The prolific 2021 Beargrass bloom at Owl Point

When I posted Part 1 of this article last month, the theme was about the redemptive, restorative power of time spent in the outdoors. At the time, I wasn’t alone in dreading the November elections, and the prospect of a renewed attack on public lands protections (and democracy, itself).

Flash forward one month, and the election landscape has radically changed in ways nobody could have predicted. I suddenly find myself with renewed hope and optimism that the next four years might bring more federal action on the climate crisis and protection of our public lands. Words like hope, optimism and bipartisanship have even found their way back into the national debate.

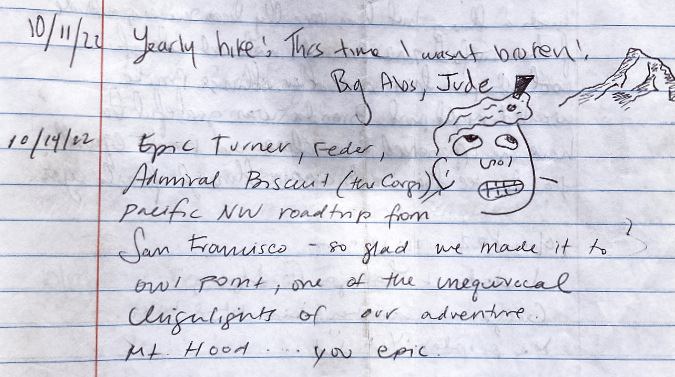

Our antiquated Electoral College system will ensure this election continues to be political nail-biter, yet it was through this lens of renewed optimism that I read through more comments in the Owl Point Register for this sequel. Part 2 of this article draws from the hundreds of messages left in the log between 2017 and 2023, and I chose a select few that further underscore the title of this two-part series.

Read on… with hope!

_______________

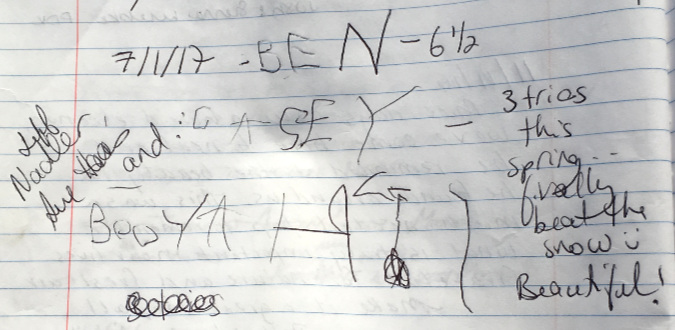

With the country suddenly talking about our shared future, again, what better way to begin Part 2 than with this wonderful message from a determined young family that tried – and succeeded – after three attempts to make it to Owl Point in the summer of 2017:

I so love seeing families on this trail. Here’s another family message from the same month in 2017, in this case with kids old enough to be Swifties:

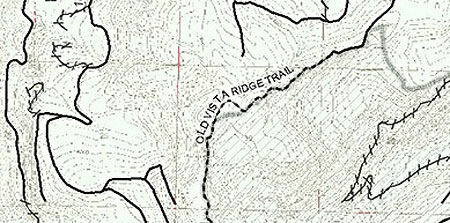

In the Oregon Hikers Field Guide the Old Vista Ridge trail is described as “family friendly” because It’s just long enough to give kids a workout (and hopefully they will sleep all the way home) and sense of accomplishment at reaching their goal at Owl Point. Along the way, there are interesting things that appeal uniquely to kids: short side trails to secret viewpoints, mysterious talus caves, lots of boulders to climb, the “elephant trunk tree” near Blind Luck Meadow and a string of kid-friendly geocaches.

The Owl Point Register serves as one more feature for kids to explore, often writing the entry on behalf of their family, or at least giving their parents an assist. The summit box also has some local history and a guide to Mount Hood’s features for older kids and parents to ponder (more about that toward the end of the article).

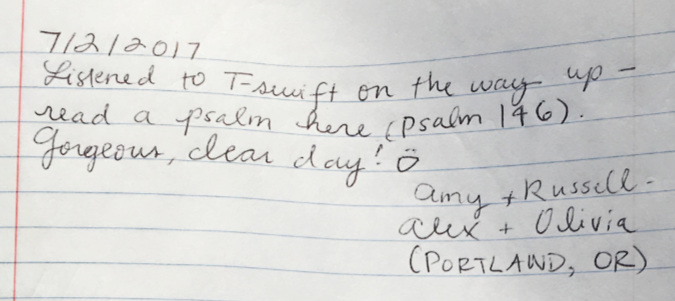

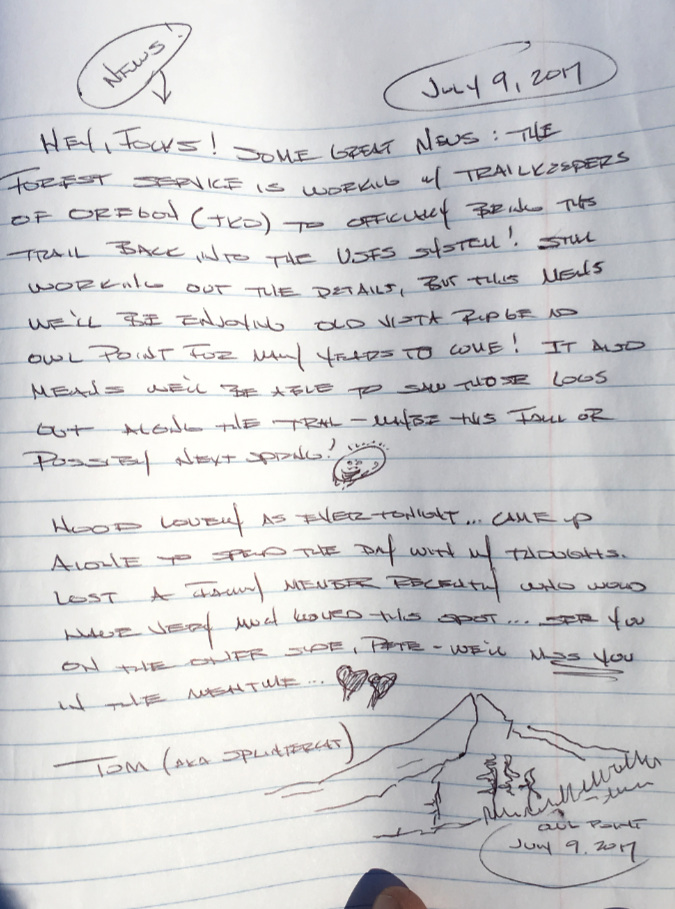

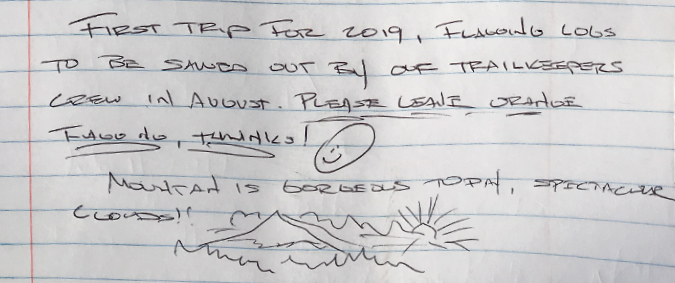

There were a series of important milestones in the Old Vista Ridge trail saga that began in 2017, and led to this old trail formally being recognized by the Forest Service, once again. I previewed what was to come in this message I wrote in early July of that year on my annual scouting trip:

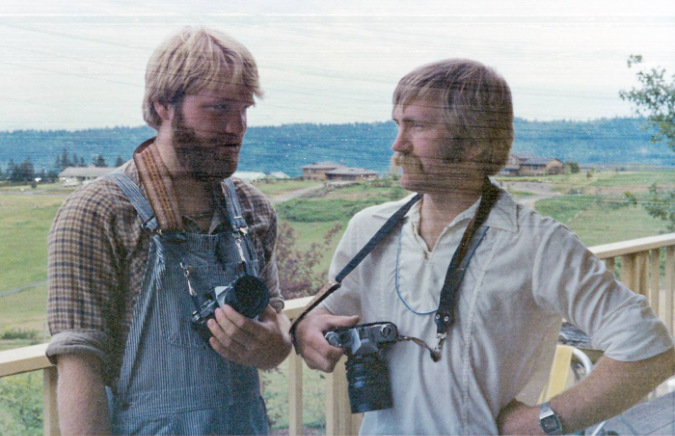

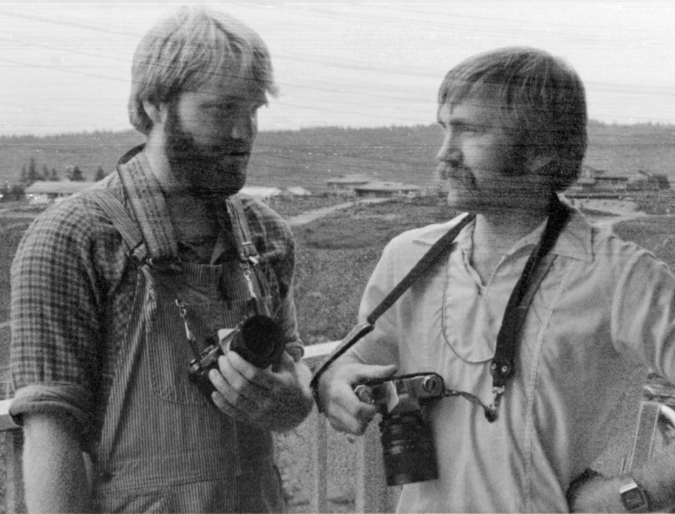

The second paragraph in the above entry refers to my oldest brother, Pete, who died unexpectedly and tragically of suicide that July, at just 66 years old. He died just two days before I wrote this message. Pete was a hero to me in every way, and I still think of him most days – but especially when I’m out on the trail.

I’d forgotten spending that day up on the Old Vista Ridge trail, so soon after his death, until I re-read this message. It makes sense. Owl Point continues to be one of my go-to places when I need to sort out life and regain perspective. As I said in that message in 2017, Pete would have loved it up there, and I only wish I had somehow made that happen when he was alive.

The 20-year-old me and my late brother Pete (right) talking cameras in 1982. Pete got me hooked on photography, music from folk to classical and so much more that defines me today. I can’t blame him for those overalls, however! Such was my wardrobe during my college years. I still have that camera that I’m holding – Olympus OM-1, my first real camera. Pete helped me pick it out. It still works as if it were brand new, and taking a roll of film with it now is like having Pete back, if only for the moment.

Two weeks after that early July scouting trip in 2017, I was joined by Forest Service (USFS) staff from the Hood River District and Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) executive director Steve Kruger for an official walk-through of the trail. The goal was to assess its restored condition and finalize an agreement with the USFS for TKO to adopt and maintain the trail in perpetuity in exchange for it being formally recognized by agency, once again. The USFS team included Claire Fernandez, then the Hood River District recreation manager, and two forest resource specialists, Mike and Ken (below)

Mike, Steve, Claire and Ken at Owl Point on July 26, 2017

Our first stop that day was at the unofficial trailhead, marked by these hand-made signs. The first order of business was to figure out where official USFS trail signs should be located to replace these user-made signs. It turned out that Claire had done some heavy lifting with a few of her USFS colleagues by smoothing over some bad feelings over these unsanctioned signs and advocating for the trail to be formally reopened. I’m convinced that without Claire’s efforts behind the scenes, the official status of the Old Vista Ridge Trail would still be in limbo.

The old user-made signs posted at the Old Vista Ridge trailhead in July 2017

When we reached Owl Point, I held my breath as Claire immediately spotted the register box, then opened it and began reading through some of the messages in the log. I watched out of the corner of my eye from fifteen feet away, pretending to take photos. I was certain we would be asked to remove it, along with the hand-made trail signage. In just five years, the box had become an important part of what made Owl Point such a fun hike, and I was dreading a request to remove it.

Instead, she carefully packed the log back into the register box after reading entries for a few minutes, then closed the lid and didn’t say a word about it to me. I’ve never asked her, but I suspect as a person who has devoted her professional life to outdoor recreation, she appreciated the dozens of joyful, often quite personal notes that people had been moved to write in the log while at the view from Owl Point.

The Owl Point Register box in July 2017

The Forest Service walk-through hike that day finally sent the formal paperwork into motion, and TKO officially adopted the Old Vista Ridge trail later that year. As you will see later in this article, the timing couldn’t have been better, as future events would have made it nearly impossible for volunteers to unofficially keep the trail open.

