(Click here for a larger view)

It was the summer of 1939, and Depression-era Americans were escaping the hard times with the theater releases of “Gone with the Wind” and “The Wizard of Oz”. In Europe, Hitler’s invasion of Poland in September of 1939 ignited World War II.

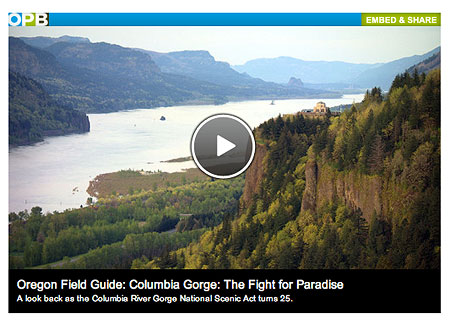

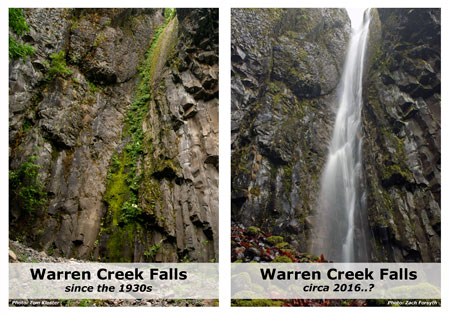

Against the sweeping backdrop of this pivotal year in history, a odd story was playing out on obscure Warren Creek, near Hood River in the Columbia River Gorge. This is the story of how today’s manmade Hole-in-the-Wall Falls was created, and Warren Falls was (temporarily, at least) lost to time. It all began 15,000 years ago…

