connection from the road stub to the saddle was built, instead. This new trail connection short-circuited the northern two miles of the Vista Ridge trail, but has since been restored reopened as the Old Vista Ridge trail. This is how today’s Vista Ridge trailhead came to be on a steep hillside at the abrupt end of a defunct logging spur.

The existing Vista Ridge trailhead is simply a logging spur that was abandoned mid-construction in the 1960s, and thus lacks even a simple turnaround

While it was still lightly used as recently as the early 2000s, the popularity of the Vista Ridge trailhead has grown dramatically over the past 15 years. Today, dozens of cars are shoehorned into this dead-end spur during the busy summer hiking season.

Parking at the trailhead is a haphazard affair, at best. There is room for about 6 cars along the south edge of the stub, though it was never graded for this purpose, and thus even these “spaces” are a minefield of sneaky, axel-cracking pits and oil-pan ripping boulders. These semi-organized spaces fill immediately on summer days, so most who come here end up parking at the stubbed-out end of the spur or spill out along the narrow final approach of Road 1650.

Overflow from the cramped existing trailhead routinely spills over to the narrow Road 1650 approach during the summer hiking season

Spillover parking on this section of Road 1650 is only unsafe for passing vehicles, it also impacts a resident Pika population living in these talus slopes

Because the existing trailhead was never designed or graded as a parking area, visitors must navigate large boulders and deep pits to find parking

The scars on this boulder are testimony to the real damage caused by the lack of an improved parking surface at the existing Vista Ridge trailhead

The constrained, chaotic parking at the Vista Ridge Trailhead and resulting overflow on busy weekends is frustrating enough for visitors, but it also creates a safety problem for emergency response. This trailhead provides the best access to the northern part of the Mount Hood Wilderness, yet there is often no way to turn a vehicle around in summer, much less park a fire truck or ambulance here.

The overflow parking on the narrow access road is not only stressful an potentially dangerous for visitors to navigate, it also creates an access problem for larger emergency vehicles attempting to reach the trailhead

This visitor was forced to back nearly 1/4 mile down the access road after reaching the full parking lot and overflow shoulder parking that left no room to turn around

The origins of the short trail connector from today’s trailhead to the historic Vista Ridge Trail has unclear origins, it appears to have been built between 1963 and 1967, and it was clearly intended to replace the northern portion of the Vista Ridge Trail – the section that has since been restored as the Old Vista Ridge Trail.

While most of the short connector trail is a well-constructed and graded route through dense forest, the first 200 yards are a miserable, rocky mess where the “trail” is really just a rough track that was bulldozed for a planned extension of the logging spur, but never fully graded. This sad introduction to the wonders that lie ahead is a frustrating chore to hike – and an ankle-twisting nightmare to re-negotiate at the end of your hike.

This signpost is the sole “improvement” at the Vista Ridge trailhead, leaving much room for improvement at what has become one of Mount Hood’s most popular trailheads

The first 1/3 mile of the Vista Ridge trail follows an abandoned, partially constructed section of logging spur that has significant surface and drainage problems that also leave much room for improvement as the gateway to this popular area

Add to these trailhead and trail condition woes an ongoing lack of proper signage to help people actually find Vista Ridge, and you have a discouraging start to what should be stellar wilderness experience for visitors – many from around the country and even the world. Thus, the following: a proposal to finally fix these issues at Vista Ridge and give this sub-par portal into the Mount Hood Wilderness the attention it has long deserved.

The Proposal…

The problems that plague the existing Vista Ridge Trailhead all stem from its accidental location on the steep mountainside. As a result, there is no way to safely accommodate needed parking, a turnaround or other trailhead amenities in the current location. The good news is that flat ground lies about 1/2 mile away, where Road 1650 passes an already disturbed site that was part of a recent logging operation.