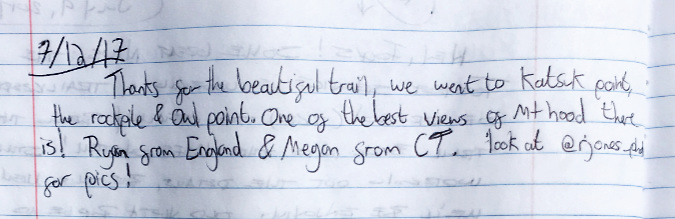

This entry from 2017 jumped out to me for the fact that a pair of long-distance visitors (England and Connecticut) made their way to Katsuk Point, an off-trail, somewhat challenging trek that few hikers attempt:

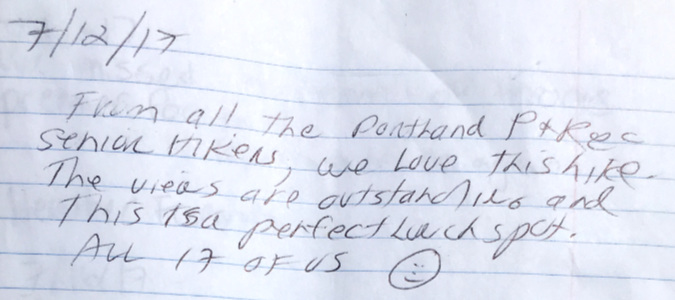

Here’s yet another message from the Portland Parks & Recreation Senior Hikers group. By 2017, they had become annual visitors, with a group of 17 along for this hike:

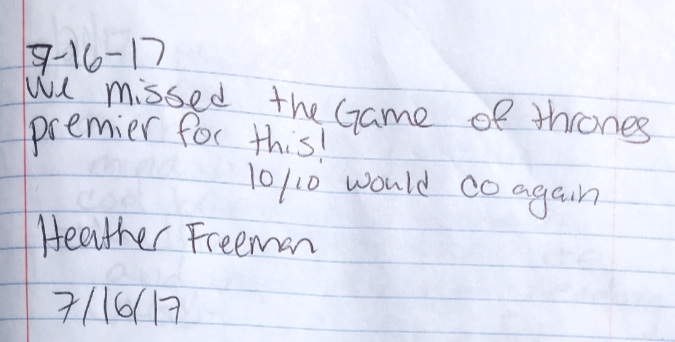

Here’s a message I’ve included as a cultural date stamp, as even the Owl Point Register wasn’t immune from a Game of Thrones reference in 2017 — though I was pleased to see that Owl Point won out over the premier episode!

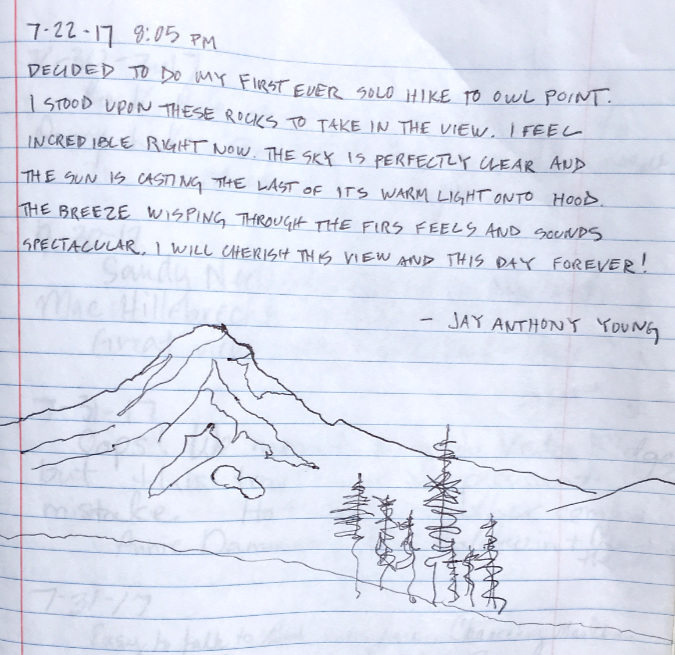

I love the following message from a first-time solo hiker. Noting the date, it is surely must have been one that Claire read when she opened the log four days later? Perhaps it was this wonderful, heartfelt entry that saved the Owl Point Register?

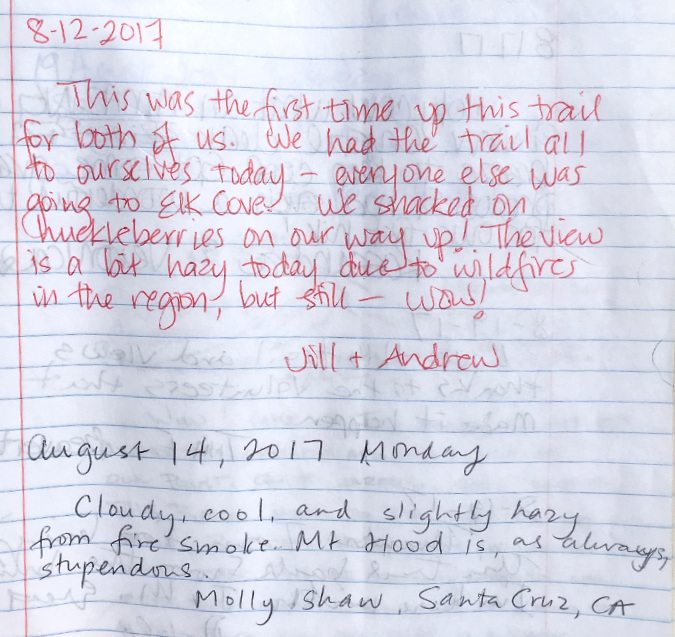

August messages in the log book commonly mention the two things that seem to arrive every summer, these days: huckleberries and wildfire smoke:

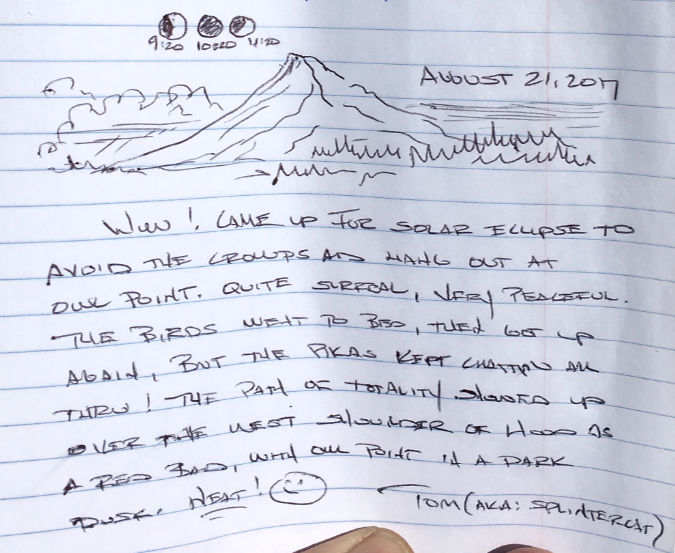

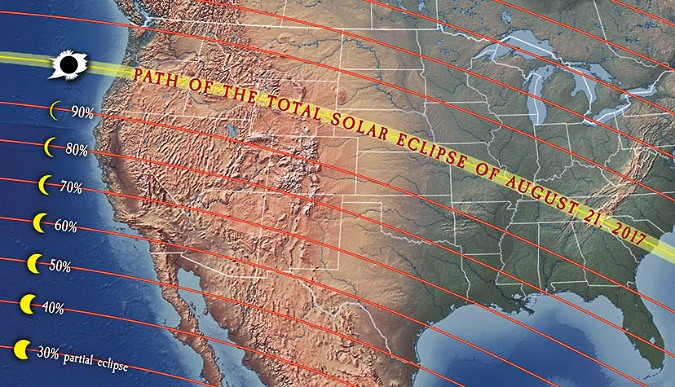

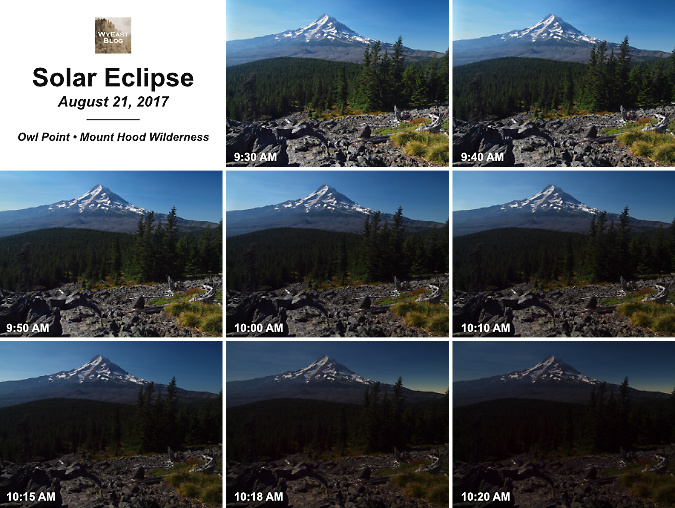

The smoke had cleared a week later when I posted this message (below) in the log on August 21, 2017. The event? The solar eclipse that had turned Oregon into crazytown that year. While Owl Point was just outside the path of totality, I was looking for solitude that day, and decided to experience something short of totality from the Old Vista Ridge Trail, away from the predicted traffic jams. As it turned out, I was the only person there that day!

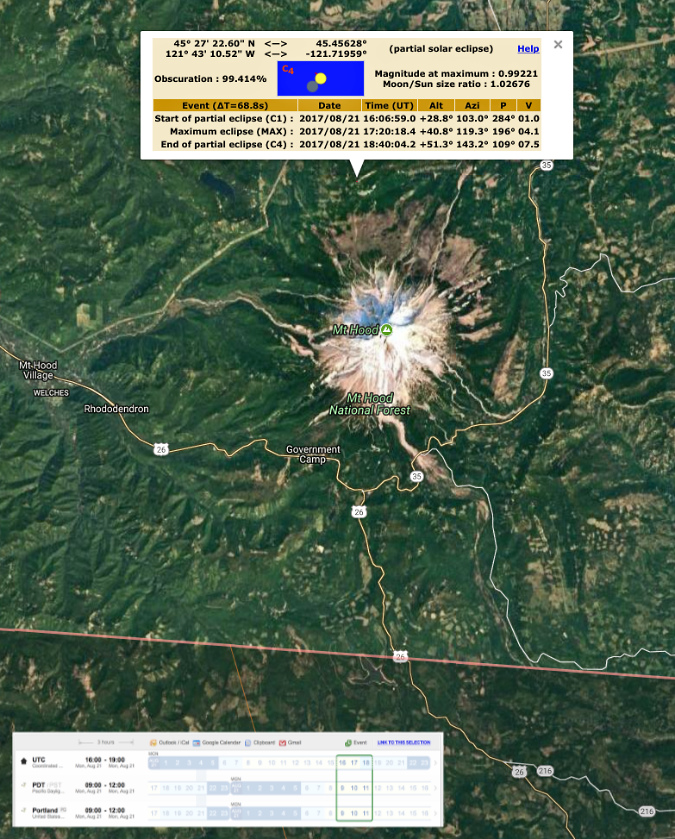

Why, I even included highly scientific sketches of the eclipse phases in my log message! I had, in fact, mapped out the path in detail using some of the tools (below) that were available for eclipse-watchers.

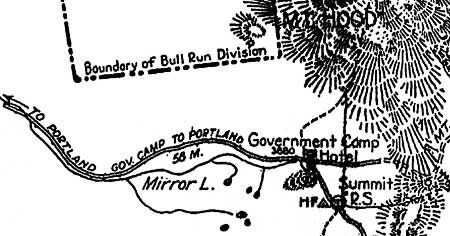

Totality path of the August 2017 solar eclipse

Detailed delineation of the totality zone beginning just south of Mount Hood

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the eclipse, but I wanted to capture both a timed sequence of images and some informal shots. Add in an iPhone, I was busy documenting the slow-motion changes unfolding in the sky.

My camera kit for the day: two DSLRs with wide and telephoto options. Not pictured: two tripods… a heavy load that day!

I arrived at Owl Point a few minutes past 9 AM to find a clear, bright sky. A typical summer day on the Old Vista Ridge trail:

The view from Owl Point in the hour prior to the eclipse

Here’s my camera setup as the eclipse began to unfold. This was taken with my iPhone, and picked up a weird yellowish glare that was filtered out of the images captured on my two larger cameras:

Dual cameras ready to go as the eclipse begins

Assembling a series of images from the camera on the left, this sequence (below) spans the eclipse from beginning to totality. In final two images, the bright band along the west shoulder of the mountain is actually daylight from beyond the path of totality – an unexpected and otherworldly effect.

[click here for a large view of this sequence]

This iPhone panorama was taken as totality approached, and gives a better sense of how strange it was to be looking south, past the path of totality, to the daylight beyond. It might look like a cloud band, but it’s really a thin strip of night passing overhead:

Panorama of the eclipse as it approached totality

I’d created a schedule with 10-minute intervals between timed images, so I also took advantage of the healthy huckleberry crop at Owl Point that day…

One-half water bottle is enough for a huckleberry cobbler…!