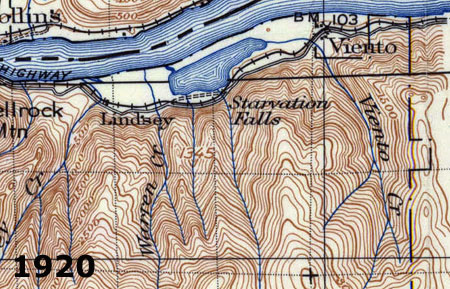

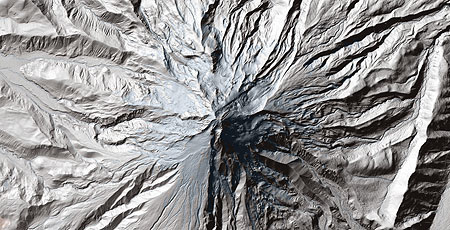

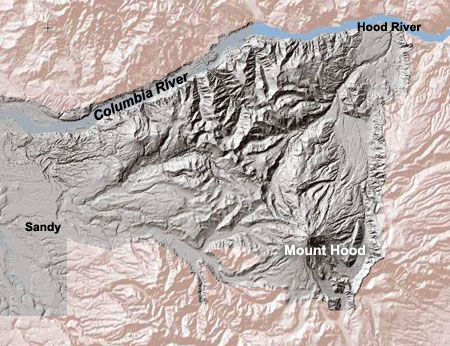

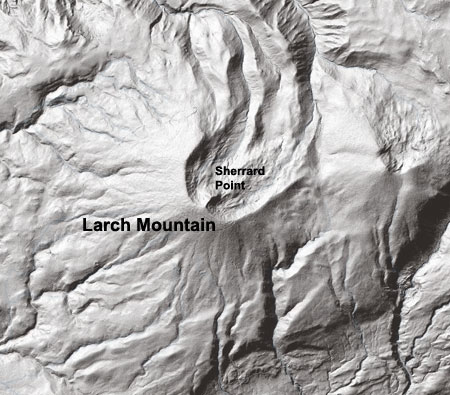

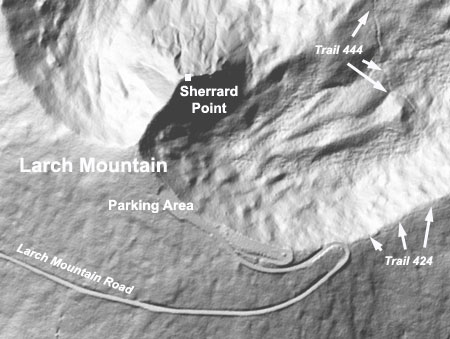

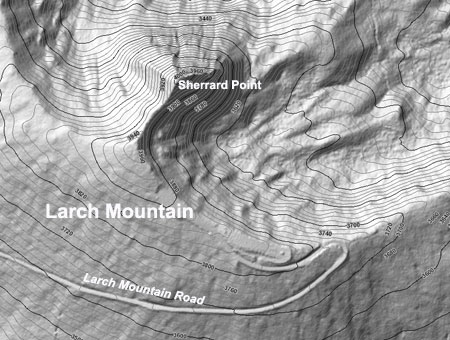

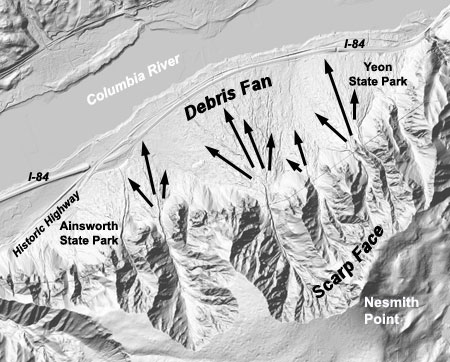

15,000 Years Ago – The string of waterfalls on Warren Creek were formed as a result of the Bretz Floods. Also known as the Missoula Floods, these were a cataclysmic series of bursts from glacial Lake Missoula that scoured out the Columbia River Gorge over a 2,000 year span. The events finally ended with the ice age, about 13,000 years ago.

Today’s rugged cliffs in the Columbia Gorge were over-steepened by the Bretz floods, leaving tributary streams like Warren Creek cascading down the layers of sheer, exposed basalt bedrock. Geologist J. Harlen Bretz published his theory describing the great floods in 1923, just a few years before Warren Falls would be diverted from its natural channel.

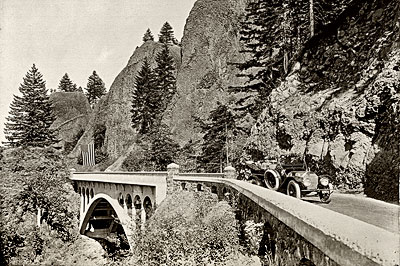

June 6, 1916 – Samuel Lancaster’s Columbia River Highway is dedicated, and immediately hailed as one of the pre-eminent roadway engineering feats in the world. The spectacular new road brings a stream of touring cars into the Gorge for the first time, with Portlanders marveling at the new road and stunning scenery.

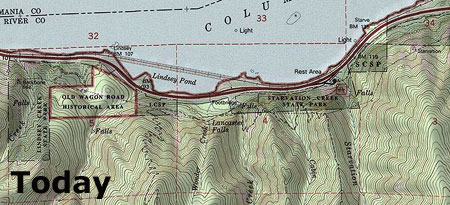

Lancaster’s new highway passed Warren Falls under what is now I-84, crossing Warren Creek on a small bridge, and passing two homesteads, a small restaurant and service station that were once located near the falls. Today, this section of the old road is about to be restored as a multi-use path as part of the Historic Columbia River Highway project.

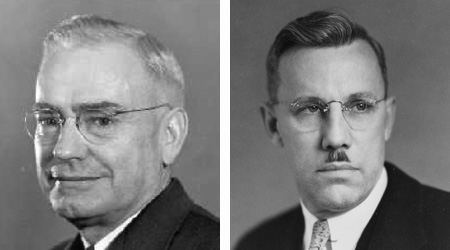

July 29, 1939 – Robert H. “Sam” Baldock is midway through his 24-year tenure as Oregon State Highway Engineer (1932-1956), an influential career spanning the formative era of the nation’s interstate highway era. Baldock advocated for the construction of what would eventually become I-84 in the Columbia Gorge, initially built as a “straightened” US 30 that bypassed or obliterated Samuel Lancaster’s visionary Columbia River.

