Main page on the new WyEast Images companion blog

Finally! After months of tinkering, stalling, backpedaling, rethinking, reformatting, rebooting and a few late-night rants against the constant evolution toward more complexity of the WordPress plaform (that I use for this blog), I’ve finally started up a companion to the WyEast Blog that I have had in mind for many years. It’s called the WyEast Images Blog and it is completely dedicated to photos.

Why this and why now? Here are my motivations, in no particular order:

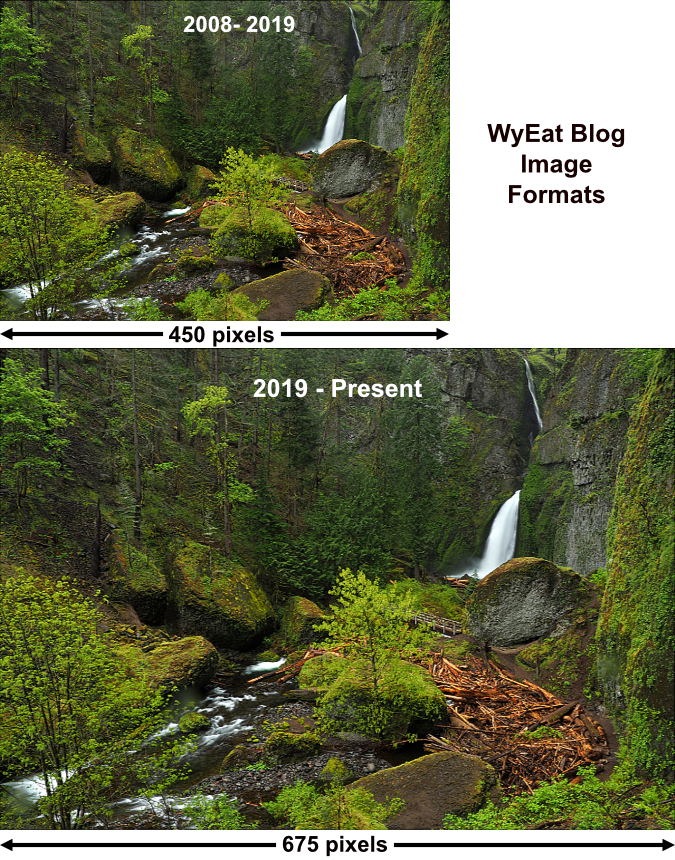

Image constraints: though I’ve periodically updated the blog template I use for the WyEast Blog, I’ve kept it tethered to the goal of easy reading on tablets, phones and e-mail, with an emphasis on fast downloads and small screen viewing. This has translated to relatively limited image size. The original format when I started the blog back in 2008 was especially constrained, with a maximum image width of just 350 pixels. At the time, the iPhone had barely been invented (in 2007) and the iPad had not arrived yet (it would come in 2010), so download speeds were the main driver behind those original, small images – most of us were still connecting up on low-resolution computer monitors via our phone lines in those days!

As handheld devices took over, the original 350-pixel scale worked pretty well for the screen size and resolution of those early devices, too. So, it wasn’t until 2019 that I finally updated the blog image format to fixed width of 675 pixels. While this is already smallish by today’s standards, it still looks very good on phones and tablets, in particular. Here’s a comparison of just how big a leap the change from 350 to 675 pixels was in terms of image size and resulting detail:

Original and current image formats for the WyEast Blog compared

Because the 675-pixel size is still working fairly well, I don’t see big changes coming for the WyEast Blog format on this front – if I can avoid it! Part of that is due to the legacy impact, as each time I upsize the template, the images in the original posts from 2008-2019 look increasingly like they had somehow shrunk in the wash of time (and many of these articles still get active views, surprisingly!)

Therefore, when I want include larger images (typically for maps and nerdy schematics) I end up linking to a separate file that can be viewed in greater detail. I’ve done this since the beginning with the “click here to see a large version” option for both faster overall downloading, but also because the compressed large versions don’t look that great when auto-scaled inline into the 675-pixel blog format.

This workaround has been fine for maps (and my nerdy schematics), where users can choose to open the large version and zoom in to great detail, or simply scroll past the link. However, it’s not so great for photos, and photos are my passion!

