The ancient Whitebark pines on Gnarl Ridge have managed to dodge wildfires for centuries through their rugged isolation, but can they survive our wilderness campfires?

Fire season was off to an ominous start this year with the Rowena and Burdoin fires sweeping across hundreds of acres of oak and pine savannah in the Gorge, destroying several homes. Yet, these early fires were a bit of an anomaly. Thus far, at least. We enjoyed a healthy, lingering snowpack in the Cascades this summer, and despite a late-August heat wave and the fires currently burning in sagebrush country east of the mountains, we’ve had a mostly cooler summer that seems more like 1980s than our overheated summers of today.

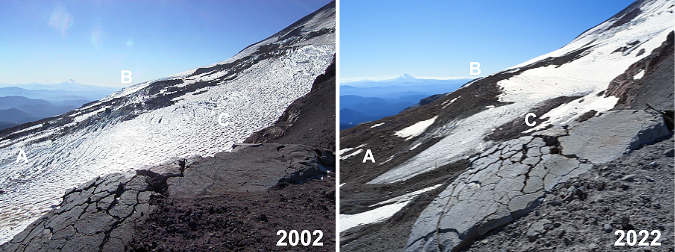

I’ve pointed this out to a fair number of younger hikers on the trail this summer while crossing rejuvenated snowfields on the Timberline Trail in early August. Until sometime around 2000, when the effects of climate change seemed to be visibly escalating, this is what summers were like here: a three-month drought with a couple heat waves, to be sure, but mostly moderate temperatures and even a few wet summer storms to break up the dry spell.

Our unexpected respite from extreme heat this year could also blunt the severity of our annual wildfire season, though it bears remembering that some of our most destructive firestorms have happened in September.

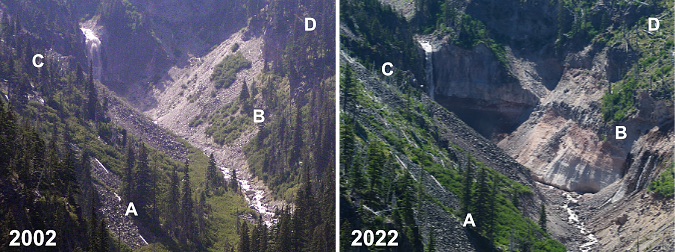

Not out of the woods with our fire season, just yet. The human-caused Riverside Fire started on September 8, 2020 and eventually burned 138,000 acres of the Clackamas River basin over the following weeks, much of the burn hot enough to create ghost forests where nothing survived. This scene looking into the Whale Creek basin is one of those places.

If we do make it past this Labor Day weekend without catastrophic fires in the Cascades – the five-year anniversary of the catastrophic fires that swept through in 2020 — odds are good that we will have enjoyed an unearned break this year in an otherwise non-stop era of major wildland fires. The emphasis should be on unearned, however, as we’re not making nearly enough progress in achieving a sustainable balance of healthy, beneficial fires in our forests.

Instead, we’ve catapulted from a century of unhealthy fire suppression and unsustainable forestry into the unhappy payback: a modern era of destructive, catastrophic fires fueled by the combined effects of fire suppression and overcrowded clearcut plantations in a rapidly warming climate. Add in a climate-denying administration in Washington DC that seems bent on somehow turning our collective clock back to 1955, and we’re losing ground fast on what otherwise could be a manageable crisis.

So, yes. There’s plenty of room for frustration and discouragement with the current state of affairs. But there are also encouraging signs that a return to more enlightened times has already begun, and the pendulum is beginning to swing toward science sustainability, once again. With that in mind, and in the spirit of “planning for good times during the bad”, this piece focuses on simple actions that we could take locally to help slow some of the momentum of a wildland fire cycle that is burning our forests faster than they can recover.

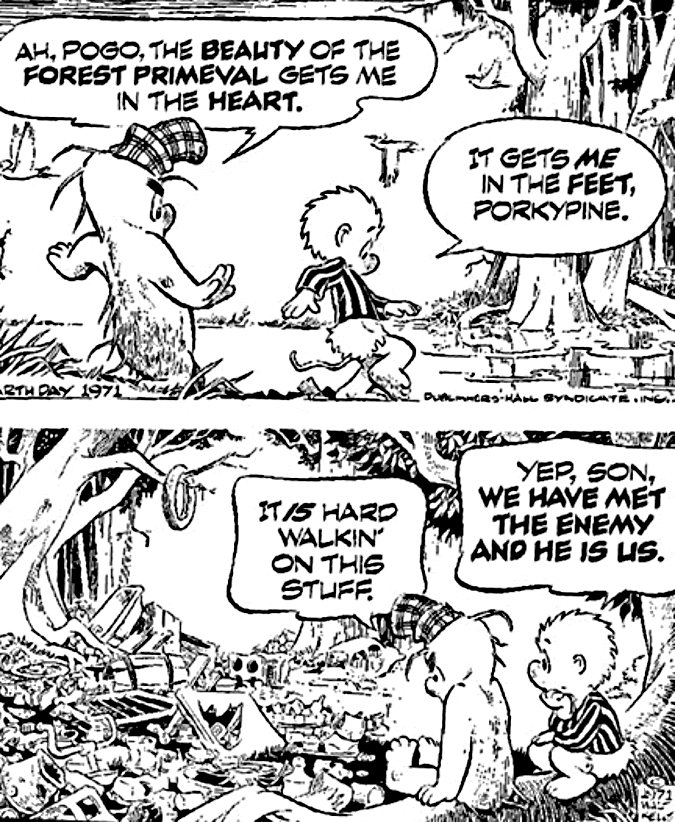

“We have met the enemy….”

You would be hard-pressed to find anyone under the age of 40 who knows what the “Sunday funnies” is (or was), much less Walt Kelly’s wise possum named Pogo. On the first Earth Day in 1970, Kelly produced a poster with the now-famous “we have met the enemy and he is us” strip, a play on a lesser-known military quote dating back to the War of 1812. Pogo’s version resonated, and Walt Kelly repeated it in this strip published on the second Earth Day, in 1971:

Pogo was right…

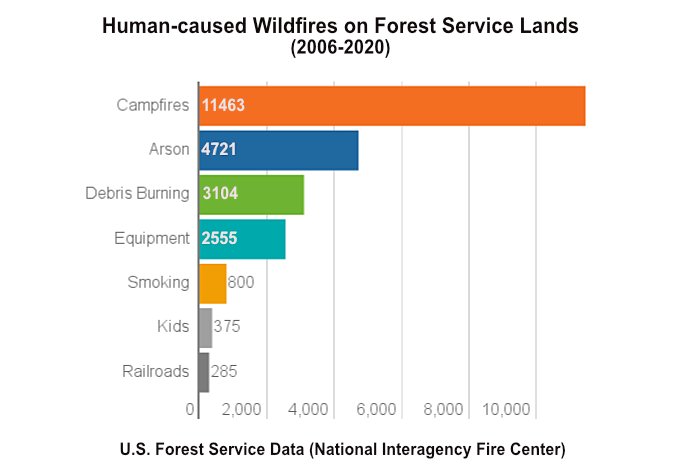

We’ve made real progress on environmental pollution since then, but Pogo’s observation could easily apply to our current wildfire crisis. Here’s a stunning statistic: research from the U.S. Forest Service in 2020 estimated that nearly 85 percent of wildland fires are caused by humans! That’s obviously an unacceptable number. The list of human causes? Campfires and debris burning are at the top of the list, followed by sparks from heavy equipment, fireworks and discarded cigarettes (arson is surprisingly high on the list – something to research for a future article?)