Thirties-era Chiefs: Oregon Highway Engineer Sam Baldock (left) and Assistant Highway Engineer Conde B. McCullough (right)

In a letter to the Union Pacific Railroad, Baldock describes an ingenious “trash rack” and bypass tunnel at Warren Falls that had just been released to bid, on July 27. The project was designed to address an ongoing maintenance problem where Warren Creek had repeatedly clogged the openings on the old highway and railroad bridges with rock and log debris.

While the Baldock proposal for Warren Creek seems a brutal affront to nature by today’s standards, an irony in this bit of history is that his assistant highway engineer was none other than Conde B. McCullogh, the legendary bridge designer whose iconic bridges define the Oregon Coast Highway.

McCullough designed several bridges along the Columbia River Highway, as well, yet he apparently passed on the opportunity to apply a more elegant design solution to the Warren Creek flooding problem. Otherwise, we might have an intact Warren Falls today, perhaps graced by another historic bridge or viaduct in the McCullough tradition!

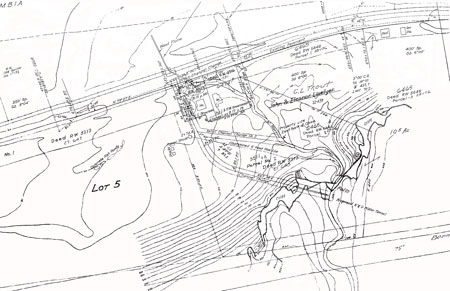

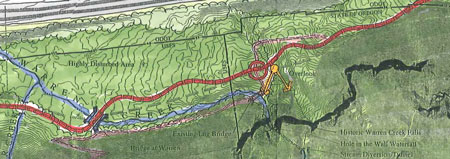

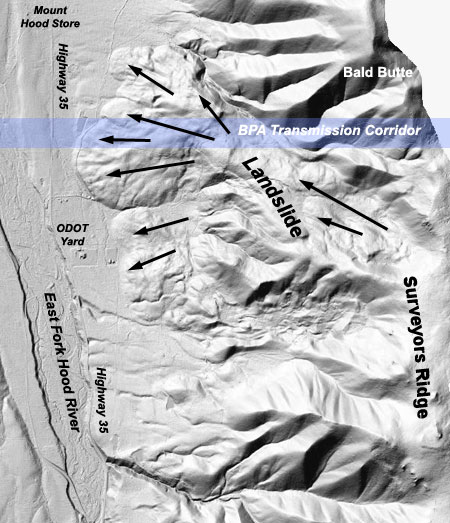

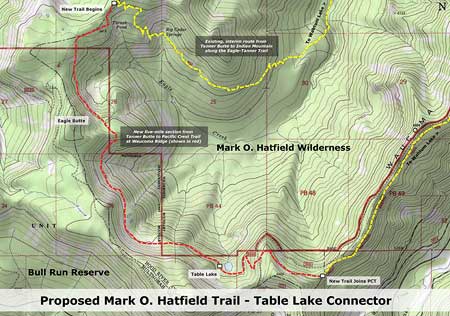

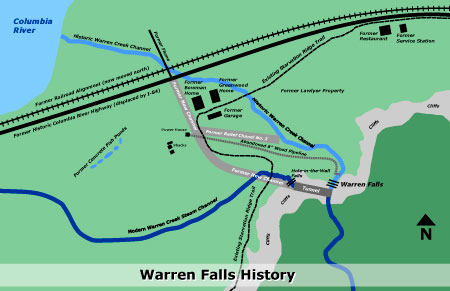

(Click here for a larger view of this map)

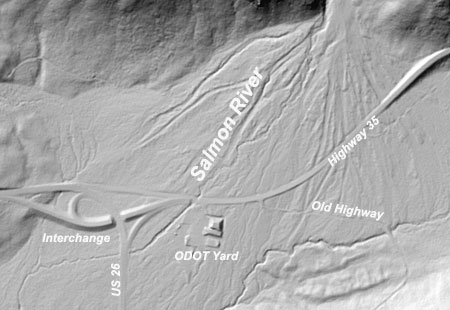

At the time of the Warren Falls diversion project, the railroad was located adjacent to the highway (it was later moved onto fill in the Columbia River when the modern I-84 alignment was built in the 1950s).