With photos, bigger really is better: Thus, the new, WyEast Images companion blog where the images are the focus (ahem!). Each post will include a single image at much larger scale with a few, hopefully succinct paragraphs providing context and significance of the image.

How much larger than images in the WyEast Blog? Images in the new blog are 1400 pixels wide, compared to just 675 pixels on this blog. Here’s another comparison of what that means for image size and resolution:

Image formats for the WyEast blog and new WyEast Images blog compared

The larger images do more justice to what I saw and felt out in WyEast Country than a small, inline image in a WyEast Blog post can offer. I also have thousands of images from a lifetime on the mountain and in the Gorge that I don’t get to share through conventional, story or issue-driven blog posts, so this is an outlet to simply enjoy these amazing places in our world.

For several years, I have been building up an archive of images on a proprietary photo hosting service (called Zenfolio) that I intended to use for this purpose, but it was clunky to administer, expensive and awkward for folks to browse if they were new to the interface. It just wasn’t working out. So, I allowed that subscription to lapse as of December 31 – which also happened to be my last day working before I retired! So, there are a couple of reasons for the “why now?” question I opened with. I finally had some precious time to get this up and running!

Supporting our photography professionals: along with the larger image format come some real reservations of publishing at this scale, as I know from my own experience that they will be vulnerable to being used without permission in the wild west that is the internet. That annoys me because, in my view, only photographers who make their living from the craft should be competing for the scarce dollars out there in the commercial market for photographic art.

I ‘m proud to count several of these talented folks as my friends, right here in WyEast Country, and they are already struggling to keep up with the torrent of “free” images that circulate on the web — largely without permission, much less compensation. The emergence of completely unregulated AI-generated imagery will only compound this problem.

This is why I am (and always will be) an amateur photographer, by definition. I never sell photos, with the caveat that I occasionally donate them for use by non-profits and sometimes public entities. To maintain this bright line, I’ve taken the added step of including a discreet signature to each image (the squiggly scrawl in example below) in the new blog to discourage re-use, along with a copyright line in each blog post – something I’ve never done on this blog, but will do in the new blog for the reasons I’ve just described. We’ll see how it goes!

I’ll keep it discreet, but the large images on the new blog will have a watermark signature

The goal of the signature is to simply to help me spot when images have been appropriated for a commercial purpose and remedy that – and hopefully to point the perpetrator to one of our fine area professionals to purchase a legitimate stock image that meets their needs.

Short reads: No surprise if you are a WyEast Blog reader, this is a long-format blog… and getting longer all the time! Therefore, the core intent of the new companion blog is to provide a side channel for you (and me) to cover WyEast topics in a text-light, image-centric format that celebrates the larger mission of the WyEast Blog: that Mount Hood and the Gorge are supremely special, and deserve better care and protection than what we give them. A simple photo can often make that case more powerfully than words are capable of.

Better Accessibility: You may have been tracking the accessibility movement on the internet in recent years, but the trend is strongly toward detailed captions for images so they may be enjoyed by visually impaired readers. Thus, each photo caption in the new blog will be followed by a detailed image description. This enhances the photo for any reader, too, as the description will often contain background information not immediately intuited from the photo.

Time travel: my personal photo archive of WyEast Country goes back decades, but I’ve also hoarded thousands of historic images that I’ll occasionally post for some real time travel. We already have the amazing Hood River History Museum’s Historic Hood River photo blog and photographer Gary Randall’s excellent “You know that you’re from ‘The Mountain’ if…” public Facebook group covering that beat, so historic posts on the new blog will be rare and hopefully complementary to these other forums when I put them up.