Campfires are the overwhelming human cause of wildfires

On our public lands, debris burning (as in logging slash) and sparks from heavy equipment mostly fall into the realm of logging and road construction, off-road vehicles and gas chainsaws used for firewood gathering. If you narrow the focus to human-caused fires that begin in our protected wilderness and backcountry areas, the list becomes much shorter: campfires, discarded cigarettes and (rarely) fireworks.

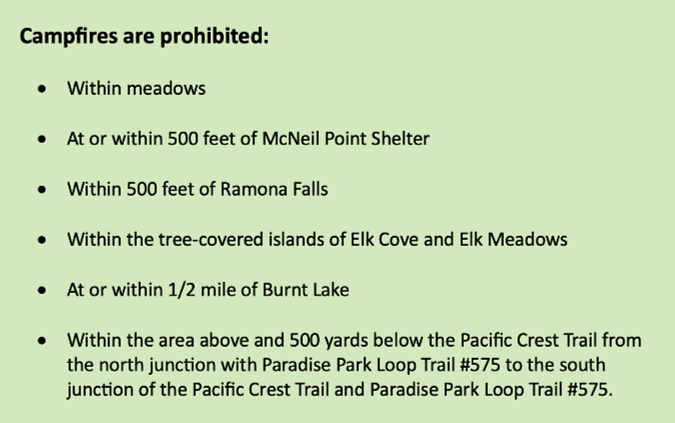

Narrowing a bit further to something we can tackle right here in WyEast Country, this article will focus on campfires within the protected Mount Hood Wilderness, and the surprising lack of restrictions on them. Few even know there are restrictions, but if someone were inclined to look it up, the list of places where campfires are prohibited on Mount Hood is puzzling, at best. Here’s the complete regulation:

Mount Hood Wilderness regulations on campfires (USFS)

First, some context: TKO’s Wilderness Ambassadors are counting in excess of 300 people heading to Paradise Park on the Timberline Trail each day on summer weekends this year – and that’s just one of the gateway points into the wilderness. Even if you assume that some meaningful share of the tens of thousands who enter the Mount Hood Wilderness are aware of campfire restrictions, these rules still seem random and confusing.

How would the average person know how far “500 feet from the McNeil Point Shelter”, or a “half-mile from Burnt Lake” is? What’s a “tree-covered island” versus a grove of trees at Elk Cove and Elk Meadows? The last rule is especially puzzling, though it seems to describe a near-total ban at Paradise Park. Add in the ever-shrinking number of Forest Service rangers available to patrol the Mount Hood Wilderness, and it’s hard to believe these restrictions are having any real impact as written, however well-intended.

Making the case: Protecting the wilderness experience

Though seemingly random, the places on Mount Hood called out in the campfire ban is instructive. These are all heavily-visited places where the increased wildlife risk of campfires is compounded by a degraded wilderness experience. It’s a compelling argument that anyone who has visited these places over time can testify to, as the human impacts are all-too apparent in each of the spots listed – and getting worse.

Once the cutting starts, it’s hard to stop. This butchered Whitebark pine had the misfortune of taking root near the Cooper Spur Shelter, perhaps before shelter and Timberline Trail even existed. It was still living as recently as 2020 (when these fresh cuts had been made), even as novice hikers continued hacking it apart for firewood too green to even burn

That’s why impacts on the human experience are a great starting point in making the case for a more effective, comprehensive campfire ban within the Mount Hood Wilderness. After all, much of the wilderness is very heavily visited, and many other popular spots face the same pressures as those few included in the current campfire ban. If visible impact from heavy use is the criterion, the Forest Service has simply lagged behind in adding to this list.

So, where to start in expanding the list? How about the entirety of Elk Cove and Elk Meadows, not simply the “tree islands”? And what about Cairn Basin, Eden Park and WyEast Basin? Or the rest of the Timberline Trail corridor for that matter? If you were to add every spot along the trail where campsites overflow with backpackers each summer, the dots on the map would quickly merge, making the case for a total ban. It’s simply too complex to describe or enforce a nuanced campfire ban with today’s widespread visitor pressure across so much of the Mount Hood Wilderness. Everything inside the wilderness boundary deserves this protection.

Making the case: A rogue’s gallery of wilderness campfires

I’ve lost track of how many ill-conceived campfire rings that I’ve decommissioned within the Mount Hood Wilderness over the years, but it is an ongoing and increasingly frustrating task. Most of these were not strictly banned under the Forest Service restrictions described above, but they very clearly violated basic “leave no trace” ethics. Worse, they were typically left smoldering, almost always because they had been built in a place too far from a water source to be safely extinguished. So, the campers simply walked away, leaving the seeds for a human-caused wilderness fire to chance. This rogue’s gallery is a sampler of what we are up against:

Not even a fire ring here, just a campfire built on top of the underbrush and forest duff layer along the Newton Creek Trail. It’s dumb luck this fire didn’t spread – likely due to fortuitous wet weather arriving that fall. Note the half-burned limbs left in the pit – how long did they smolder before the rains put this fire out?

This fire had been built on top of Bald Mountain, more than a mile from the nearest water source. It is typical of new campfires in the Mount Hood Wilderness. Lacking a saw, campers simply burned the ends of uncut logs and limbs, often several feet in length. With no fire ring, even the small limbs are spilling out of the campfire, in effect creating lit fuses for this fire to spread to the dry forest duff in all directions – as it already had when I took to photo. The half-burned stump adds to the risk, as it could smolder for days without being properly extinguished.

Another new firepit that had been recently built on a dry ridge top on the east side of the mountain, more than a mile from any water source. It was left smoldering, along with burned trash and (circled) cigarette butts that weren’t even dropped into the fire pit – checking two boxes for this fire on the list of most common causes

Amid the half-burned wood and charred foil, fire has a small orange flag you might have seen in heavily used fire pits during fire season…

…upon closer inspection, they turn out to be temporary bans put in effect during extreme fire risk. Placing these requires intensive wilderness staff capacity, though, and with no clear penalty identified for violators, are they even be heeded?

As some of these detailed captions show, new fire rings usually betray their builders. Almost aways, they contain burned foil, cans and melted plastic that a seasoned, knowledgeable backcountry visitor would never leave behind. Half-burned (and often green) firewood is the other giveaway, usually chopped with a hatchet that few experienced hikers would carry. They are also typically built on top of the flammable forest duff layer, instead of an area cleared to bare, mineral soil.