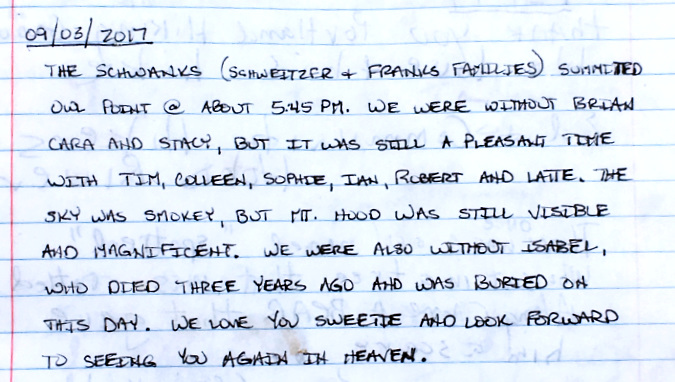

This message from September 2017 (below) is a first in the log – a portmanteau! The Schweitzer + Franks families = the Schwanks! I’m going to guess that Latte was a canine member of the party, and I especially liked the unexpected last part of this entry. So many people are inspired to reflect on lost friends and family while at Owl Point.

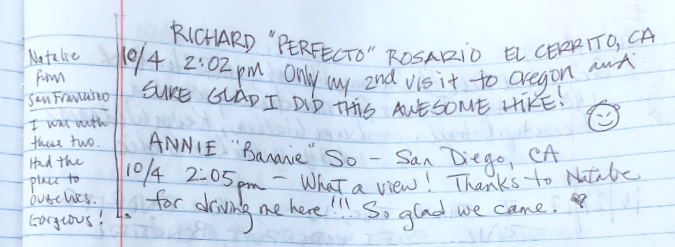

More long-distance visitors from California came to Owl Point to close out the 2017 hiking season:

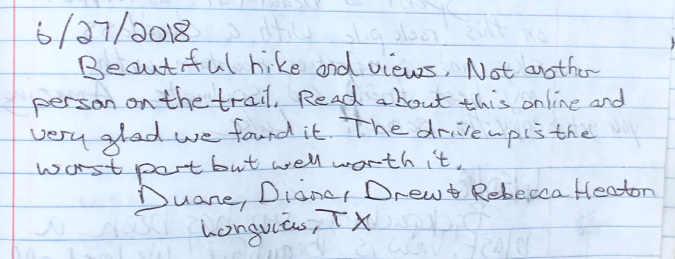

…and these out-of-towners from Texas opened the 2018 season:

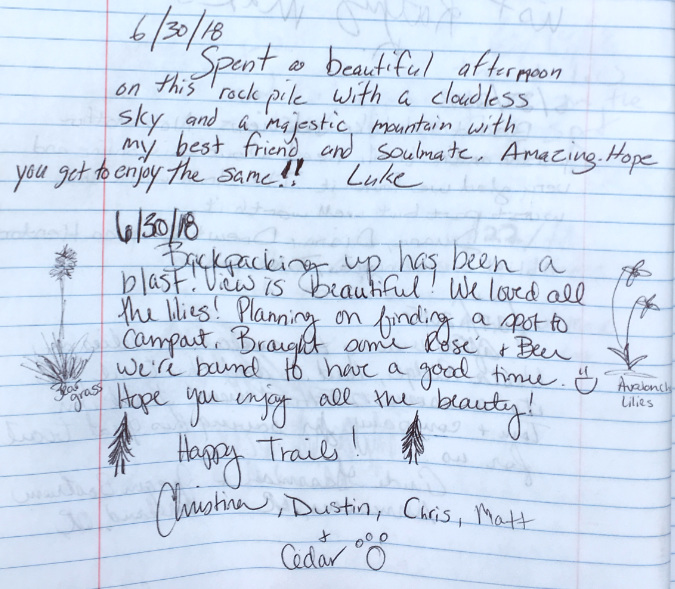

More early visitors in 2018, with the second group spending the night at Owl Point and adding botanical sketches:

While there are a few posts in the Owl Point Log that mention overnight stays, they’re not common. I suspect that’s mainly because there’s no water source up there, and thus the group above would have had to carry water in (including for Cedar) to augment the wine and beer!

Here’s a post from a couple of trail friends that I run into periodically who were up at Owl Point in 2018 as part of the Cascade Pika Watch effort:

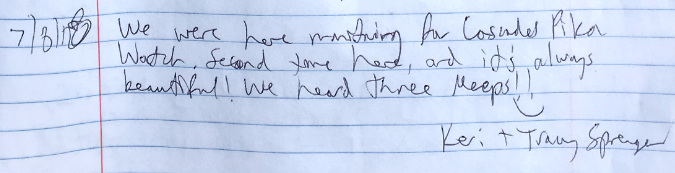

Here’s a notable, if understated, post from that same day in early July, 2018, when the Old Vista Ridge trail was formally re-dedicated as part of TKO’s 10th Anniversary:

In fact, this event had originally been scheduled for September 2017, but the raging Eagle Creek Fire had closed public access to much of the area north of Mount Hood as the fire raced through the Hatfield Wilderness backcountry in the Columbia River Gorge.

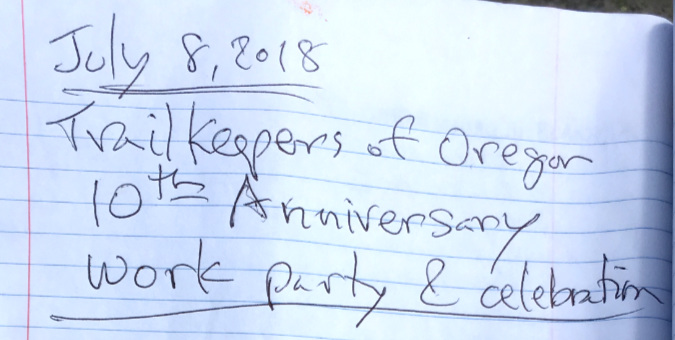

The rescheduled event in 2018 kicked off with a typical trailhead orientation for volunteers, with TKO’s Steve Kruger presiding (in yellow hard hat):

TKO 10th Anniversary trailhead talk at the Old Vista Ridge grand re-opening in July 2018

On this special day, TKO volunteers would be installing official USFS signage along the trail as part of the re-dedication, in addition to the annual tasks of clearing logs and brush.

New trail signs and posts in the USFS pickup in July 2018

These trail signs were installed by TKO volunteers in July 2018 and have survived six winters and counting. Volunteers also lugged six 8-foot 4×4” posts up the trail, each buried 18” in rocky soil – a real workout!

TKO Executive Director Steve Kruger and Hood River District Ranger Janeen Tervo re-dedicating the Old Vista Ridge trail on July 8, 2018. Cutting the ribbon involved a handsaw, loppers and trail flagging, of course. Old and new trailhead signs are leaning against the base of the tree

TKO grand re-opening celebration at Owl Point on July 8, 2018 – the first of our annual TKO anniversary events there

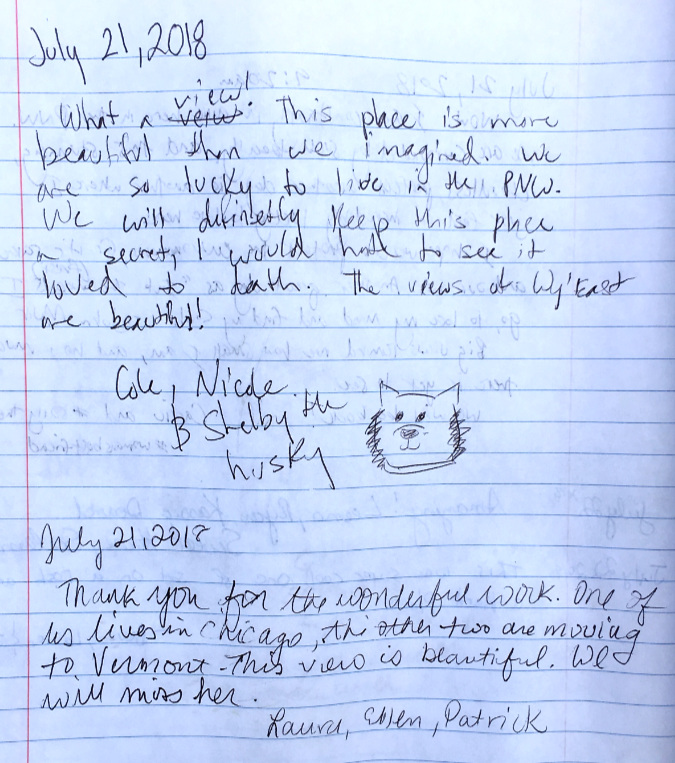

Two groups visiting Owl Point on the same day in late July 2018 shared the sentiment that so many of us can relate to – that we’re so very lucky to live here! My condolences to the folks who made the second entry, too. Vermont is lovely, but not as lovely as the Pacific Northwest (I may have just triggered a few Vermonters):

Another out-of-owner in 2018, this time from Connecticut…

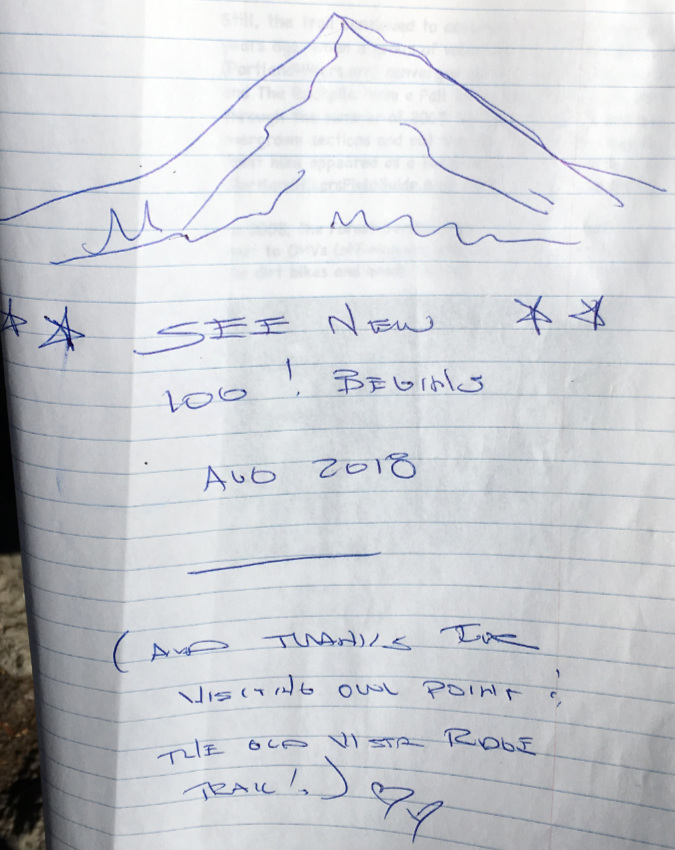

By August 2018, the original Owl Point Log had completely filled, and I placed a blank, new edition. For the next year or so, I also left the original log in place for folks to read, with this message:

Closing out the original Owl Point Log after six years…

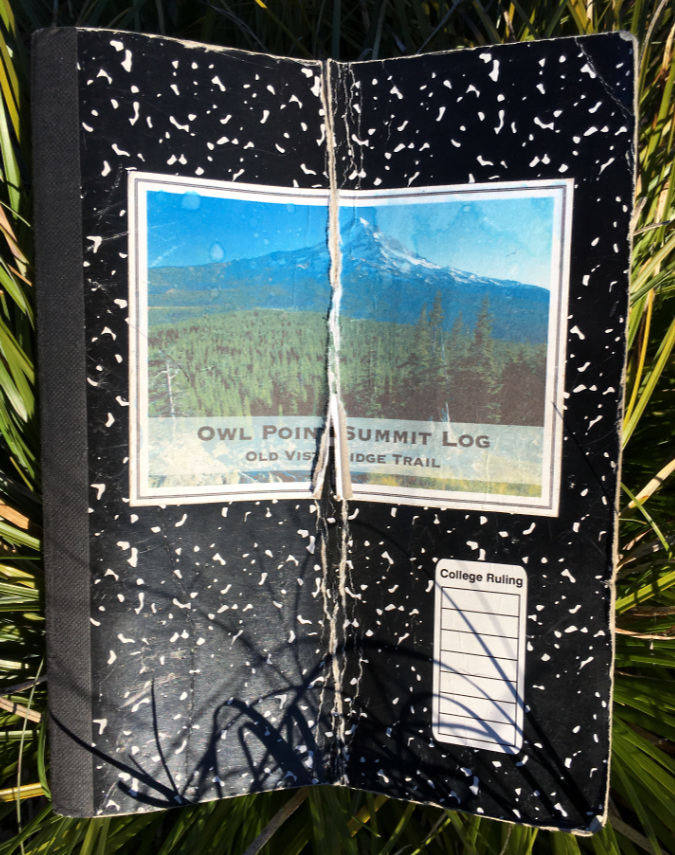

The cover of the original Owl Point Log after six years up on the mountain

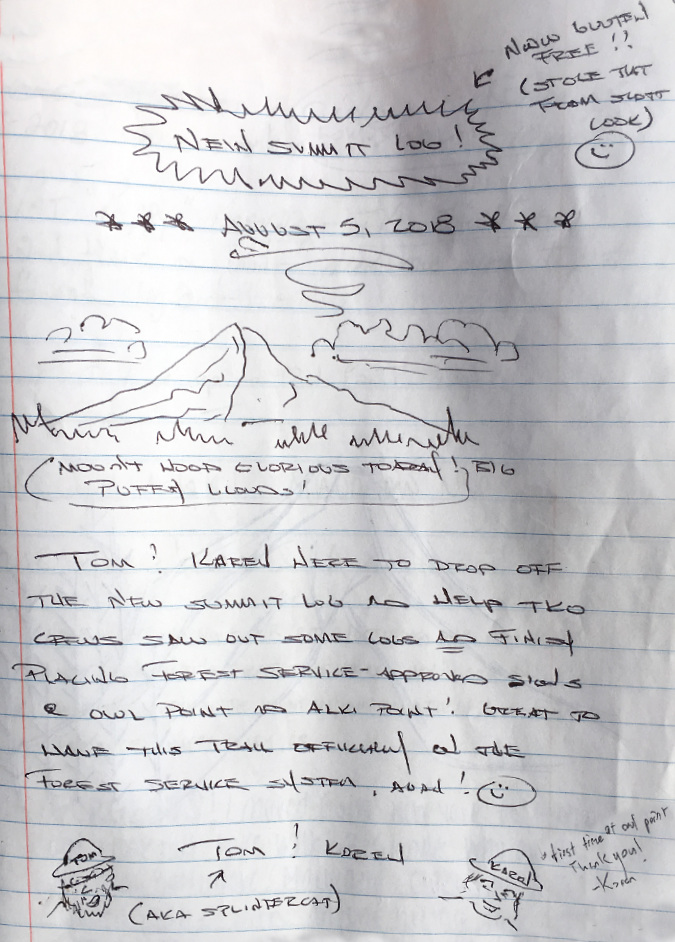

The new Owl Point Log (Volume 2) begins with this message:

I placed the new log as part of yet another TKO trip to the Old Vista Ridge trail on August 5, 2018. Most of the volunteers that day were focused on clearing the last few logs on the trail, but I worked with TKO intern Karen to finish installing the last of the trail signs at Owl Point (below) and Alki Point.

The author and TKO intern Karen installing the (then) brand new Owl Point spur trail sign in August 2018

More out-of-towners in 2018, this time from Maryland visiting a recently transplanted New Yorker:

…and another annual visit in 2018 from the Portland Parks & Recreation Senior Hikers group – 25 hikers on this outing!

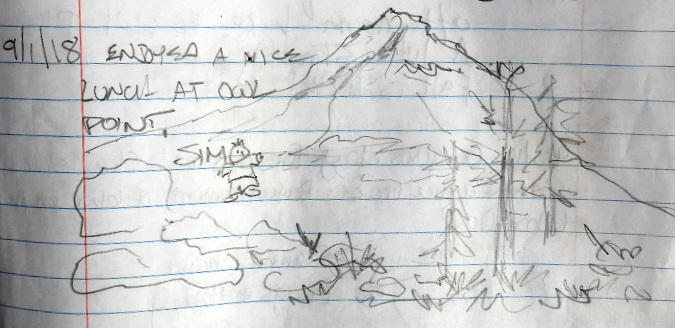

Hiker Jim (below) was apparently so elated with the view from Owl Point in September 2018 that he was suspended in mid-air above the rocks (or so I interpret his sketch):

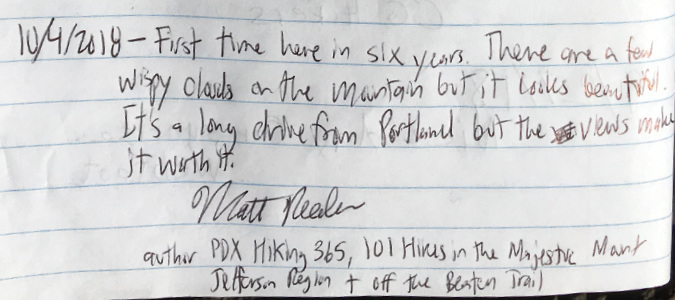

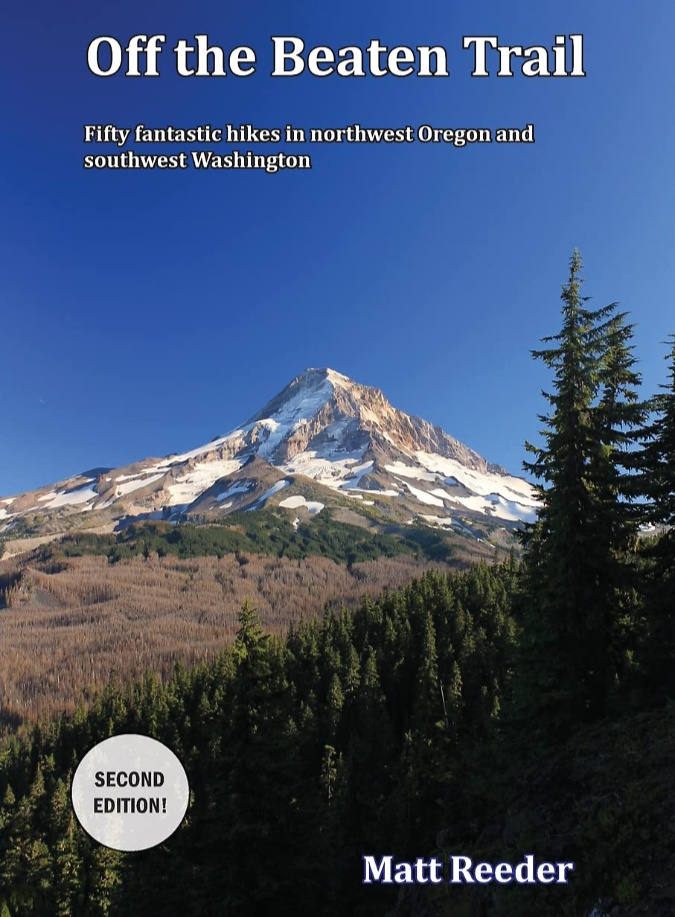

Guide book author Matt Reeder (below) is a longtime friend of the Old Vista Ridge trail, having not only included it in his “Off the Beaten Trail” guide, but also placing a photo from the trail on the cover!

Matt Reader featured a view from the Old Vista Ridge Trail on his “Off the Beaten Trail” guide

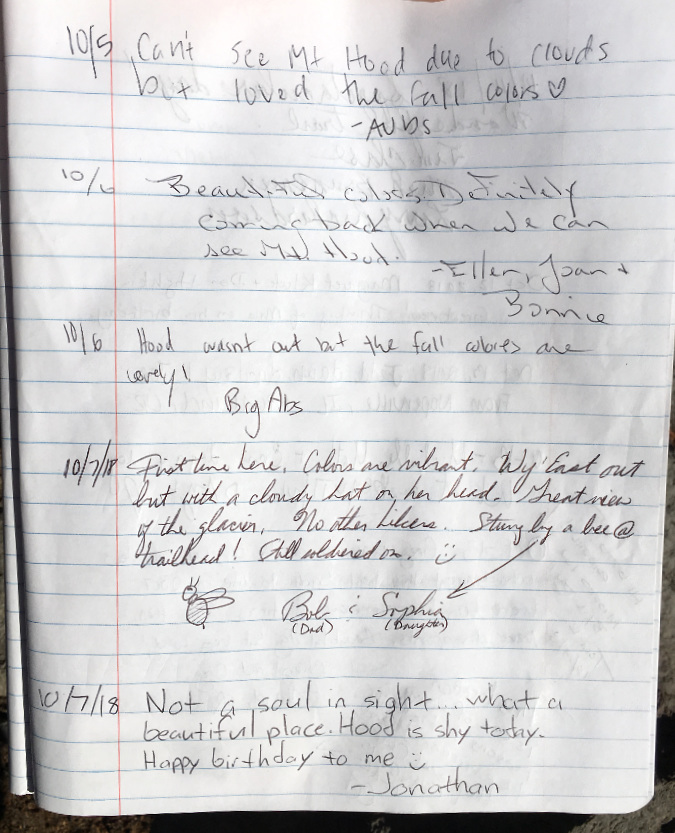

This series of visitors in early October, 2018 shared a common fate: Mount Hood lost in the clouds:

You might wonder why people would pick a viewpoint trail on a cloudy day, but it’s not that simple with Owl Point, especially early and late in the hiking season. Vista Ridge and Owl Point lie precisely on the Cascade divide, a mile-high crest where moist marine air coming off the Pacific often condenses into a low cloud cap, even as Mount Hood rises above into blue skies.

Here’s what it looks like at Owl Point when this happens – this is the view west, into the fog that is seemingly a stationary cloud:

Cloud cap engulfing Owl Point on a fall day

Yet, looking east toward the Hood River Valley you can see the cloud isn’t stationary, at all – and, in fact, is dissipating right above you, with blue skies to the east:

Looking toward the Hood River Valley and Surveyor’s Ridge from under a cloud cap at Owl Point

Here’s what that effect looks like from up on the Timberline Trail – a “cloud waterfall” of marine air condensing into a rolling fog bank as it pushes from the west (left) over Vista Ridge and Owl Point, then cascading and evaporating into the dry air mass to the east (right in this photo) side of the divide:

Cloud cap forming a “cloud waterfall” at Owl Point

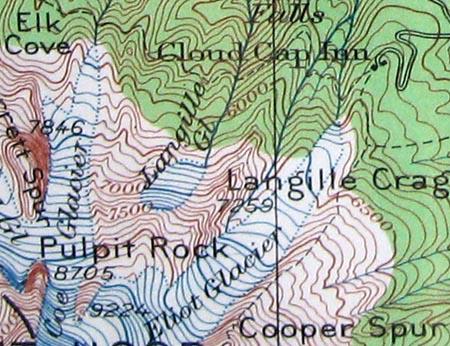

This effect can be very local, or become widespread when a weak Pacific front pushes in, as shown in this view from above Elk Cove, looking down on the Cascade divide and Owl Point:

Widespread “cloud waterfalls” along the Cascade crest – the view looking north from Mount Hood toward Mount St. Helens

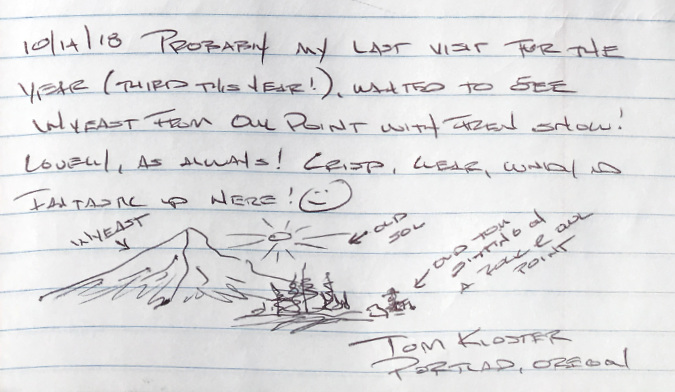

Even on the clearest spring and fall days, cloud banks can form over Vista Ridge and Owl Point without notice. The clouds those October 2018 hikers encountered had cleared by the time I visited later that month, with an added bonus: they had dusted the mountain with an early coat of fresh snow – a magical time of year on the mountain:

The dusting of snow on Mount Hood described in my October 2018 log entry

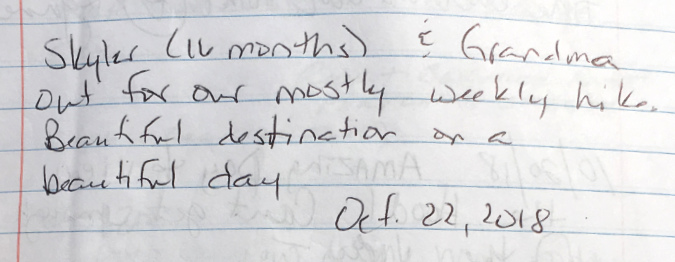

Here’s a message from a dedicated grandma – with her 16-month toddler – that caught my eye:

This post from 2018 mentions another guidebook that helped bring folks to the Old Vista Ridge Trail, Paul Gerald’s popular “60 Hikes within 60 minutes of Portland” guide. A lesser-known fact is that Paul served on the TKO board for several years, including a stint as TKO board president. Thank you, Paul!