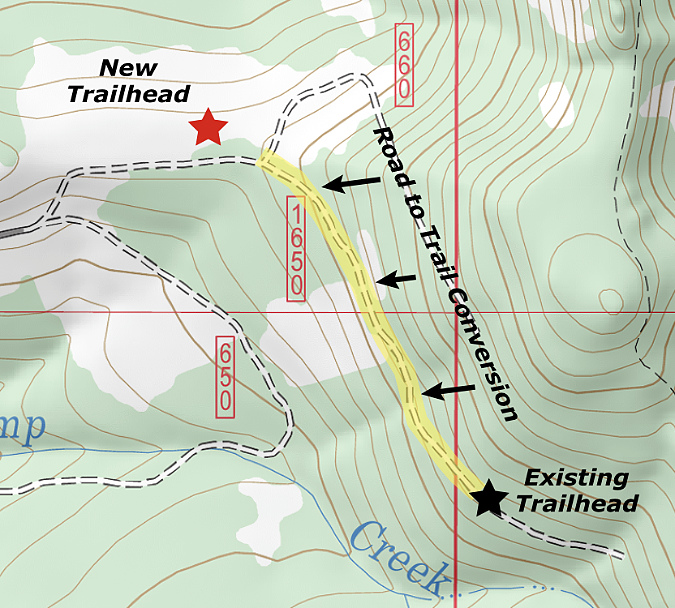

This map shows the proposed new trailhead site – roughly 1/2 mile northwest of the existing trailhead – and the section of existing road (highlighted in yellow) that would be converted to trail

To make this new location work, the section of Road 1650 from the proposed new trailhead to the old (highlighted above in yellow) would be converted to trail. Normally, adding a half-mile of converted road to a hike would be a minus, but this segment of Road 1650 is stunning (see below), with spectacular views of Mount Hood. The talus slopes that provide these views are also home to colonies of Pika that provide their distinctive “meep!” as you pass through – something that can’t be appreciated from a car.

Converted roads don’t always make for great trails, but the approach to the existing Vista Ridge trailhead is exceptionally scenic and would make for a fine gateway trail to the Mount Hood Wilderness

The first step in creating the new trailhead (and even without the new trailhead) would be restored signage to help visitors find their way from Lolo Pass Road to Vista Ridge, especially at the confusing fork (below) located just short of the proposed trailhead.

Finding the Vista Ridge trailhead is a challenge. The signpost at this crucial fork just below the trailhead had lost its sign in this view from two years ago, but the entire post has since disappeared. A new trailhead would include restoring directional signage to help visitors navigate the route

Next up, the obvious spot for the new trailhead (below) is a yarding area from a logging operation that was impacted more recently with a nearby thinning project. Dirt logging spurs radiate in all directions from this cleared area, allowing for new trailhead parking to incorporate these already impacted areas to minimize environmental impacts.

The proposed new trailhead site was previously disturbed with a logging operations

Until recently, the proposed new parking area faced a wall of trees to the south, but a tree thinning project on the opposite side of Road 1650 has suddenly provided a Mount Hood view (below). The purpose of the thinning was to enhance forest health by removing smaller, crowded plantation trees to promote huckleberries in the understory – an important first food harvested by area tribes.

Should the huckleberries thrive as planned and bring berry harvesters to the area, this could be another benefit of providing trailhead parking here. For now, the thinning just provide a sneak-peak at the mountain that lie ahead for hikers or a backdrop for people using picnic tables at the trailhead (more about that in a moment).

The proposed new trailhead is directly across Road 1650 from a recently thinned area

It looks pretty grim now, but the tree thinning project across from the proposed is intended to spur the huckleberry understory to allow for berry harvesting… eventually

The concept for the new trailhead parking is to use an old dirt logging spur that splits off the Vista Ridge Road as the entrance to the parking loop. The existing Road 1650 would be closed and converted to trail from this point forward. The logging spur is shown on the left in the photo below, along with the portion of Road 1650 where the trail conversion would begin. The existing trailhead lies about 1/2 mile from this point.

The existing road conversion to trail would begin here, with the new parking access following the logging spur on the left

Roughly 200 yards beyond the proposed trailhead, the views open up along existing Road 1650 where it crosses the first of two talus slopes (below). This is one of those “wow!” spots that comes as a surprise to hikers as they drive to the existing trailhead. The right half (downhill) in this converted section of the existing road would be retained as trail, the left (uphill) side would be decommissioned.

The final 1/2 mile of Road 1950 is scenic in all seasons, with Beargrass blooms in early summer and brilliant fall colors emerging by late summer

How does this work? The decommissioning of the uphill half of the existing road could be accomplished by upturning the surface with a backhoe – a process used to decommission miles of logging roads in recent years around Mount Hood country. The scene below is a typical example from a decommissioned road near Black Lake, located a few miles north of Mount Hood, on Waucoma Ridge. In this example, the goal was to completely retire the road, though the same method can be used to convert a road to single-track trail.