Smoldering, abandoned campfires don’t always put out a lot of smoke, even when they’re still very hot. This video is from a fire left burning in the Badger Creek Wilderness in the middle of August, far from any water source. Doubly frustrating was using much of my water supply on that hot day to put out a careless campfire…

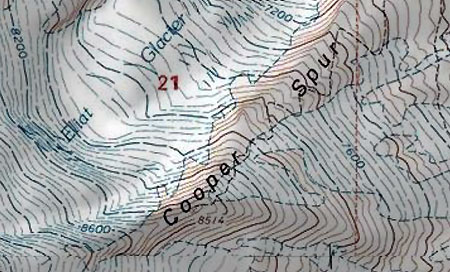

The next photo set in this rogue’s gallery is a case study of the historic Cooper Spur stone shelter on the Timberline Trail, where misguided campfires are a recurring problem. The shelter draws regular overnight campers who, in turn, have built several rock wall windbreaks around tent sites. Not exactly “no trace”, but also not unusual on the mountain. In this case, they must also be viewed in the context of being next to a man-made stone shelter. The hand of man prominent here, however rustic.

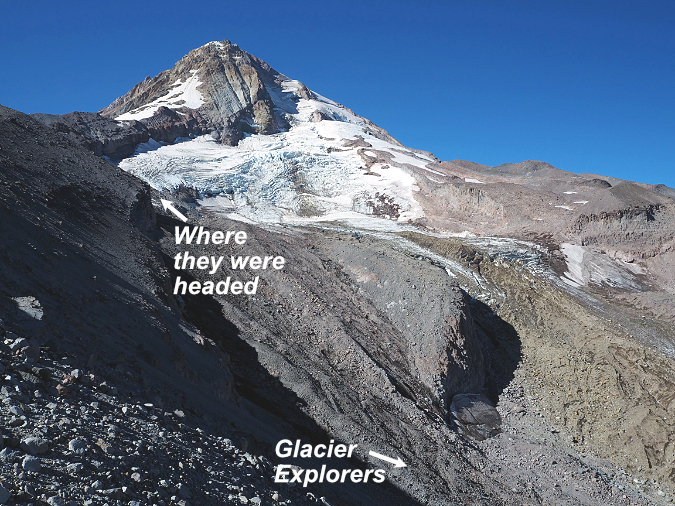

Camping among the rocks at the Cooper Spur shelter has become increasingly common in recent years, thanks in large part to social media, and helping to drive the increase in campfires here

However, there is no water source anywhere near the shelter, so it’s not an ideal camping spot. It’s an even worse place to build campfires. Most campers at the shelter do abide by this obvious ethic, but the few who don’t leave a permanent record of their visit for all who follow in this very popular place. That’s because, beyond the lack of water to reasonably extinguish a fire, there’s also a lack of firewood… except for the federally-listed, threatened Whitebark pines that cling to life here, at nearly 7,000 feet elevation.

I’ve decommissioned many campfires here since unofficially adopting some trails in the area nearly 25 years ago. All of these campfires were perfectly legal under the current Forest Service rules, but also completelyunethical from a “leave no trace” perspective. They also fail simple common sense, given the obvious lack of a nearby water source to put them out.

To put a face on this ongoing struggle, here are some of the rogue campfires that I’ve decommissioned at the Cooper Spur shelter in recent years:

This fire ring has been rebuilt against a boulder, directly in front of the shelter – a favorite location for the campfire builders

A closer look at the 2014 fire ring. The boulder is charred from many fires built here, but the rest of this ring was new, as you can see by the mostly uncharred, smaller rocks

Fuel piled next to the 2014 fire ring includes green limbs pulled from a nearby Whitebark pine, typical signs of a novice

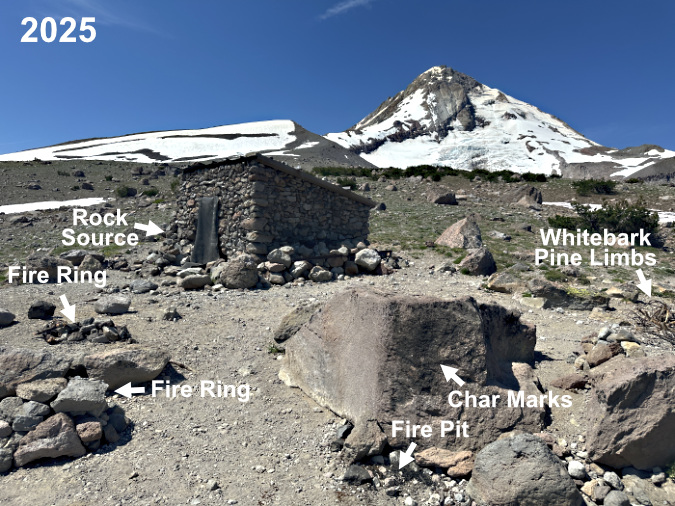

In the intervening years since these photos were taken in 2014, I’ve disassembled and decommissioned this fire ring repeatedly, as the charred boulder seems to attract ever more campfire building at this spot. However, this year things seemed to escalate sharply. This was the scene in late July:

Three campfires – within a few feet of one another? The fire ring on the far left was built in the middle of the trail, the one below on the left was built (once again) against the same boulder shown in the 2014 photos and the fire pit in the lower right was also new – the first in this spot. A large stack of Whitebark Pine limbs, both dead and living, are piled over on the right

A closer look at the new ring built in the middle of the trail shows half-burned Whitebark pine limbs and an attempt to extinguish the fire by piling rocks on top.

A closer look at the new ring shows the rock source to be the recently collapsed corner of the Cooper Spur Shelter – those are mortar traces attached to the rock in this photo. Pure vandalism to use these rocks before they could be to repair the shelter, of course

Decommissioning all three of these fire rings at the Cooper Spur shelter meant carrying at least a dozen gallon-size ziplock bags of (cold) ashes to dump in a discrete spot, moving all of the visibly charred rocks from the area and covering up what was left with a light dusting of loose gravel. However, the char marks left on the large boulder in this newest fire location will be there for many years to come, likely encouraging more fires here so long as they are legal.

This was among the charred Whitebark pine logs scattered from the three fires, apparently in an attempt to put the fire out? This log was cut with a hatchet, another telltale sign of a novice camper

What’s left of this Whitebark pine near the three new fire pits at the shelter shows signs of limbs being sawed, chopped or simply broken off. The stumps still have their bark, so it’s unclear if this was a living tree when it was targeted for firewood

While it has been a frustrating rinse-and-repeat cycle to continually undo these fire rings, it’s also informative. They point to wilderness visitors who require very simple, understandable and enforceable regulations. Even if the area around the shelter were added to the current list of banned places on the Forest Service list, the campfires would almost certainly continue, given the lack of awareness of where fires are prohibited in the wilderness.