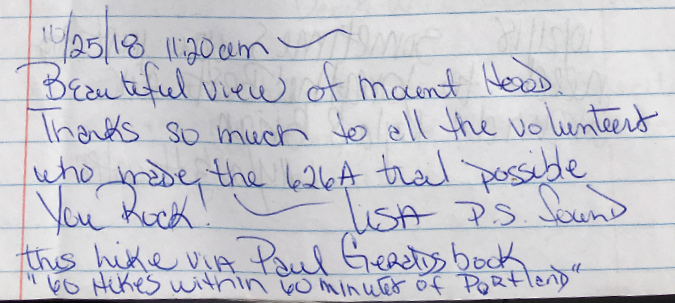

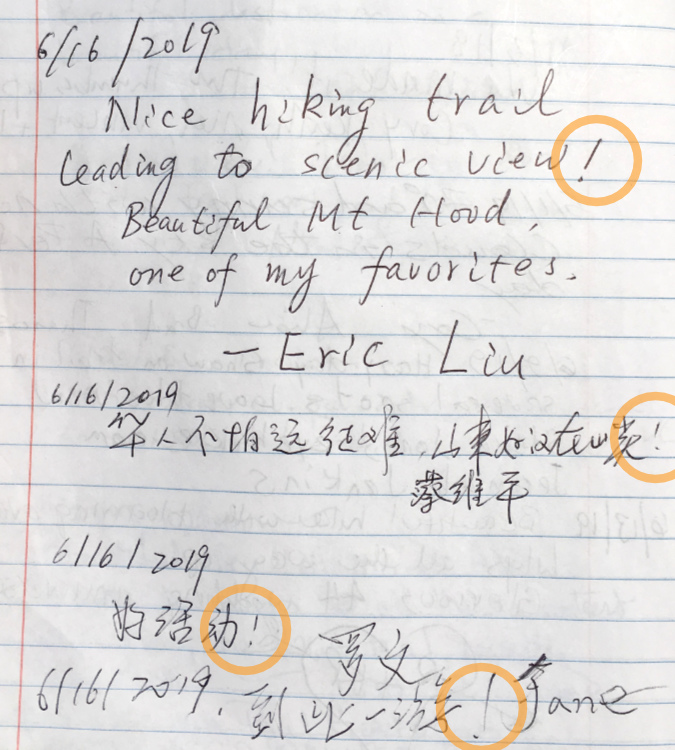

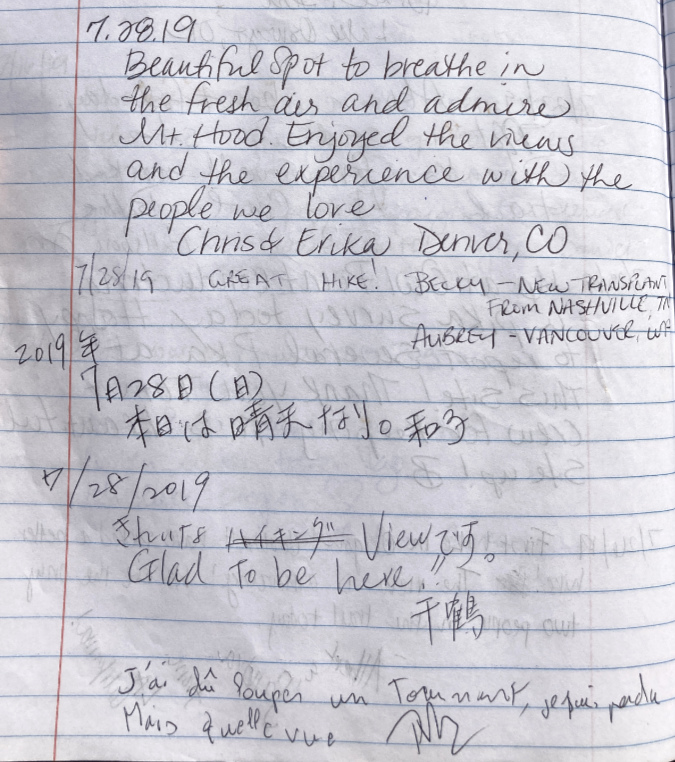

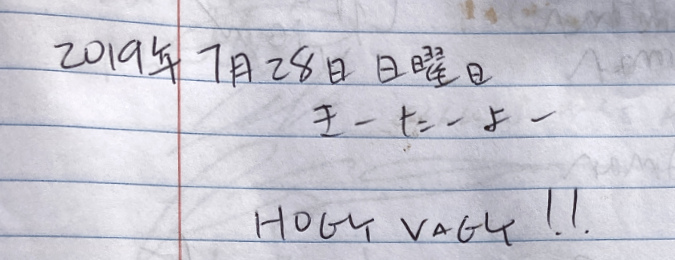

Kicking off the 2019 hiking season, this is perhaps the most international series of messages to date in the Owl Point Log:

I’ve circled the exclamation marks – while I can’t read the least three messages, they all seem to have been impressed with the view from Owl Point!

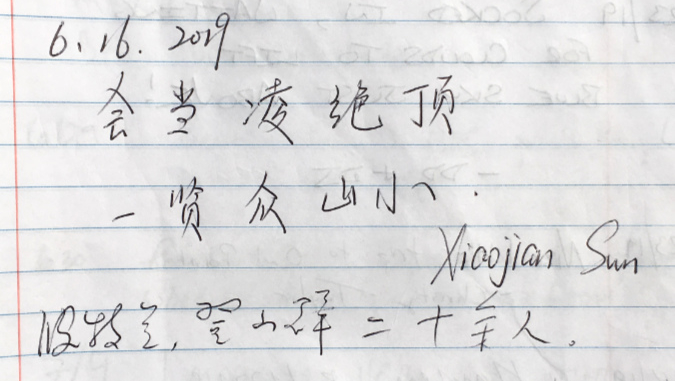

Here’s one more from that group of international visitors in 2019 (and if you are a reader of this blog and can translate any of these messages, please add as a comment):

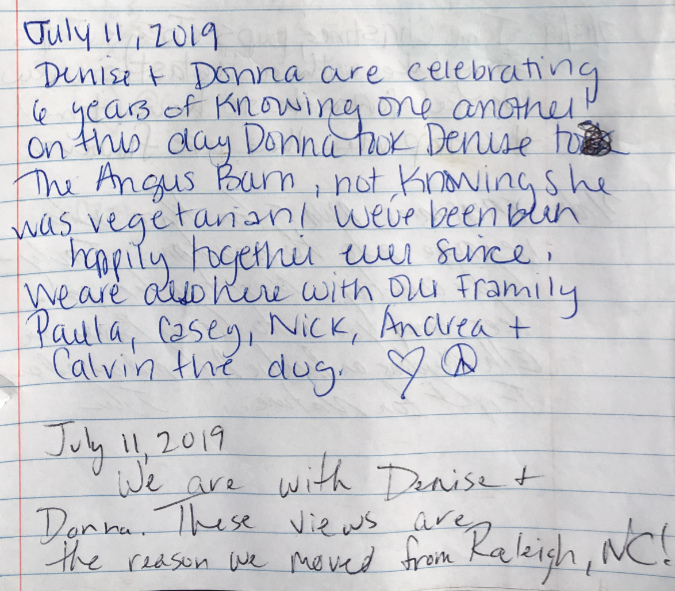

An “opposites attract” milestone message in July 2019, plus more out-of-towners from North Carolina:

…and yet another milestone message. There have been a few marriage proposals and baby announcements, but this is the first adoption announcement to appear in the Owl Point Log. I especially loved that a subsequent visitor added a congratulations:

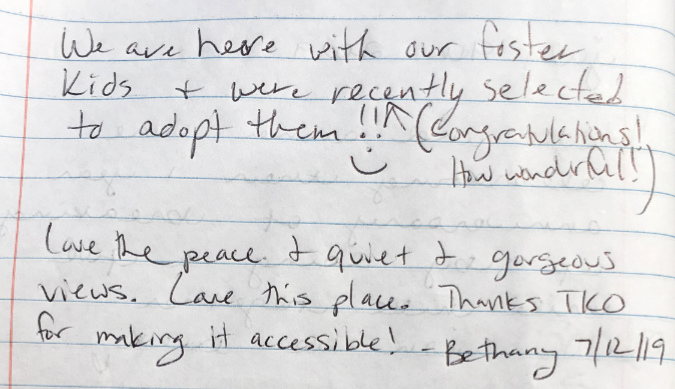

Here’s the first “animal in heat” (!) sticker to appear in the log, along with some very polished cartoons:

Yet another pair of entries from the author, this time on a scouting trip in July 2019 for the annual TKO anniversary event on the Old Vista Ridge Trail:

When I re-read this message for this article, I wondered just how gorgeous those clouds really were? Digging back into my photo archives, it’s true – they were spectacular:

WyEast looking lovely under painterly clouds back in the summer of 2019

…the mountain was pretty nice that day, too!

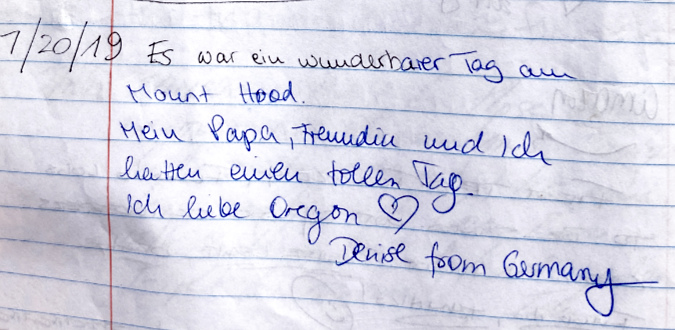

Here’s another long-distance visitor in 2019, this time from Germany:

My rough translation of the above entry: “It was a wonderful day at Mount Hood. My dad and I had a great day. I love Oregon.” German speakers, help me out if you can!

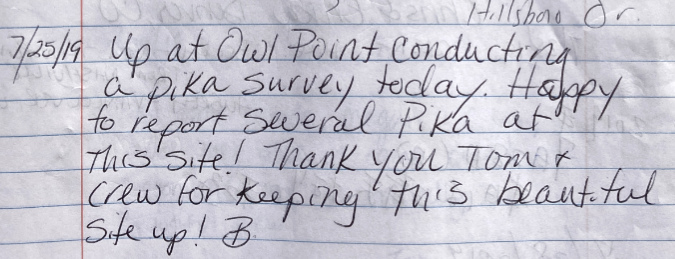

Also from July 2019, another successful Pika survey:

It doesn’t surprise me that Pika thrive here. While their habitat throughout the west is threatened by climate change, much of the talus (their sole habitat) faces southeast and is shaded from late afternoon heat by the Owl Point ridgeline and stands of Noble fir. Hopefully, this will be enough to keep their familiar “meep” calls coming from the rocks here for decades to come.

Here’s a string of recent arrivals (from Nashville) and more long-distance visitors who stopped by on the same day in July, 2019 (if you can help with translation, please add a comment).

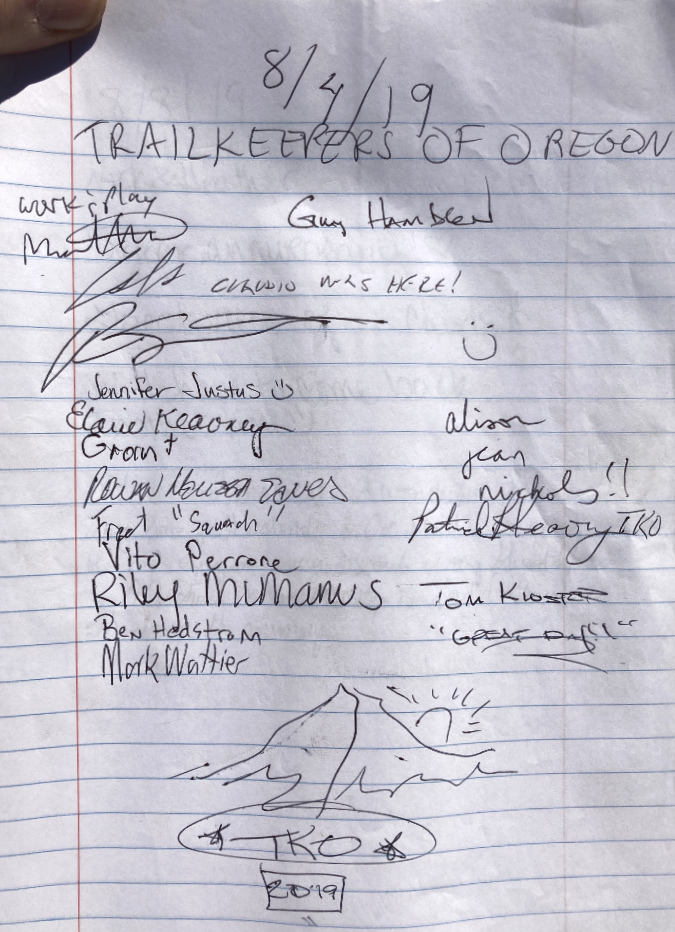

August 2019 brought the second annual TKO celebration to the Old Vista Ridge trail (below) with another large group of volunteers for our annual trail tending. More logs to clear, more huckleberries to brush away from the trail and another fine day up at the mountain!

In that second year of what has since become our annual tradition, we captured the next in a series of group portraits that continue to this day (below). So far, the mountain has been out for every one of our events up at Owl Point. Though that streak surely can’t last forever, it does make for a great photo opportunity:

Team portrait from the annual TKO stewardship event in 2019

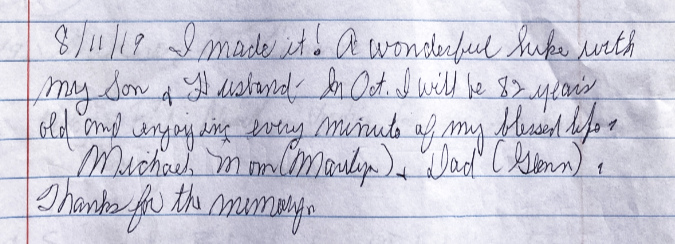

Here are a few more excerpts from 2019 in the Owl Point Log, beginning with this post that is personally inspiring to me, as hiking until I die is one of my life goals!