This road near Black Lake was decommissioned in the early 2000s and is gradually revegetating

Just beyond the first “wow!” talus viewpoint, the mountain comes into view once again along the existing Road 1650 as it crosses the second talus slope, just before reaching the existing trailhead. This slope here is unique in that it consists of red lava (below), a somewhat uncommon sight around Mount Hood that adds to the scenic beauty. Like the first talus section, this slope is also home to Pika colonies, adding to the trail experience. The right half of the converted road would be retained as trail here, and the left (uphill) side decommissioned.

Without overflow parking blocking the view, the final stretch of the access road passes this scenic and somewhat unusual talus slope composed of red lava rocks

Beyond the practical benefits of moving the Vista Ridge trailhead to make it safer and more functional, there are also compelling conservation arguments for the move. First, it would allow the Forest Service to retire another segment of old logging road – and though only 1/2 mile in length, in its current state it nonetheless contributes to the massive backlog of failing roads built during the logging heyday that the agency can no longer afford to maintain.

There are also noisy (meep!) wildlife benefits, as the Pika colonies living in both talus slopes are likely impacted by the noise, vibration and pollution that the steady stream of hikers bring as they drive – and increasingly park – along this scenic section of road.

Because most road-to-trail conversions around Mount Hood have been driven by wilderness boundary expansions, washouts or other abrupt events, there aren’t many examples of intentional conversions to point to. Instead, most conversions are simply abandoned roadbeds that nature is gradually reclaiming, like the section of the Elk Cove trail shown below.

The lower section of the Elk Cove Trail follows an old logging road that was simply closed, but not formally converted to trail

Beyond often being a hot, dusty trudge for hikers looking for a true trail experience, old roads that aren’t intentionally converted also lack proper trail design features for stormwater runoff and drainage, as seen on the opening section of the existing Vista Ridge trail. Abandoned roads also lead to thickets of brush and young trees as the forest moves in, making maintenance of trails that follow these routes a constant chore. It simply makes more sense to undertake true conversions from road to trail on these routes in the long run.

Recently converted road-to-trail at Salmon Butte (Oregon Hikers)

There are very good examples of intentional conversions, and among the best is the Salmon Butte Trail, where the Forest Service decommissioned a section of road in 2010 and intestinally created meandering trail through mounds of earth along the old roadbed to further conceal evidence of the road from hikers. Just a few years after the conversion (above) the signs of the old road were already fading fast, creating a more authentic trail experience. Self-sustaining drainage features were also incorporated into the design. The same approach could be applied to decommission both the final road section and the current trailhead parking area at Vista Ridge.

Finally, improvements to the opening stretch of the existing Vista Ridge trail that also follows old roadbed is in order. This short section (below) is typical of a road that wasn’t property converted to trail, and as a result suffers from serious runoff erosion during the winter and spring. The result is a cobbled mess that is hard on ankles and morale as hikers set off for their hike.

If this looks like a dry streambed, that’s because it is! It’s also the opening 1/3 mile section of the Vista Ridge Trail where it follows an abandoned, partly constructed road bed that becomes a running stream in the winter months

There are some basic trail drainage features that could keep this section from becoming a river during the wet months. Next, some of the most miserably rocky sections could be covered with gravel – but from where? It turns out the Forest Service left a couple of large piles (below) where today’s trailhead is located when work on extending this road was abandoned more than 50 years ago.

A Northwest Youth Corps crew did just this about a decade ago, but because the drainage problem wasn’t addressed, most of that first layer of gravel has been washed away and their efforts long since erased.There are some basic trail drainage features that could keep this section from becoming a river during the wet months. Next, some of the most miserably rocky sections could be covered with gravel – but from where? It turns out the Forest Service left a couple of large piles (below) where today’s trailhead is located when work on extending this road was abandoned more than 50 years ago.

Let’s put this leftover pile of gravel from the logging days to work!