Making the case: Current rules aren’t working

In researching this article, I spoke to several seasoned hikers who have been visiting the Mount Hood Wilderness for many years. Even among this veteran cohort there was tremendous confusion and misinformation about the restrictions that do exist, or even where to find them. Some were adamant that campfires were already banned “above the Timberline Trail”, while others believed the ban was “above the timberline”. None could name all of the place-specific bans described in the actual policy, and most could only name one or two. This level of misinformation among the most experienced hikers bodes poorly for the thousands of less-savvy visitors to the wilderness each year might know.

Today’s wilderness hikers on Mount Hood rely more on social media and third-party phone apps for their trail information than on official web content from public agencies, making it increasingly challenging to communicate rules and restrictions

The lack of awareness and understanding of the existing campfire ban is easy to diagnose. First, the official Mount Hood National Forest website is labyrinth, and it’s especially tough to navigate if you’re looking for recreation information. When I Googled “Mount Hood Wilderness”, only the unhelpful Mount Hood National Forest home page and generic “recreation” page showed up in the top 20 search results. Both are dead-ends.

The crucial link for wilderness information (including campfire regulations) is found elsewhere on the website, on a page describing all of the wilderness areas within the national forest – a page Google did not find with a search for “Mount Hood Wilderness.” From this page, the link to information on regulations for the Mount Hood Wilderness is buried in a text blurb that contains a link to this external website describing the campfire policy.

Even a specific Google search for “Mount Hood Wilderness Regulations” takes you to the generic wilderness page for all wilderness areas, where you would still need to track down the buried link to the external page that actually lists the regulations. Few will ever find this information, unfortunately – including Google’s search engine. Google’s AI-powered search provided an even more confusing result, reporting a complete ban on wilderness campfires (!) followed by a partial mention of the actual policy (only for McNeil Point and Ramona Falls):

Google AI not so intelligent when it comes to finding USFS regulations…

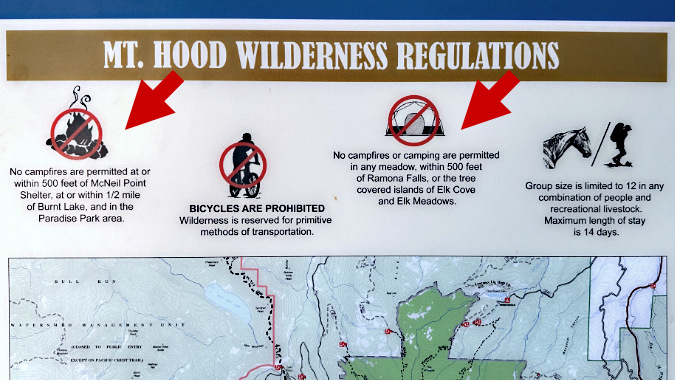

So, the internet isn’t much help in tracking down the existing campfire regulations. However, the current ban is clearly described at wilderness trailheads around Mount Hood – if you look closely – along with general guidelines on wilderness ethics, including no-trace ethics campfires.

These are the trailhead signs at the Cloud Cap trailhead, the entry point for the Cooper Spur Shelter, and the standard signboard format for most wilderness trailheads on Mount Hood:

There’s a lot of information at Mount Hood’s wilderness access points. Look closely at this sign at the Cloud Cap trailhead and you might find the limited restrictions on campfires (circled)…

…and a closer view of the campfire restrictions from the above wilderness trailhead sign. The wording here is simplified from the official regulations, yet still quite nuanced for visitors unfamiliar with the wilderness

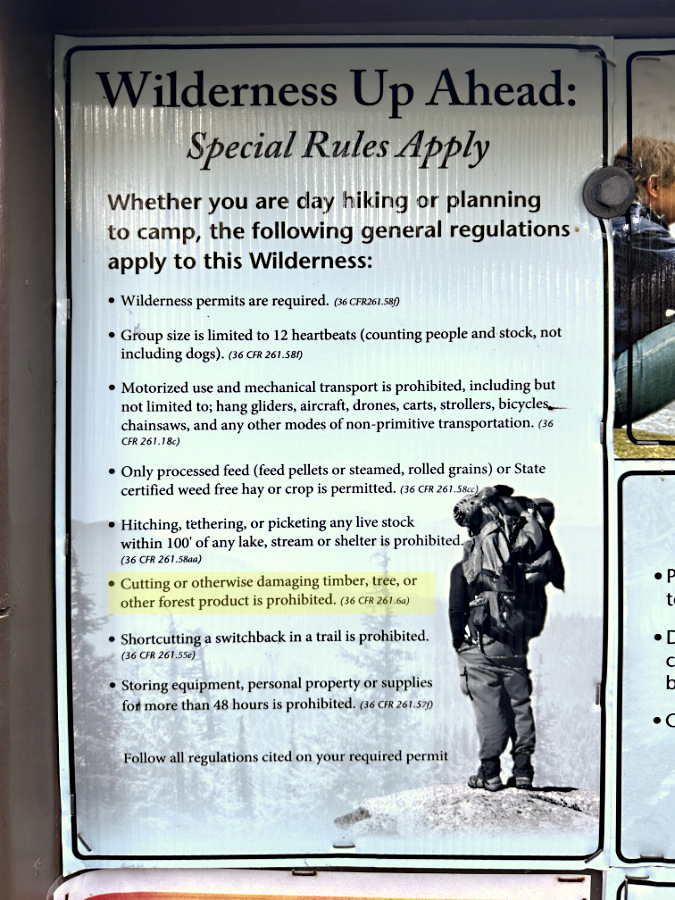

A second sign at the Cloud Cap wilderness trailhead provides still more information for visitors. The two arrows point to additional info on campfires…

…this enlarged view of the inset on the upper right calls for “minimizing” (highlight added) campfire impacts under the Leave No Trace (LNT) principles…

…and the inset on the left side of the second trailhead sign lists special rules for wilderness, including “cutting or otherwise damaging timber, tree or other forest product” (highlight added)

