The current controversy over the proposed Palomar utility corridor (that would slice across the Clackamas River country, south of Mount Hood) is an uncanny reminder of the 1950s disaster that brought the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) transmission lines to Lolo Pass, north of Mount Hood. In both cases, the result is a permanent, linear clearcut running up and down mountainsides, with almost no regard for visual or environmental impact.

The disastrous BPA transmission corridor over Lolo Pass set a new low for siting transmission corridors

The BPA lines came with the completion of the John Day and The Dalles dams, along the lower Columbia River. As if drowning the incomparable Celilo Falls weren’t enough, the transmission lines crested the Cascades at Lolo Pass, at the time one of the more remote and spectacular corners of the Mount Hood backcountry.

In the 1950s, American society was still in the early years of sprawling hydroelectric projects and rows of transmission towers marching toward the horizon. At the time, these images equaled progress, and nothing more.

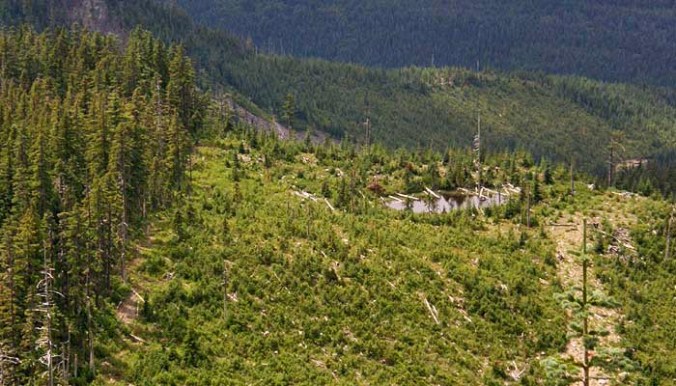

Transmission corridors are straight, but nature is not: the BPA corridor saws across the shoulder of Sugarloaf Mountain in this view

But the BPA lines over Lolo Pass marked a particularly senseless disregard for the landscape, needlessly ruining mountain valleys, blocking Mount Hood vistas, and creating a permanent nuisance with the permanent clearcut that is maintained along the corridor.

The transmission lines also brought a new road to Lolo Pass, along with a devastating logging program that nearly cleared the Clear Fork and Elk Creek valleys, along the corridor. The permanent clear cut below the transmission lines was maintained for decades with chemical herbicides, though the BPA has more recently bowed to pressure to maintain their swath of destruction with mechanical methods.

Over the years, the lines have multiplied, and today, the Lolo Pass swath encompasses four large transmission lines in a quarter-mile wide swath. The maze of “closed” dirt maintenance roads below the lines are a perennial draw for target shooters, off-highway vehicles and illegal dumpers. These activities, in turn, have helped turn the linear clear cut into a conduit of invasive species, brining Scotch broom and Himalayan blackberry deep into the Cascades.

The Lolo transmission corridor began on the scale of the Palomar proposal, but has grown over time

The lessons from the Lolo Pass disaster are many, but above all, we’ve learned that a single utility corridor will almost surely grow over time, as utility planners make the case that future lines ought to follow these existing paths of least resistance.

We’ve also learned that the visual and environmental blight that the corridors create is insidious, causing forest managers to discount the value of adjacent, intact forests as somehow tainted — as less worthy of protection or even recreation use. This will surely be the case if the Palomar corridor is approved.

But the story of Lolo Pass is not complete, and the final chapter has yet to be written. Why? Because after just 50 years, the BPA lines are already approaching their design life, and will eventually need to be replaced.

Mount Hood towering above Lolo Pass

Under the logic that led to the expansion of this corridor to encompass four parallel transmission lines, it would be easy to assume that the towers and lines will simply be replaced in place, within the existing corridor.

But it will be equally possible to imagine something better for Lolo Pass — relocating the corridor and restoring the pass, and perhaps finding a better, more efficient, less destructive way to transport our energy.

That’s the dream and vision for many who hold the former beauty of Lolo Pass in their memories, and can imaging restoring this corner of the mountain to its fomer splendor. But it’s also a reminder not to repeat the Lolo Pass mistake at Palomar, setting yet another legacy of perpetual, linear destruction in motion.