The Union Pacific had already attempted to address the Warren Creek issue with a flume built to carry the stream over the railroad and away from the railroad bridge. This initial effort by the railroad appears to have been the catalyst for a joint project with ODOT to build an even larger diversion.

This map blends historic information from ODOT site plans with the modern-day location of Warren Creek.

(Click here for a larger view of this map)

August 10, 1939 – Union Pacific Railroad Resident Engineer S. Murray responds to Baldock’s July 29 letter, praising the “trash rack” and tunnel design solution, but also offering an alternative approach to the tunnel scheme:

“I think possibly we have all approached this problem from the reverse end. Above the falls there is a deposit of gravel about 600 feet long and of varying widths and depths, and possibly there are 10,000 yards of it ready to move.

Would it not be practicable and sensible to simply hoist a cat up the cliff and into the canyon and push this material down over the falls and then away from the course of the water, and then construct a small barrier of creosoted timber so as to hold back future deposits until they accumulate in sufficient amount to justify their being moved again?”

In the letter, Murray suggests that Baldock’s Highway Department do a comparative cost analysis of this alternative, as he expected to “have difficulty in obtaining approval” of the Union Pacific’s participation in the project “under [the] present railroad financial situation.”

The Union Pacific proposed hoisting a bulldozer like this one to the top of Warren Falls and using it to push debris over the brink!

August 30, 1939 – In his response to Murray, Sam Baldock declines to consider the counter proposal to simply bulldoze the debris above Warren Falls as an alternative to the tunnel project, and instead, continues advancing a $14,896.27 construction contract to complete the diversion project for Warren Creek.

September 2, 1939 – Murray responds immediately to Baldock’s August 30 letter. With disappointment and surprising candor, he dryly quotes a 1934 letter where Baldock had proposed completely moving both the highway and railroad to the north, and away from Warren Falls, as a solution to the debris problem, apparently to underscore his belief that Baldock’s tunnel project would be a short-term, costly fix at best.

This earlier 1934 correspondence from Baldock turns out to be prophetic, of course, with the modern-day alignment of I-84 and the Union Pacific railroad ultimately carrying out Baldock’s vision.

Baldock’s faster, straighter version of the Columbia River Highway began to emerge in the 1940s (near Mitchell Point).

These proposals for altering Warren Creek may seem brazen and completely irresponsible by today’s environmental standards, but consider that at the time the dam building era on the Columbia River was just getting underway. By comparison, these “improvements” to nature were just another effort to conquer the land in the name of progress.

These schemes also underscore how visionary Samuel Lancaster really was: far ahead of his colleagues of the day, and some 75 years ahead of the 1990s reawakening among engineers to “context sensitive” design in the modern engineering profession.

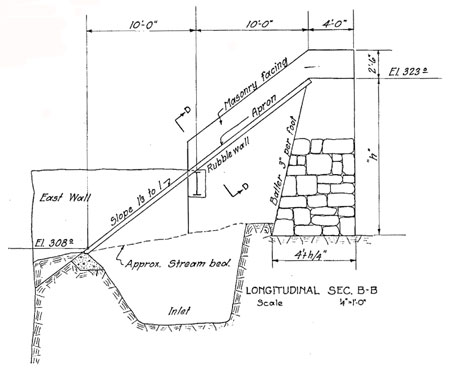

Cross-section plans for the “trash rack” design at the head of the Warren Creek diversion tunnel; the odd structure still survives and continues to function today.