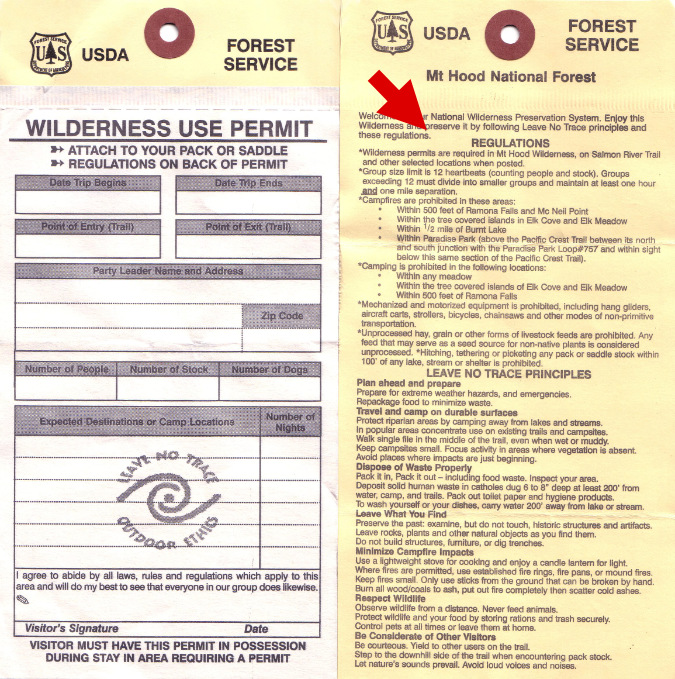

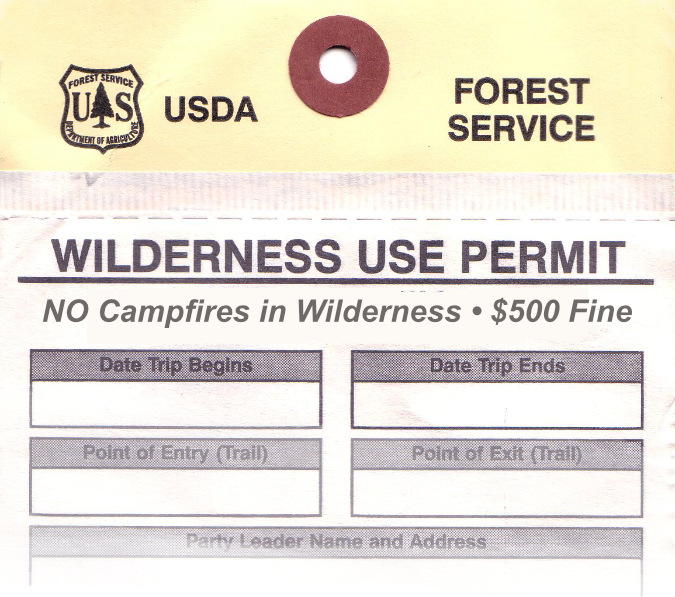

The current, limited campfire ban is also posted on the back of required wilderness permits, which are required at the Mount Hood Wilderness entry points (except this year, unfortunately, due to Forest Service staff cuts):

There it is! The red arrow points to the Mount Hood Wilderness regulations printed in full on the back of the permit

A closer look at the permit shows a nearly complete version of the existing, limited campfire ban within the Mount Hood Wilderness, albeit slightly simplified from the online, official version

So, the regulations are certainly available enough where it matters – at the trailhead. But the fact that so few know or understand them suggests they aren’t really being read by wilderness visitors – whether on the entry signboards or on the back of permits. That’s likely a case of information overload (there is a lot to read on these signs) and human nature (does anyone really read instructions before assembly..?) Add the complexity of the regulation, and it translates into a policy that is not only too limited in its geographic scope, but also in its effective communication to wilderness visitors.

Making the case: Protecting human life and property

Do the risks and impacts that campfires present at the Cooper Spur Shelter and elsewhere in the Mount Hood Wilderness warrant a total ban on campfires? Thirty or forty years ago, my answer would have been “no”. But the current state of our forests and changing climate doesn’t leave us the luxury to be romantic or sentimental about campfires.

Cloud Cap Inn covered in red fire retardant during the Gnarl Fire in 2008. This historic, priceless 1889 gem narrowly survived the event (USFS)

Cloud Cap area transforming into a massive ghost forest of bleached snags in 2010, two years after the Gnarl Fire

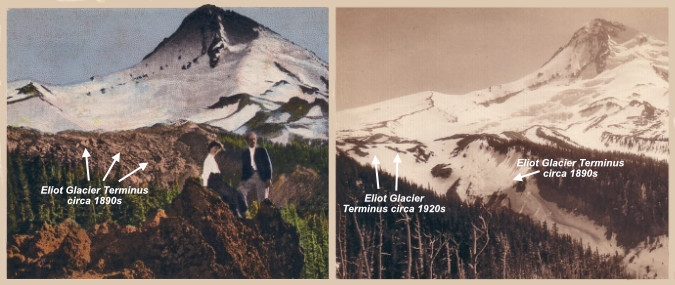

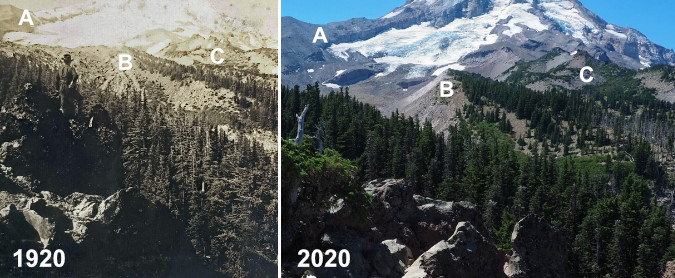

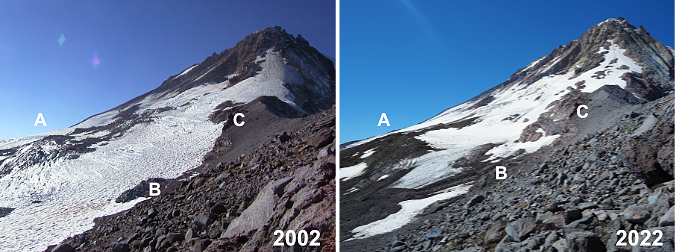

We’ve seen a string of three major fires in the Mount Hood Wilderness in recent years that have completely altered the forests on the north and east slopes of the mountain: the Bluegrass Fire (2006), Gnarl Fire (2008) the Dollar Lake Fire (2011) all burned hot across thousands of acres of subalpine Noble fir, Mountain hemlock and Western larch at an unsustainable pace, leaving large expanses of ghost forest that are only beginning to regenerate today.

None of these fires were human-caused, surprisingly. But there’s little comfort to be found there, given the number of people who visit the wilderness each year – and the number unattended, smoldering campfires they leave behind.

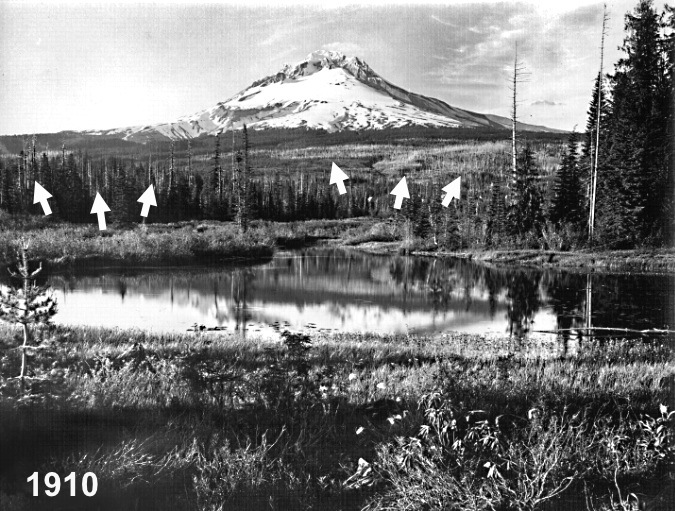

It’s also only a matter of time before similar wildfires return to the south and west sides of the mountain, where a century of fire suppression has left these forests primed for a major fire. And the risk to property and human life on the south side of the mountain is far more significant. Early photos like those below show the extent of the most recent fires to rage through today’s Government Camp area in the decades before the completion of the Mount Hood Loop Highway in the 1920s, and the subsequent flood of ski resorts, Forest Service cabin leases and homes on private land that followed.