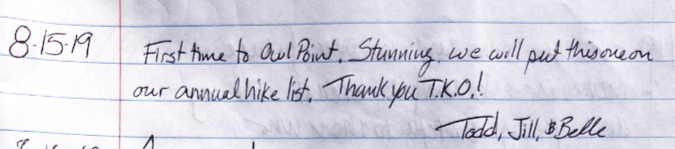

This post from first-timers in 2019 carries a common theme found through the log – that Owl Point is now on their annual hiking list:

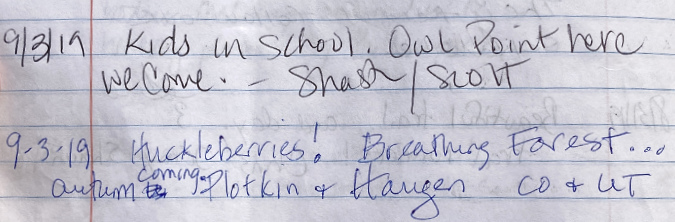

This entry from September, 2019 made me smile – a couple of parents who survived summer break with kids seeking refuge at Owl Point and more out-of-towners (Colorado and Utah) discovering our huckleberries:

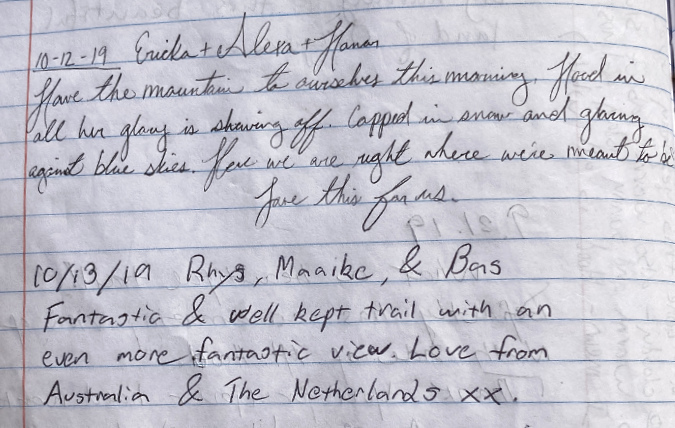

These back-to-back entries from October 2019 provide a nice contrast of “locals right where they’re meant to be” followed by more faraway visitors from Australia and The Netherlands reminding us that we live in a slice of Heaven here in WyEast country:

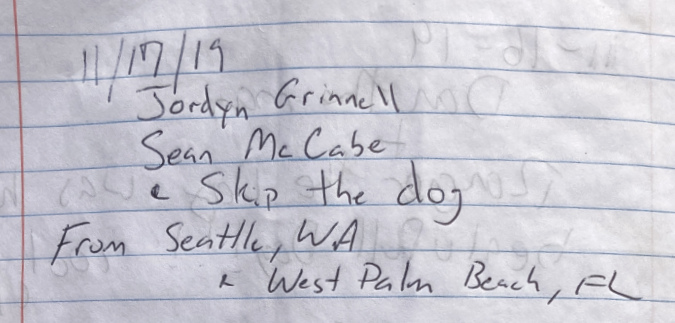

More out-of-towners from Seattle and West Palm Beach to close out the 2019 season, just ahead of the first snowfall that year:

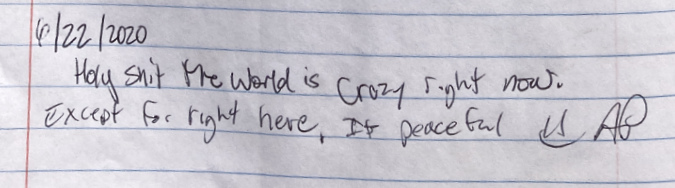

As the snow began to fall that winter, burying the Old Vista Ridge trail under several feet of snow, we couldn’t have imagined that the entire world was about to turn upside down. Even our public lands were closed to entry in those early weeks of the COVID pandemic in the spring of 2020. By June of that year, public lands had reopened, and masked, pandemic-stressed hikers began arriving at Owl Point:

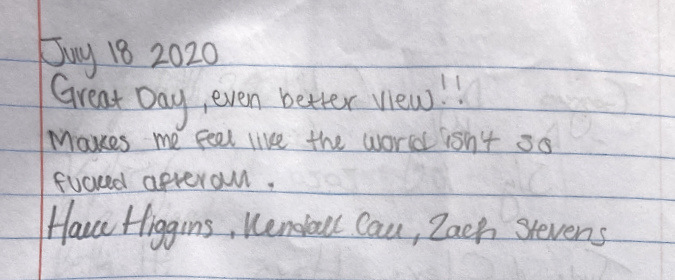

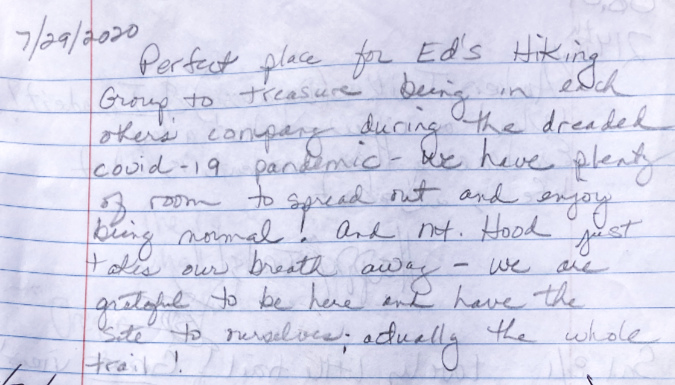

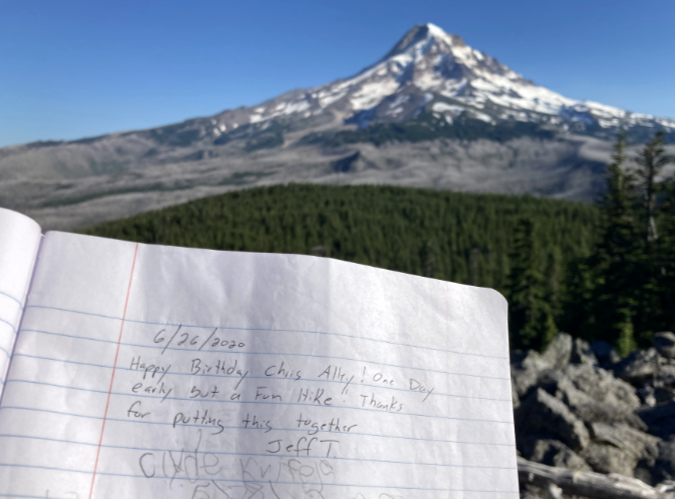

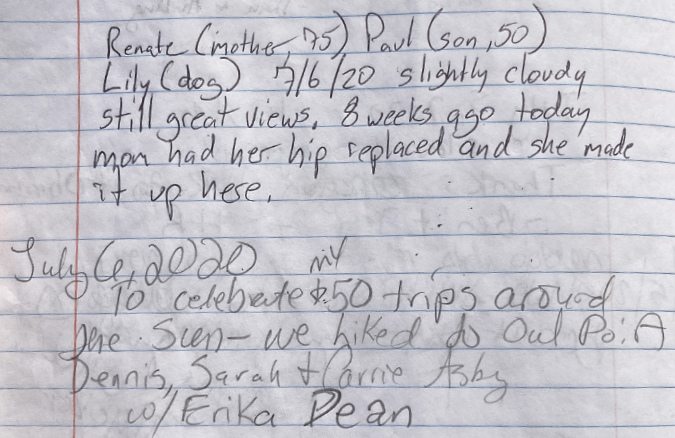

As if charting the five stages of grief, messages in the Owl Point Log in 2020 become more circumspect as the summer season arrived. Pandemic commentary gave way to life milestones and personal reflections as socially-distanced people reconnected with one another on the trail – among the safest places to be during the pandemic.

These friends reunited to celebrate a birthday (Chris is mentioned in Part 1 of this article):

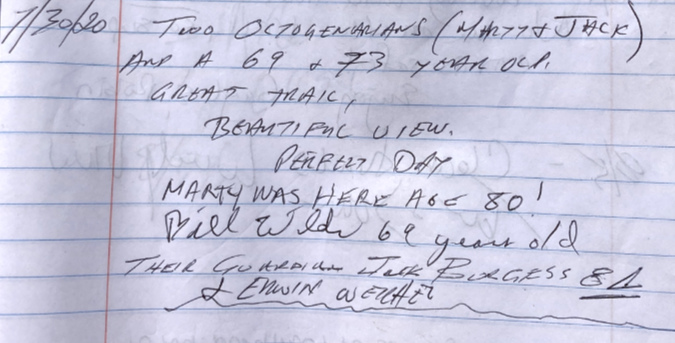

Trails were an especially important refuge for older hikers in 2020, considered the most vulnerable among us to the COVID-19 virus – like these veteran hikers:

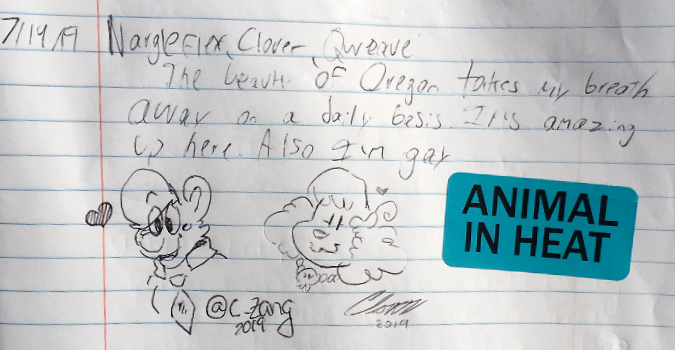

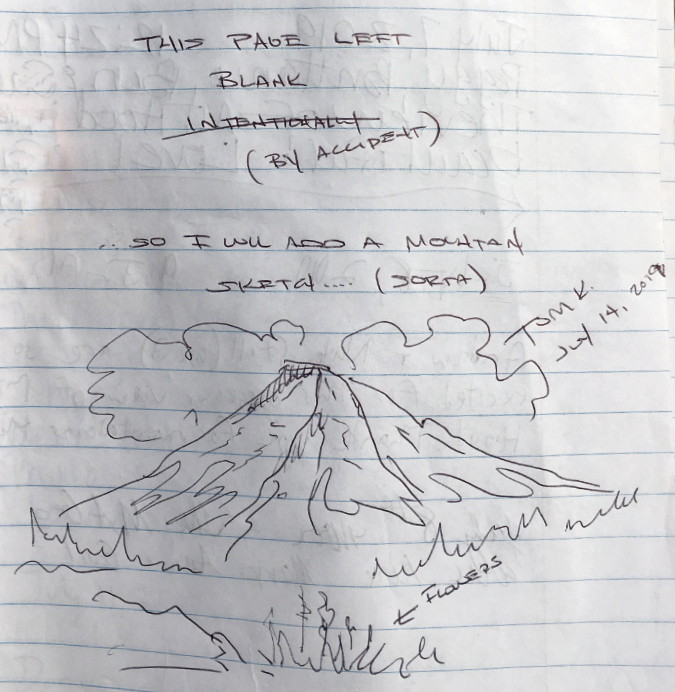

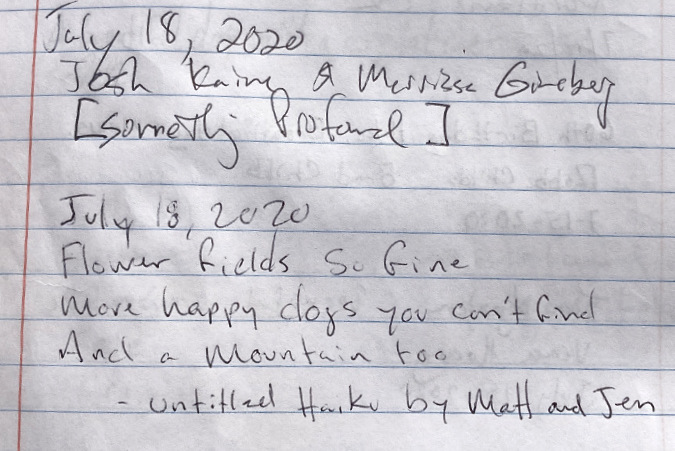

This pair of messages (below) from July 18, 2020 caught my eye. Hikers Matt and Jen filled in the creative blank left by Josh and Marissa on – collaboration!