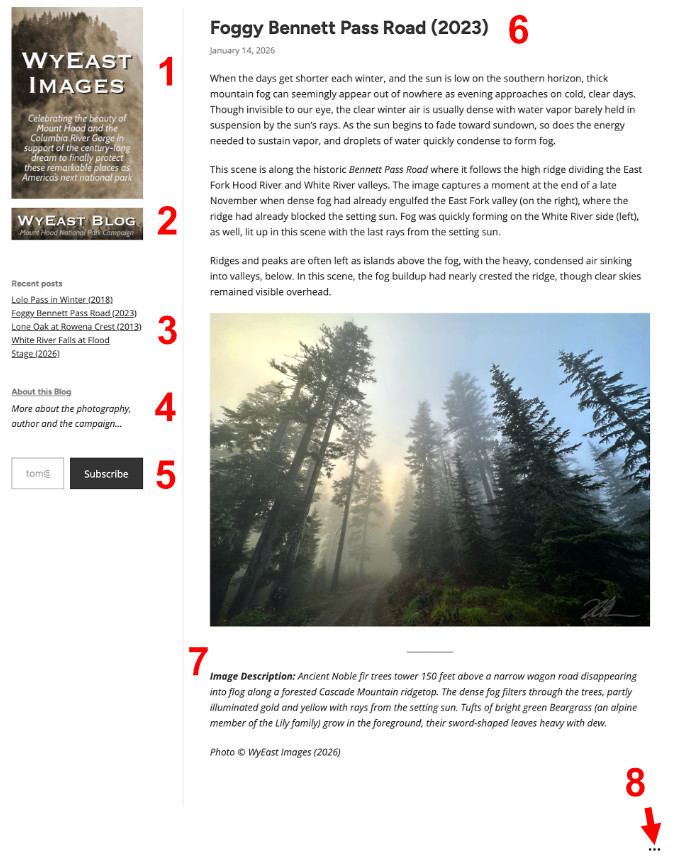

Navigating WyEast Images

The screenshot below shows the main page layout for the companion blog. In the left column you will find (1) the blog logo that also functions as a link back to the main page, (2) a mini-logo that links back to the WyEast Blog, (3) running list of previous posts – these can be viewed as individual pages in addition to simply scrolling the main page, and (4) a link to an “about” page that describes the purpose of the blog and its relationship to the larger Mount Hood National Park Campaign.

Layout of the main page on the new WyEast Images blog

Continuing with the above screen shot,(5) is where you can subscribe to the blog You do need to subscribe separately to the new blog if you prefer e-mail notifications, even if you subscribe to this blog. Moving to the main column on the right, new blog posts appear here, beginning with (6) a photo title with the year the photo was taken and date of the actual post (in small font), followed by a brief narrative about the photo, (7) a detailed description of the image for the visually impaired, and (8) a tiny pop-up menu for managing your subscription to the blog, buried in the lower right corner.

Like this blog, there’s a space to comment on the images when they are viewed on individual pages (by clicking on the image title). I do my best to read and respond to comments – they are always appreciated!

I’ve tested the new blog on a large monitor, tablet and smart phone. It works fine in all three cases, but the format gets clunky on a phone screen. Given the point of the blog, that’s okay with me, as phone can’t do the images justice. The new site really is designed for images to be viewed in at least some of their detailed glory. Thus, computer monitors are ideal, but I am very happy with how it loads and looks on an iPad, as well.

I know there are many iPad users that subscribe to this blog, so here’s a tip for the new WyEast Images Blog: double-tap an image to enlarge to full screen and pinch to return to the regular blog page view. It makes for very smooth scrolling.

Is this Escapism or Activism?

Both! After all, that’s one of the virtues of our public lands – as an escape from our everyday – and a call to action to protect them. That’s where the escape provides the clarity and renewed energy for activism. Works for me every time I step on a trail, and hopefully the large photos in the new blog can provide a virtual version of that feeling. It’s also true that we’re living in a particularly ugly time in our country, so the idea of simply providing an escape for a few minutes to distract with the sublime is a big motivation for me.

My hope is to capture the extraordinary beauty of WyEast Country in a way that is both an outlet from today’s often grim headlines, while inspiring that sense of ownership of the long-term legacy of Mount Hood and the Gorge that is central to caring for these places. Accordingly, photos will range from iconic, world-class destinations to the lesser-known gems and secrets that are often most at risk. The opening narrative for each photo will help tell that story.

Where to find the new blog?

If you’ve read this far, you’ve probably guessed – the new WyEast Images Blog can be found at:

I’ve already posted a few images as part of getting the kinks out, and I hope to add an image every week or so – more, if I’m able to. We’ll see how it goes!

Thanks for reading, and as always, thanks for caring about WyEast Country!

________________

Tom Kloster | January 2026