This view of the Government Camp area from Multorpor Fen before much development had occurred on the mountain. The arrows point to the ghost forests that marked widespread burns across what are now heavily developed ski resorts and private homes on Mount Hood’s south flank. After more than a century since these fires burned through, the south side of the mountain is primed for a major wildfire

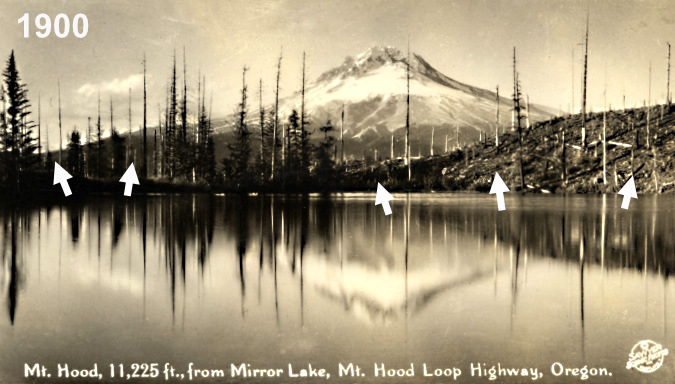

While the surge in recent wildfires on Mount Hood has focused on the east and north sides of the mountain, the west and south sides were the main focus of wildfires in the early 1900s. This view is of Mirror Lake in about 1900, when much of the area south of today’s US 26 had burned in the Kinzel fire

This later view of Mirror Lake from the 1920s shows little forest recovery – and the beginning of what is now more than a century of camping — and campfires

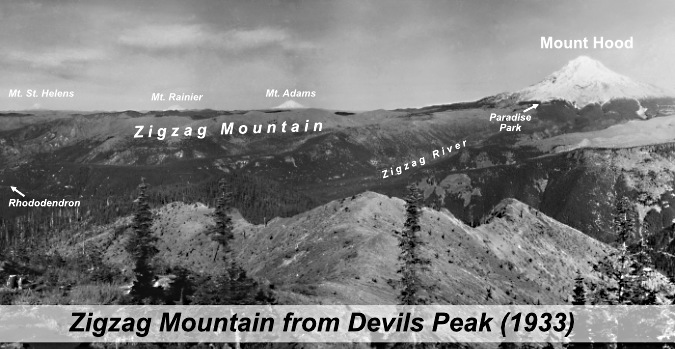

The risk to human life and property only grows as you move to the Zigzag Mountain arm of the wilderness. Zigzag Mountain comprises a complex of forested ridges and peaks that extends ten miles west from Paradise Park on Mount Hood to the community of Zigzag, where the Zigzag and Sandy River valleys converge. Zigzag Mountain and much of the surrounding area burned repeatedly in the early 1900s, long before there were thousands of people living in forest homes along both rivers and scores of businesses had located along this section of the Mount Hood Loop Highway.

The view from Devils Peaks in the 1930s looked much different than today. The peak, itself, had recently been burned over in the Kinzel and Sherar fires, while the area north along Zigzag Mountain was also burned in a series of very large fires in 1904 and 1910 – including the Burnt Lake Fire

[click here for a large version of the Zigzag Mountain infographic]

While it is inevitable that wildfires will someday sweep through these areas again, igniting one with an unattended, smoldering wilderness campfire doesn’t have to be the cause. And while the Zigzag Mountain portion of the Mount Hood Wilderness is less busy with visitors, the human and property risks from wilderness campfires here are far greater because of the proximity to developed areas immediately adjacent to the wilderness.

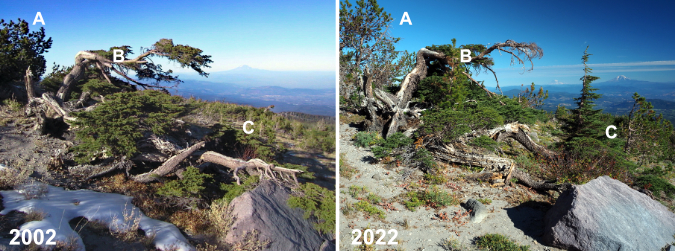

Making the case: Protecting the Whitebarks

Protecting human life and property is deservedly the driver in wildfire management, but on Mount Hood, the impact of wilderness campfires extends to our threatened Whitebark pines. I described both their significance as a keystone species and plight in this article several years ago. These are trees worth protecting.

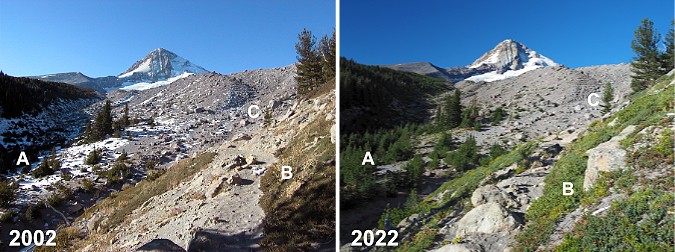

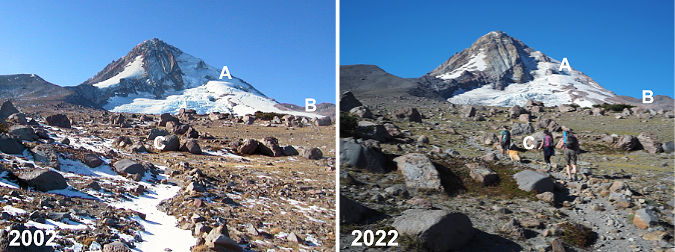

Their ability to thrive in extreme, high elevation environments is part of their secret to dodging forest fires. The ancient groves of Whitebark on the mountain are often so isolated and scattered in their alpine setting that fires racing through the more continuous subalpine forests far below have repeatedly missed them simply because they were out of reach from the flames.

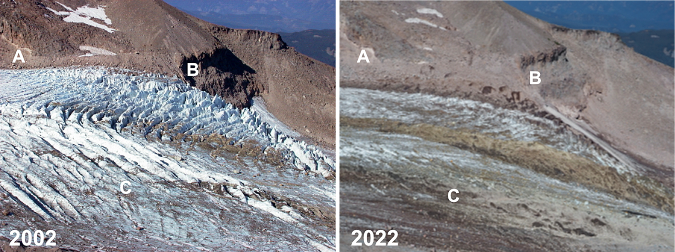

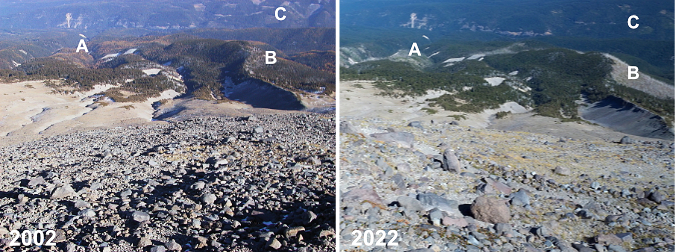

This advantage was borne out again with the recent fires on the east and north sides of the mountain, where the flames seemed to die out as they reached the tree line, well short of many of the ancient Whitebark groves. Their remote habitat is not out of our reach, however — or the impact of our campfires.