How a parking loop would work…

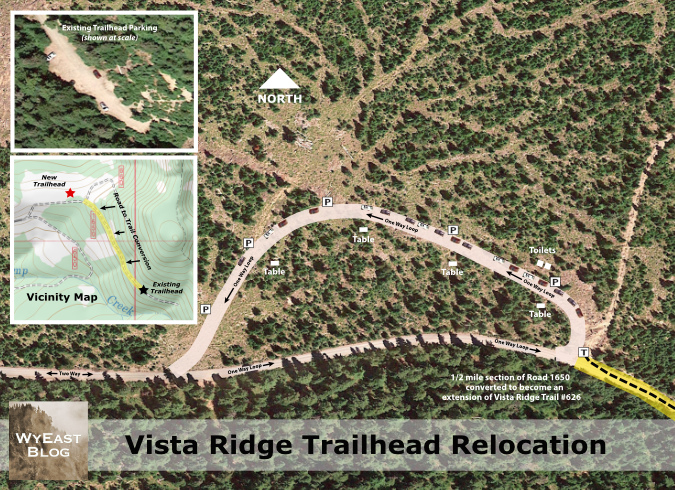

Putting it all together, this proposal (below) shows how the new trailhead parking could be accomplished as a parking loop, as opposed to a parking lot. The inset images include an aerial image of the current, dead-end trailhead parking at the same scale as the proposed loop map for direct comparison. The topographic inset map shows the proposed trailhead and parking loop, along with the proposed road conversion in relation to the existing trailhead (be sure to click on “large version” link below for a closer look!)

[click here for a large version]

Why a loop? First, it’s the least impactful on the environment. Instead of clearing a wide area to provide room for cars to back in and out, the parking is simply provided along the right shoulder of the loop – like parallel parking in the city – but with nature left intact inside the “donut hole” of the loop.

In this case, the loop would follow a series of old logging skid roads, further minimizing the impact on the forest. But perhaps most importantly from an environmental impact perspective, adding a couple hundred yards of new loop road here would allow a half-mile section of existing road to be retired and converted to trail, a clear net gain, overall.

Busy trailheads call for amenities like improved signage and toilets – and space for emergency vehicles to have access. These vehicles were called to the trailhead where a hiker was injured in the Clackamas River area – fortunately, the trailhead was located along a paved forest road with ready access and space to turn around

Another important benefit of a loop is to provide a much-needed turnaround at the end of a dead-end road for forest rangers and emergency responders. This might be the most compelling reason to fix the Vista Ridge trailhead sooner than later, as today’s overflowing dead-end parking area is a disaster waiting to happen should fire trucks or other emergency vehicles need to access the Vista Ridge trail on a busy weekend.

Designing the parking loop…

From a user perspective, a parking loop is efficient and easy to navigate. The one-way design ensures that people arriving here would always reach the closest available parking spot to the trailhead first. This is the opposite of the current dead-end trailhead, where hikers arriving later in the day often park in less-than-safe spots along the access road when they see overflow shoulder parking occurring, for fear of not being able to turn around in the cramped trailhead lot – often after spaces have opened up in the main parking area.

As shown in the parking schematic (above), the relocated trailhead would accommodate up to 30 vehicles along a 1,100-foot-long loop – or about three times what the current dead-end parking area allows. The loop would be gravel-surfaced, 16-feet wide and designed to flow one-way in a counter-clock-wise direction, with shoulder parking allowed on the right side.

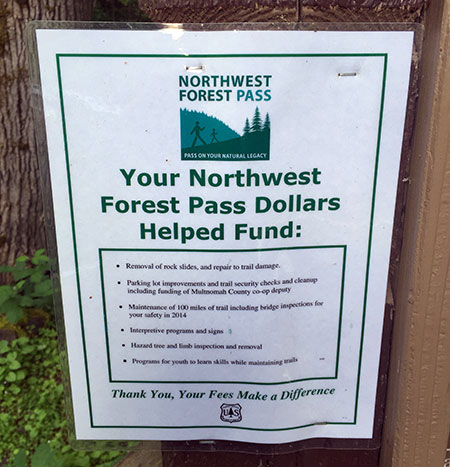

The new trailhead could also be a Northwest Forest Pass site with the required toilets, picnic tables and welcoming signage for visitors, something that the space constraints at the current lot would not allow. These could be located in the “donut hole” center of the loop. Making this a forest pass site would also address one of the more dire needs at Vista Ridge – a toilet! The heavy use at the trailhead and steep terrain has turned a couple of more accessible trees adjacent to the parking area into de-facto toilets, with unpleasant results.