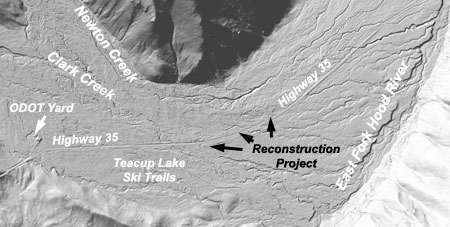

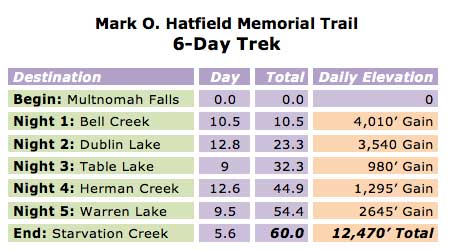

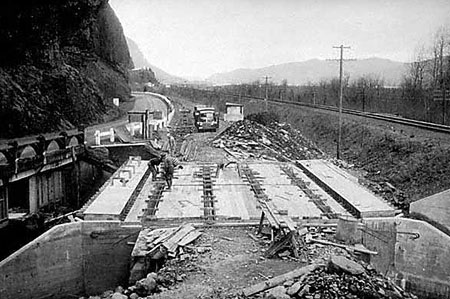

October 2, 1939 – Work on the Warren Falls diversion project begins. The full project includes the diversion tunnel and flume, plus reconstruction of a 0.69 mile section of Lancaster’s historic highway and two bridges. In the fall of 1939, the highway contractor built a highway detour road, new highway bridges, and excavated the flume ditch and relief channels.

Work on the “trash rack” and associated blasting for the diversion tunnel bogged down, however, with the contractor continuing this work through the winter of 1940. Despite the modest budget, ODOT records show that the contractor “made a very good profit” on the project, and completed work on September 21, 1940.

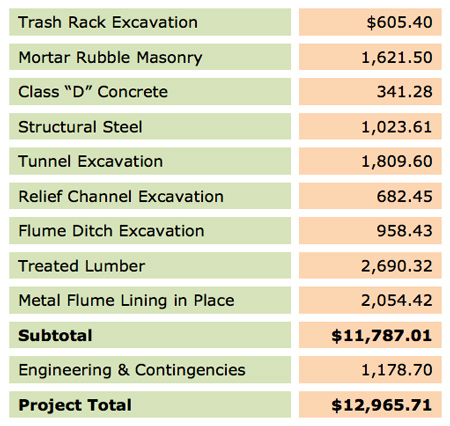

The budget for the project was as follows:

Compared to modern-day transportation projects that routinely run in the millions, seeing costs detailed to the penny seems almost comical. Yet, at the time both the Oregon Highway Department and Union Pacific Railroad were strapped for cash, and very cost-conscious about the project. A series of letters between the sponsors continued well beyond its completion to hash out an eventual 50/50 agreement to pay for construction and ongoing maintenance of the stream diversion structures.

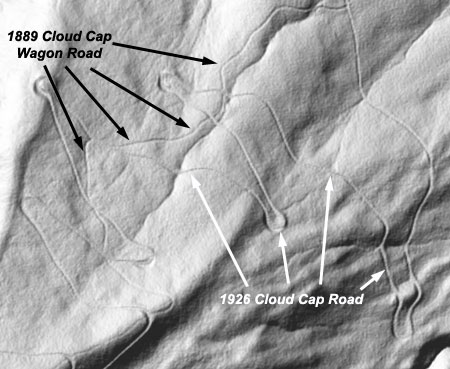

After the 1940s – the reconstruction of the Columbia River Highway at Warren Creek was part of a gradual effort to widen and straighten US 30 along the Columbia River. Today’s eastbound I-84 still passes through the Tooth Rock Tunnel, for example, originally built to accommodate all lanes on the straighter, faster 1940s version of US 30.

The beginning of the end: construction of the “new” bridge at Oneonta Creek in 1948, one of many projects to make the old highway straighter and faster. Both this bridge, and the original Lancaster bridge to the right, still survive today.

By the early 1950s, most of Sam Lancaster’s original highway had been bypassed or obliterated by the modernized, widened US 30. Much of the new route was built on fill pushed into the Columbia River, in order to avoid the steep slopes that Lancaster’s design was built on.

Passage of the federal Interstate and Defense Highways Act in 1956 moved highway building in the Gorge up another notch, with construction of I-80N (today’s I-84) underway. The new, four-lane freeway followed much of the US 30 alignment, though still more of Lancaster’s original highway was obliterated during the freeway construction. This was the final phase of freeway expansion in the Gorge, and was completed by 1963.