This unlucky Whitebark pine has been harvested down to a stump for firewood at the Cooper Spur Shelter

The campfire threat to Whitebarks comes from being hacked apart for scarce firewood this far above the tree line. However, Mountain hemlock and other subalpine species are continuing to spread upward in elevation in our warming climate, infiltrating the once isolated Whitebark Pine groves, and thus increasing their exposure to wildfire.

Mature limbs from Whitebark pine in a large fire pit on the summit of Lookout Mountain, in the Badger Creek Wilderness

There is also an important aesthetic argument for caring about our Whitebarks. While you can’t place a dollar value on the visual and emotional impact of seeing a massive, ancient Whitebark pine in the wild, for most of us it is an awe-inspiring sight. Their contorted shape and especially their bleached bones tell a story of remarkable survival – but they can also provide senseless firewood to a few campers who don’t know any better.

These ancient Whitebark pine skeletons are as beautiful and dramatic as they are vulnerable: the fire pit in the previous image is just a few yards beyond this grove

Beyond our human impact on these trees, Whitebark pine are experiencing a massive die-off across the West from a invasive diseases, insect infestations and worsening drought episodes driven by climate change. This has led them to be federally listed as a threatened species. Given their plight and importance, Whitebark pine may be the best reason for a total campfire ban in the Mount Hood Wilderness.

Whitebark pine along the Timberline Trail selected for seed harvesting in a Forest Service project to help save the species

Seed collection bags on one of Mount Hood’s selected Whitebark pines for genetic research

Since the 1990s, scientists at Mount Hood National Forest have been part of the national recovery effort for Whitebarks, where seeds are being collected from disease resistant trees for propagation to help replace groves where widespread die-offs have occurred in recent years. For more information on this effort, check out the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation, a leader in the effort to rescue this unique species.

All of these arguments – the threats to our remaining forests, to human life and property and to the Whitebarks — bring me to the conclusion that now is the time for a complete ban on campfires within the Mount Hood Wilderness. No exceptions. Just a simple, understandable and permanent ban.

Making the case: How it’s done elsewhere

The Park Service bans all wilderness fires within Mount Rainier National Park, a model for Mount Hood (NPS)

No doubt the Forest Service would be wary of doing this, but there is already precedent within our national parks. Mount Rainier National Park bans campfires in all backcountry areas, the equivalent of wilderness there. Many western national parks have complete bans seasonally every summer – including in their campgrounds – often beginning as early as late May or early June. These include North Cascades, Olympic, Crater Lake and Mount Rainier national parks in the Northwest, and several other national parks across the country.

Wilderness campfires are completely banned at Rocky Mountain National Park (NPS)

Kings Canyon National Park has a limited prohibition, banning campfires only in alpine areas above 10,000 feet – an abstract metric that would be unlikely to register with newbie hikers most prone to building campfires in these areas (NPS)

Beyond the goal of simply reducing the risk of human-caused fires, the simplicity of complete campfire bans helps compensate for the inevitable lack of enforcement capacity in wilderness areas, whether in national parks or forests. Unattended or dangerously built campfires aren’t there because people want to start a wildland fire, they’re simple a result of ignorance of the risks they present.

The Park Service approach is a simple, direct, teachable way to serve both outcomes – to prevent the risk of human caused fire, and to educate the public on the reality of the risk. A total ban is at least something that can be understood and thus has a chance of being reasonably self-enforced.

Making the case: Taming our inner caveman…

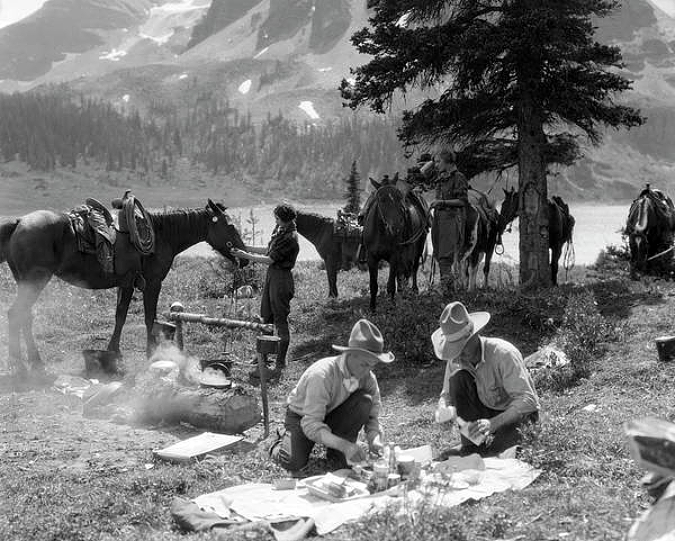

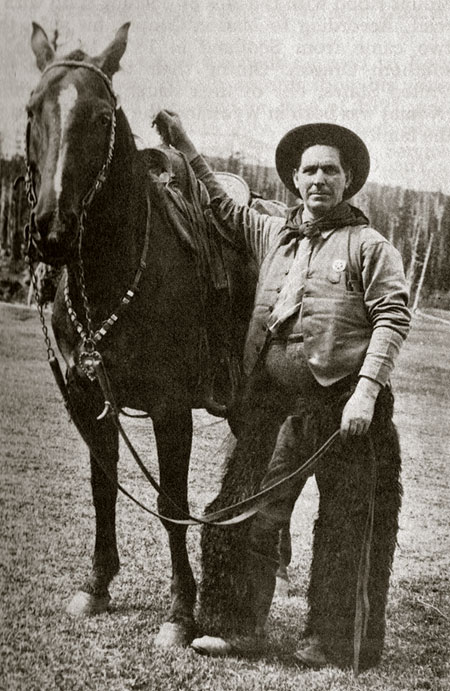

Heat, light and cooking, all in one. We do seem to retain a primal connection to fire (…that looks to be one of my ancestors on the left, by the way – holding a very large marshmallow stick…)

There’s an undeniable romance with campfires that gives pause to land managers like the Forest Service when it comes to pre-emptively regulating them. Yet, human-caused catastrophic wildfires in WyEast Country in recent years in places like the Columbia River Gorge in 2017 (infamously caused by teenagers with fireworks) and the massive Clackamas Riverside Fire in 2020 (apparently caused by a campfire) have begun to change that posture, albeit very gradually.

For the past few decades, the focus of culture change with wildfire has been on a better public understanding of the benefits and necessity of fire in our forest. It’s an essential piece of changing our attitudes, especially since prescribed burns continue to be controversial — despite their proven value. However, letting go of campfires as a ritualistic part of the outdoor experience has not been directly confronted by the Forest Service – yet.