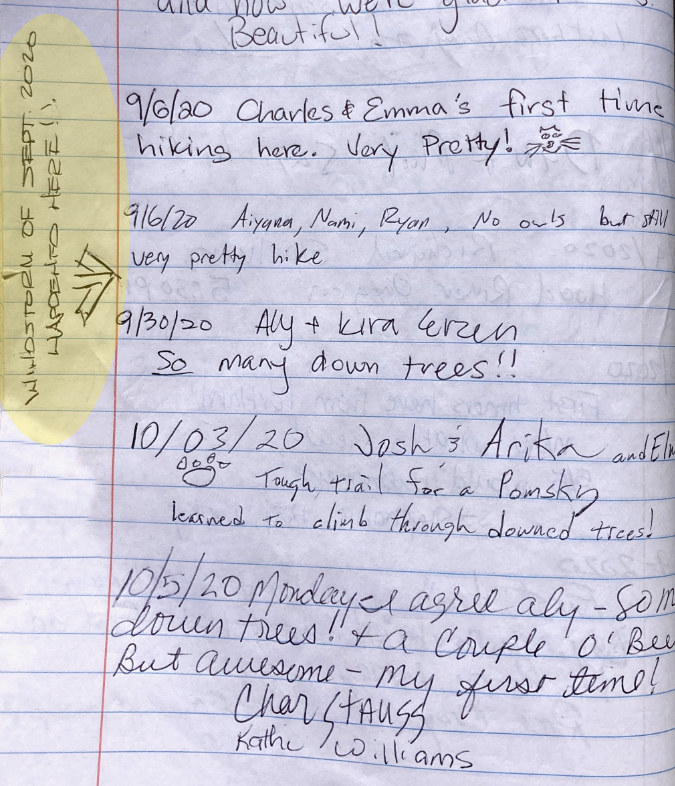

The year 2020 had more unpleasant surprises for Oregon with the Labor Day windstorm and subsequent forests fires that raged up and down the Cascades. Owl Point was not spared from the wind event, and you can spot it in the Owl Point Log comments. I’ve highlighted a comment I wrote in the margins that fall to mark the windstorm:

The mess was as bad as the many comments in the Owl Point Log suggested. Dozens of trees were down, especially along the first mile of the Old Vista Ridge Trail. Here’s what the trail looked like in the spring of 2021, when I made my first trip to survey the damage:

Blowdown from the 2020 Labor Day windstorm burying the Old Vista Ridge Trail

Most startling were the number of very large trees that went down at the Old Vista Ridge trailhead. Yet, somehow the sign TKO volunteers had installed just two years before was (mostly) spared in jumble of debris:

Dented but still standing – the Old Vista Ridge trailhead sign after the 2020 Labor Day windstorm

The author surveying the damage from the 2020 Labor Day windstorm

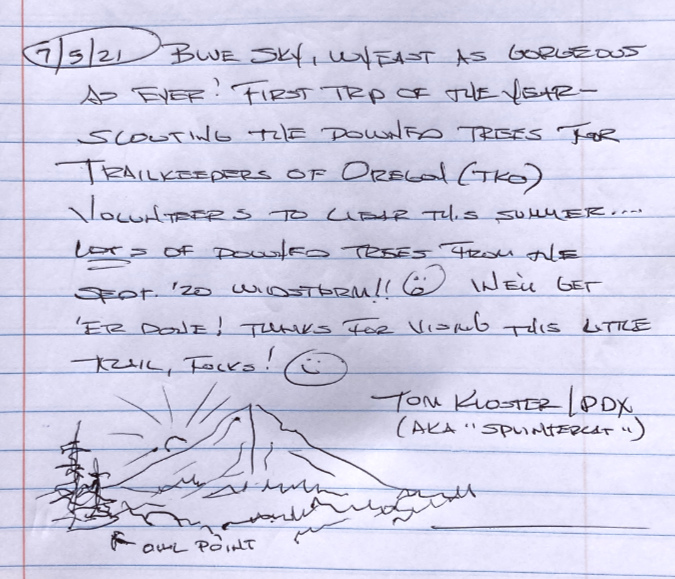

It would still be a few weeks before TKO volunteers were scheduled to clear the mess in the summer of 2021 when I added the following message, so I included a bit of encouragement to hikers who were still pushing their way through debris to reach Owl Point that year:

This was the scene on August 11, 2021 when TKO volunteers descended upon the Old Vista Ridge trail and began the task of clearing dozens of downed trees:

TKO volunteers tackled many piles of fallen trees like this in 2021 (Photo: TKO)

TKO used the event as an opportunity provide crosscut saw training to volunteers, a requirement in wilderness areas where power saws are banned:

TKO volunteers clearing the trail one log at a time with crosscut saws (Photo: TKO)

Newly cleared section of the Old Vista Ridge trail in August 2021 (Photo: TKO)

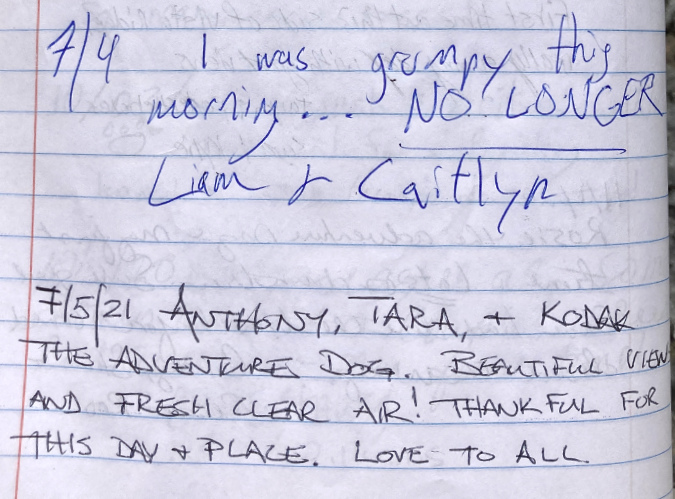

Despite the messy trail conditions that year, you could feel the collective exhale of folks as the pandemic restrictions were gradually lifted. Plenty of thankful messages like these appear in the Owl Point Log:

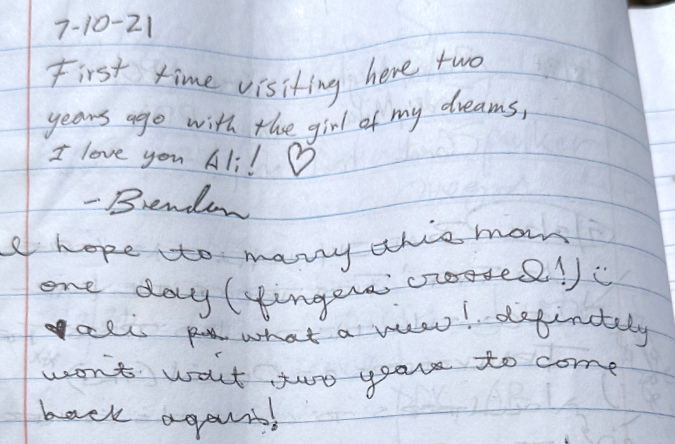

This is a fun post from that summer (below). Ali got the last word in, but do you think Brendon knew what she had written?

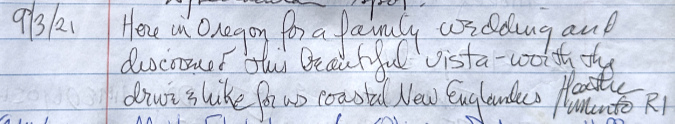

Meanwhile, these Rhode Islanders were in Oregon for a wedding in September 2021:

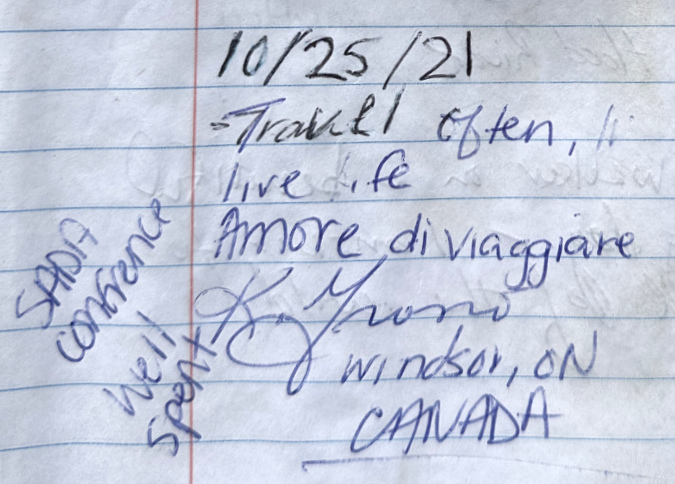

That year brought the first out-of-towners from eastern Canada, too:

Here’s the final from 2021 – an especially philosophical message left very late in the hiking season:

The 2022 hiking season arrived with a very late snowmelt, as noted by these long-distance visitors from the Netherlands:

There were still big snowdrifts in a few spots when I visited a week later with my old friend Ted and his two kids, who were home from college. It was a brisk, breezy and beautiful day to show off the beauty of Owl Point to some first-time visitors:

The author giving Ted and his kids a tour of heaven

Ted’s kids asked for some extra adventure, so I obliged with an off-trail visit to Katsuk Point and one of the more dramatic ceremonial Indian pit located nearby:

Blustery, beautiful day at Katsuk Point

Off-trail Indian Pit near Owl Point

Here’s another thoughtful message (and a toast!) from that summer, posted by out-of-towners from Minnesota and Wisconsin:

…and another Wisconsin group from the week prior – girls trip!

Mount Hood seems to inspire haiku – this entry was added in late August of 2022:

Not surprisingly, this isn’t the first mention of aliens in the Owl Point Log, but it might be the best:

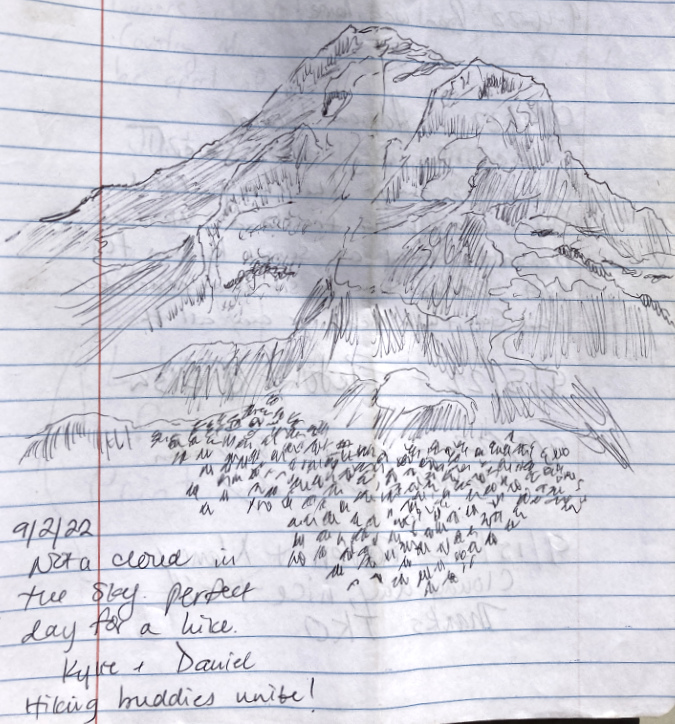

Hiking buddies Kyrie and David left this very detailed sketch of the mountain in September 2022:

More locals returning to Owl Point in October 2022, plus road-trip out-of-towners from the Bay Area admiring our mountain:

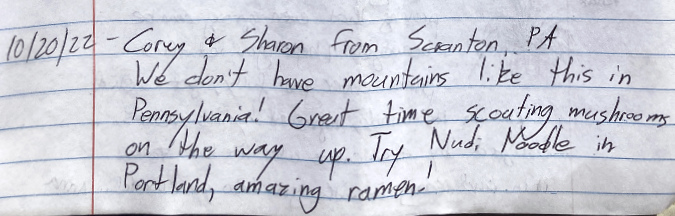

Among the last messages from 2022 is from these Scranton, Pennsylvania out-of-towners, who were also enthused about trendy restaurants in Portland:

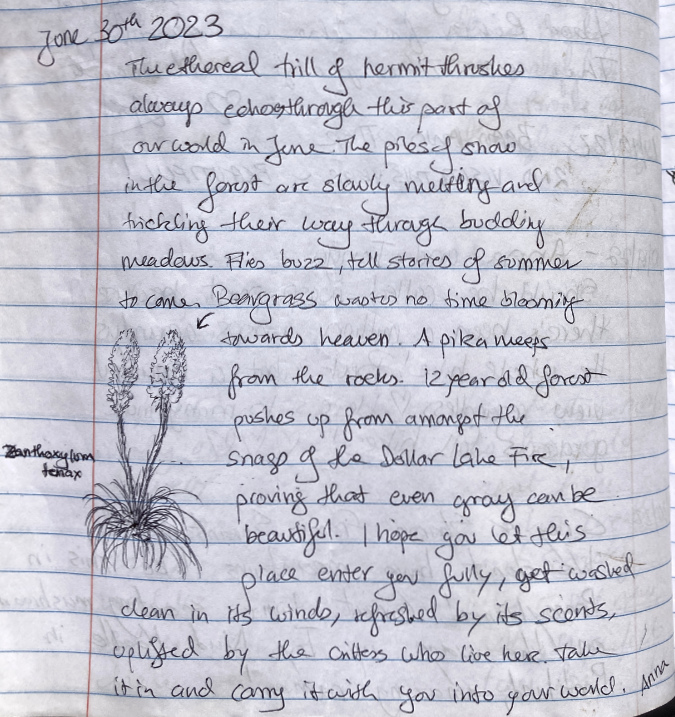

The 2023 season opens with one of the finest entries to date in the Owl Point Log. Hiker Anna gives a literary spin to the natural history of the area, including a nice botanical sketch of Beargrass in bloom (the second in that I’ve included in this article):

Beargrass and Avalanche Lilies are mentioned often in the log by early summer visitors, so to put a face on these wildflowers, here’s a quick primer on these favorites.