In the Warren Creek area, interstate highway construction in the late 1950s finally achieved what Sam Baldock had envisioned back in his correspondence of 1932, with the Union Pacific railroad moved onto fill reaching far into the Columbia River, creating what is now known as Lindsay Pond, an inlet from the main river that Lindsay, Wonder and Warren creeks flow into today. The “improved” 2-lane US 30 of the 1940s had become today’s four-lane freeway by the early 1960s.

Coming Full Circle: Restoring Warren Falls

Since the mid-1990s, ODOT and the Friends of the Historic Columbia River Highway have worked to restore, replace and reconnect Samuel Lancaster’s magnificent old road. In some sections, the road continues to serve general traffic, though most of the restoration focus is on re-opening or re-creating formerly closed sections as a bike and pedestrian trail.

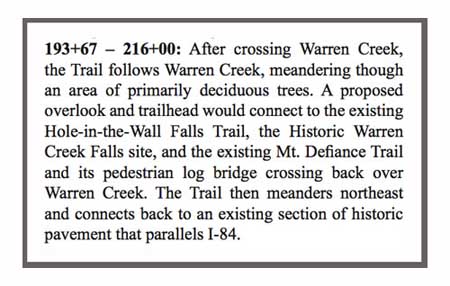

The trail segment in the Warren Falls vicinity is now entering its design phase, and is slated for construction as early as 2016, commemorating the centennial of Lancaster’s road. Though initially excluded from the plan, the restoration of Warren Falls is now shown as a “further study” item — a step forward, for sure, but still a long way from reality. The plan does call for an overlook of both the historic Warren Falls and Hole-in-the-Wall falls (shown below).

(Click here for a larger view of the trail plan)

There are three key reasons to restore Warren Falls now:

1. Funding is Available: The nexus for incorporating the restoration of Warren Falls into the larger trail project is clear: the trail project will require environmental mitigation projects to offset needed stream crossings and other environmental impacts along the construction route. Restoring the falls and improving fish habitat along Warren Creek would be a terrific candidate for this mitigation work.

2. The Right Thing to Do: Restoring the falls is also an ethical imperative for ODOT. After all, it was the former Oregon Highway Department that diverted Warren Creek, and therefore it falls upon ODOT to decommission the diversion tunnel and restore the falls. Doing this work in conjunction with the nearby trail project only makes sense, since construction activity will already be occurring in the area. Most importantly, it also give ODOT an opportunity to simply do the right thing.

Ain’t no way to treat a lady: the obsolete Warren Creek diversion tunnel is not only a maintenance and safety liability for ODOT (photo by Zach Forsyth)

3. Saves ODOT Money: Finally, the restoration makes fiscal sense for ODOT. The Warren Creek diversion tunnel is still on the books as an infrastructure asset belonging to ODOT, which in turn, means that ODOT is liable for long-term maintenance or repairs, should the tunnel fail.

The tunnel also represents a safety liability for ODOT, as more rock climbers and canyoneers continue to discover the area and actually travel through the tunnel. Decommissioning the tunnel and diversion would permanently remove this liability from ODOT’s operating budget.

Not good enough: excerpt from the HCRC restoration mentions the “Historic Warren Falls site”, missing the opportunity to restore the falls to its natural state.

How can you help restore Warren Falls? Right now, the best forum is the Historic Columbia River Highway Advisory Committee, a mostly-citizen panel that advises ODOT on the trail project. A letter or e-mail to the committee can’t hurt, especially since the project remains a “further study” item. You can find contact information for the committee on the HCRH page on ODOT’s website.

But it is also clear that Oregon State Parks will need to be a project partner to restore Warren Falls. The best way to weigh in is an e-mail or letter to the office of Oregon State Parks & Recreation (OSPRD) director Tim Wood. You can find contact information on the Oregon State Parks website. This is one of those rare opportunities where a few e-mails could really make a difference, and now is the time to be heard!

_______________________________________

Special thanks go to Kristen Stallman, ODOT coordinator for the HCRH Advisory Committee, for providing a wealth of historic information on the Warren Creek bypass project.

To read Oral Bullards‘ 1971 article on Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, click here. Though largely accurate, note that Bullards’ article is based on interviews of ODOT employees at the time, and not the original project files that were the basis for this blog article.

Next: a simple, affordable design solution for restoring Warren Falls!