The mythology of the American West in the 1800s continues to be another part of our romance with campfires. These cowboys are preparing their morning Double Caramel Frappuccino with freshly baked Petite Vanilla Bean scones…

The utilitarian purpose of campfires for cooking is long gone. For wilderness backpackers, alternatives to a wood fire for cooking came in the early 1950s, when compact gas and alcohol stoves were first developed, based on portable military stoves. Today, the advantage of stoves for their simplicity, ease of use and certainty for cooking has made them standard practice for backpackers. And while it’s true that you can’t roast marshmallows or hot dogs over a portable gas stove, that’s what our developed campgrounds offer.

It is true that a fire can be a life-saving source of heat in a wilderness emergency, but so can proper clothing and shelter that are among the 10 essentials that every hiker should carry. And a rare emergency survival fire that might be warranted still represents a fraction of the impact and risk that not having any limit on campfires represents.

Our modern-day connection of campfires to the camping tradition began with the arrival of the automobile and developed roads into our public lands in the 1920s. Though early adopters hauled everything for their campsite in their Model T, developed public campgrounds with picnic tables and formal campfire pits soon followed. Campfires in developed campgrounds today are rarely the source of wildfires today, so they continue to provide a safe solution for campers looking for that S’mores experience

In the end, the most personally compelling case for a ban in our time may be the environmental impacts and risk of wildfires that campfires bring. People head for the wilderness to get away from the human-impacted world, and the despair and sense of loss that so many have shared from our recent, catastrophic fires in the Gorge and on Mount Hood underscore just how personal the connection to wilderness is. That’s a winning argument for a ban that most would understand.

Wilderness is special, and this is where a broader understanding of the ethics of wilderness campfires could begin. What not begin growing that awareness here on Mount Hood?

Making it Happen…

The good news is that a national forest supervisor can make this happen with the stroke of a pen, as these policies are made at the local level. The most direct approach would begin with signage at Mount Hood’s wilderness trailheads, with both regulatory and interpretive messages. For those who take the time to read the signboards (and we salute you!), the messages already posted could be adapted to make the interpretive case for a campfire ban.

However, if the goal is to get the message across to the majority of visitors, a blunt, direct and unavoidable approach is warranted. Like this sign – which, for the record, is not a real Forest Service sign (yet):

Keep it simple and direct. To ensure visibility, a sign like this should be posted away from the information overload of the main signboards and directly below the wilderness boundary markers that that are typically the last sign a hiker passes when entering the wilderness. Again, this example is from Cloud Cap, where you can see the wilderness marker in the distance, just up the trail:

Make the campfire ban (and associated fine) the last thing hikers see as they enter the wilderness, where it might just catch their attention…

To reinforce this very direct approach, the same message could be added to the front of the wilderness permits to better catch the eye of those of us (ahem) who are clearly not reading the back of the form:

…and make it the first thing they see when they complete their wilderness permit

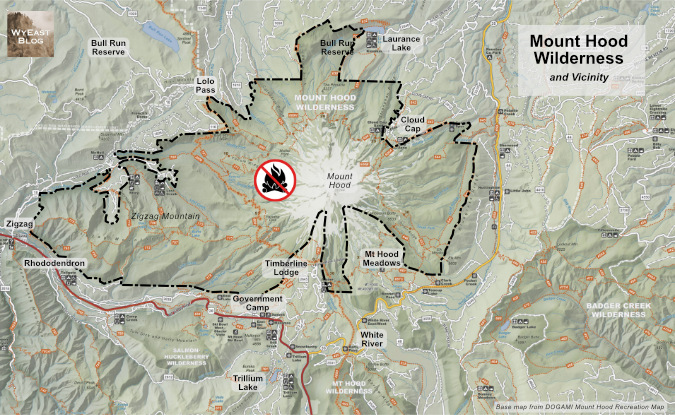

Where would this ban apply? Everywhere inside the Mount Hood Wilderness boundary shown below. The wilderness has been expanded several times since the “Mount Hood Primitive Area” was first designated as wilderness in 1964. This is the current boundary where the campfire ban would apply – and including a ban icon on maps like this could be still another helpful reminder for visitors:

The boundary of the Mount Hood Wilderness where the campfire ban should be enacted

[click here for larger view of the map]

While I’ve highlighted what most consider to be the Mount Hood Wilderness on this map, several nearby wilderness areas have been created or expanded since the 1980s, including the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness and Badger Creek Wilderness, as well as smaller pocket-wilderness additions at places like Twin Lakes and Tom Dick and Harry Mountain. Should these areas be included in the campfire ban, too?

My answer is no, at least for now. That’s because these areas are mostly less visited and – with the exception of the summit of Lookout Mountain in the Badger Creek Wilderness — don’t have a Whitebark pine population that could be impacted by wilderness campfires. Over the longer term? Yes, these areas should also be included, as we continue to grapple with the wildfire crisis that is unfolding in our forests.

Why it matters…

Ancient Whitebark pine just off the Timberline Trail on Gnarl Ridge

I’ll close with a photo of one of my favorite Whitebark pine ancients (above). It has likely been growing in this sandy flat near the crest of Gnarl Ridge for at least a couple centuries. And it therefore likely witnessed multiple eruptions of smoke and ash from Mount Hood in the late 1700s as a young tree, the last major eruptive period on the mountain.

This old survivor was just getting established here when Lewis and Clark opened the floodgates to white settlement, and thus far it has survived our arrival in the intervening 200 years. Because of its remote home on the mountain, it also survived the Gnarl Fire in 2008, and very likely other wildfires on Mount Hood’s east slope over the centuries. So far, it has also survived the bug and disease infestations attacking our Whitebark pine forests.

Constant sculpting of this ancient Whitebark pine on Gnarl Ridge from blowing sand and ice crystals prevents the it from oxidizing to grey before it is sanded away, continually revealing the underlying color of the wood

This old tree is also about 200 feet from a group of tent sites along the Timberline Trail. What it may not escape is some camper snapping off its ancient, gnarled limbs for firewood — or worse, a spot wildfire caused by an unattended campfire left burning here for lack of a nearby water source on this windy, exposed alpine ridge.

For me, helping these threatened survivors live another century so that future generations might see and be inspired by them is perhaps the reason of all for finally putting an end to our wilderness campfires.

_____________

Tom Kloster • August 2025

_____________

Postscript: I’ve noted this in recent articles, but it bears repeating: this piece is written at a time when the Forest Service, National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management are under siege from a hostile administration in an unprecedented, orchestrated and blatantly corrupt attack on our public lands. My intent is certainly not to pile on at a time when our public workers at these agencies need our support and respect.

However, I also accept the unfortunate reality that it will take many years to restore these organizations. In the meantime, we will need new approaches to protecting our public lands until we eventually rebuild the agencies charged with their management. This article is written in that spirit and in deep support for our public lands agencies.