Industrial toilets at a busy trailhead in the Columbia Gorge – functional, but not exactly a complement to the outdoor experience!

The Forest Service has upped its game with pit toilets in recent year at some Northwest Forest Pass sites, replacing industrial porta-potties (above) that are the last thing you want to see as you set off for a wilderness experience with more aesthetic toilets, like the one at the High Prairie trailhead (below), just east of Mount Hood. This would be a great choice for a new trailhead at Vista Ridge.

Rustic toilet design at the High Prairie trailhead, gateway to the Badger Creek Wilderness

The are also more substantial examples around Mount Hood that are wheelchair accessible, like this one at the Billy Bob snow park near Lookout Mountain (below).

Accessible, rustic toilet design at the Billy Bob snow park near Lookout Mountain

Why an accessible toilet? Because there’s also an opportunity for the converted road section in this proposal to incorporate an accessible trail surface to at least one of the talus viewpoints along the way – like this well-photographed spot along the existing road (below), located just a few hundred yards from the proposed trailhead.

This view is from the shoulder of the current access road, just a few hundred yards from the proposed new Vista Ridge trailhead. Converting the road to an accessible trail design and providing some simple amenities (e.g., a picnic table) would make this a welcome new destination for people with limited mobility or who use mobility devices

Accessible trail opportunities are in woefully short supply around Mount Hood, an unacceptable reality. There’s room at this viewpoint for an accessible picnic table, benches and perhaps interpretive signage — allowing for the extended Vista Ridge trail to serve a wider spectrum of visitors and abilities, not just able-bodied hikers heading into the wilderness.

What would it take?

There are two main parts to this proposal: (1) building the new parking loop and (2) converting the final half-mile section of Road 1650 to become a trail. The first part – the parking loop, pit toilets, picnic tables, signage and other trailhead amenities — would have to be built by the Forest Service. However, this work could likely be fast-tracked as an exemption under the environmental review process, since it involves relocating an existing parking area and would result in much less roadway than the current trailhead. That environmental analysis would also have to be completed by the Forest Service.

The second part of this proposal — the road-to-trail conversion — could be completed as a partnership between the Forest Service and volunteers, like Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO), who already maintain the Old Vista Ridge and Vista Ridge trails. The Forest Service could complete the rough backhoe work to reduce the converted road to single track, and volunteer crews could finalize the tread and drainage on the converted trail.

Volunteers could also install viewpoint benches and picnic tables for an accessible trail and trailhead signage at the new parking area. Some of the heavier work could be contracted to organizations like the Northwest Youth Corps, which has a long history of trail work around Mount Hood.

Northwest Youth Corp crew working on the Vista Ridge Trail

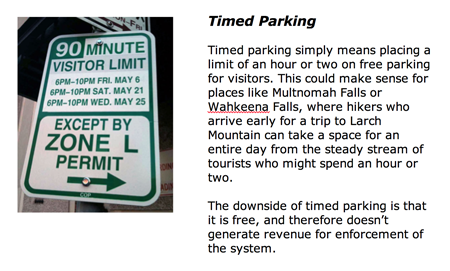

How could this concept move forward? Funding is always a concern for the Forest Service, but there’s also unprecedented funding coming online right now for the federal agencies from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. This project could compete for these funds, many of which are competitive, especially if it includes an accessible trail. Creating a new Northwest Forest Pass site would also generate revenue (in theory) to help maintain the new trailhead.

Volunteer crews from TKO are already working from this trailhead every summer to maintain the Vista Ridge and Old Vista Ridge trails. The over-crowding at the existing trailhead has already made their work more difficult, so contributing to the trail conversion effort would be a natural fit for TKO volunteers to be part of.

The author on the Old Vista Ridge trail

In the meantime, if you want to experience the wonders of Vista Ridge and Old Vista Ridge, the best plan is to avoid this trailhead on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from July through mid-September. If you must go on those days, then it’s not a bad idea to simply park on the shoulder of Road 1650 where this new trailhead is proposed, and simply walk the scenic final half mile to the current trailhead. You’ll get mountain views, hear the local pikas calling out, avoid the stressful chaos of the existing trailhead – and with any luck, you’ll be getting a preview of things to come!

__________________

Tom Kloster | August 2023