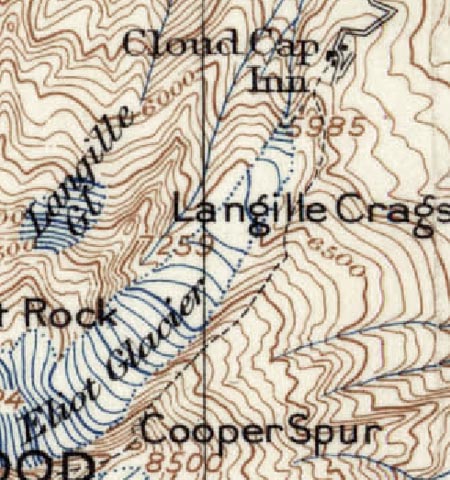

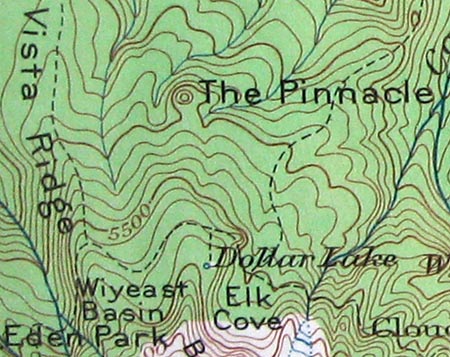

First up, Avalanche Lily. The explosion of these lovely wildflowers in the Dollar Lake Burn area has made the main Vista Ridge Trail a new favorite among photographers, but there are plenty of these lilies growing along the northern sections of the Old Vista Ridge trail. The form carpets of white flowers under the Noble Fir canopy in late June and early July, especially in the section between Blind Luck Meadow and the Owl Point junction.

Avalanche Lilies near Owl Point in early July

Beargrass is also found throughout the hike to Owl Point, but it is most prolific in the area around Blind Luck Meadow and fringing the talus slopes at Owl Point, itself. Beargrass blooms in June and early July on tall spikes that gradually unfold whorls of tiny, individual blossoms from the bottom, up.

This example at Owl Point has just begun to bloom:

Beargrass bloom beginning to unfurl

Here’s an example of Beargrass at Blind Luck Meadow at it peak, with the top of the spire fully open. For photographers, this is the Beargrass bloom stage they are seeking:

Beargrass in full bloom

Beargrass are fickle in their blooming habits. While there’s a widespread myth that these flowers bloom in seven-year cycles, it is true that individual plants rarely bloom in consecutive years. The abundance of blooming Beargrass in a particular area is more a measure of abundant spring rainfall, soil moisture and especially access to sunlight. Owl Point had prolific Beargrass years in 2016 and 2021, while other years had few or no bloom at all.

2016 Beargrass bloom at Owl Point

Another myth is that bears eat Beargrass roots. Also not true, though deer and elk to graze on their foliage, and bears have been known to use their leaves as bedding. Native peoples also used the tough leaves from Beargrass in woven baskets and the fleshy roots for medicinal purposes.

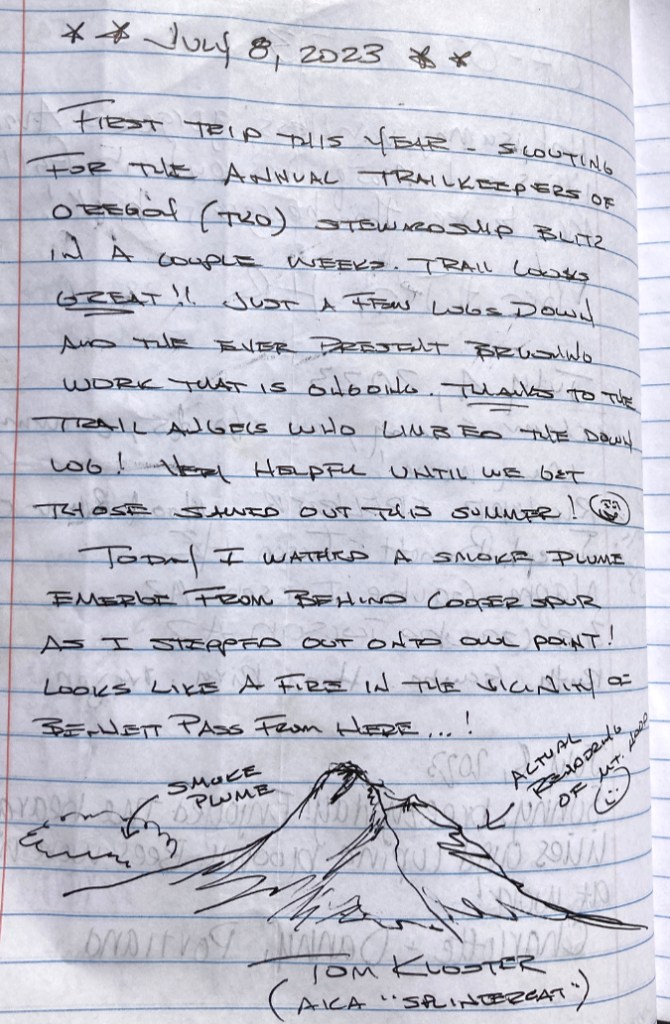

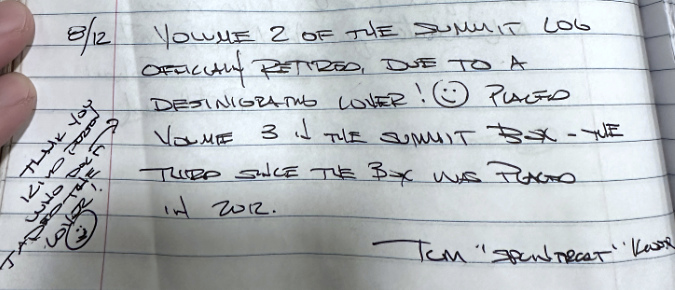

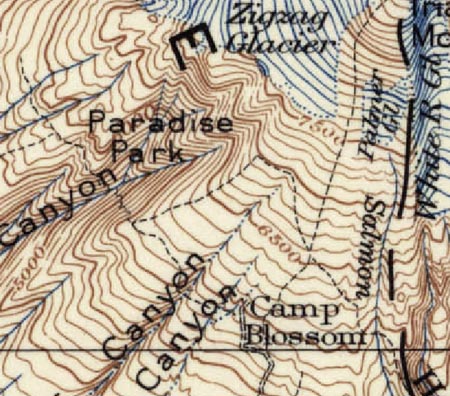

This brings me to the conclusion of the second volume of the Owl Point Log book in, with yet another entry of my own, made while on a TKO scouting trip in July 2023. Notable in this message was the plume of smoke that I watched rising from the east shoulder of the mountain while I was at Owl Point that day. The fire turned out to be further south, along the White River. By the time reached home that night, it had exploded into a substantial fire.

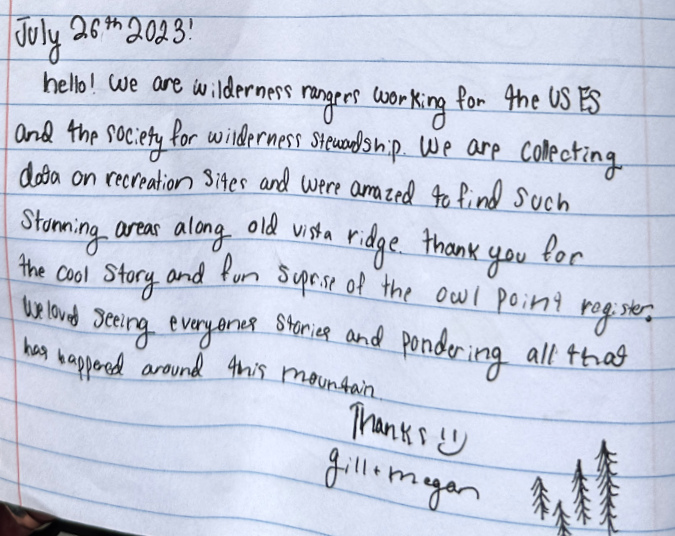

Then, there was this entry from later that month in 2023 (below) by two USFS rangers researching the trail. Once again, I was relieved to read that they appreciated the Owl Point Register box and log book – and the view, of course!

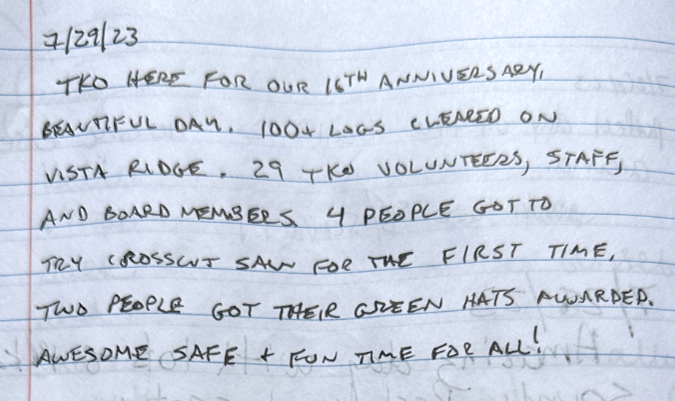

This note (below) marked the most ambitious annual TKO outing to date on the Old Vista Ridge Trail. Not only were there volunteers clearing logs and brush along the Old Vista Ridge trail, a separate group had backpacked to WyEast Basin and spent two days clearing over 100 logs from the main Vista Ridge trail with crosscut saws.

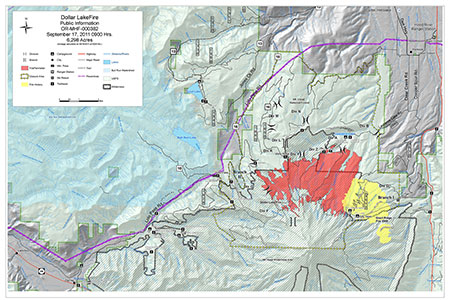

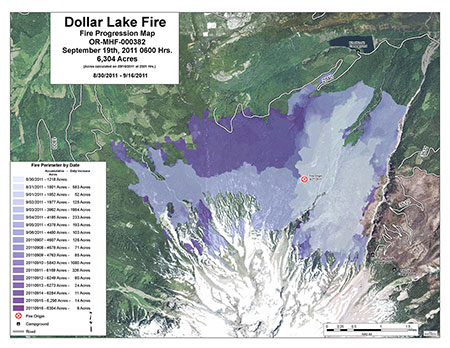

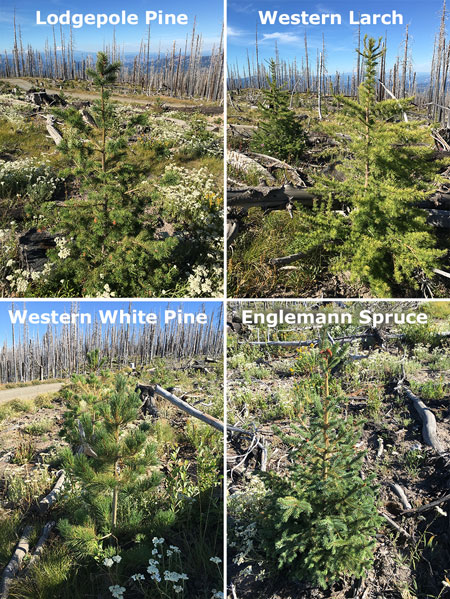

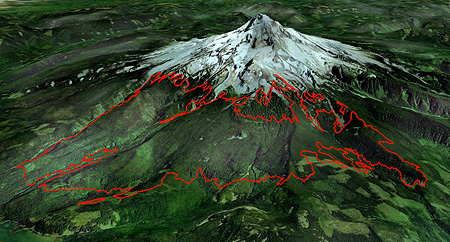

The annual event portrait for 2023 (below) shows both crews meeting up at Owl Point for lunch. On hand were a couple gallons of ice-cold lemonade (hauled two miles in!) and several dozen homemade cookies. The bright yellow sunshades mark the overnight crew that worked the Vista Ridge trail – a very exposed area since the 2011 Dollar Fire swept through.

The dual-crew TKO meetup at Owl Point in 2023

TKO crosscut crews on the main Vista Ridge Trail for an overnight logout in July 2023 (Photo: TKO)

Crosscut crews celebrating 110 logs cleared in two days in 2023

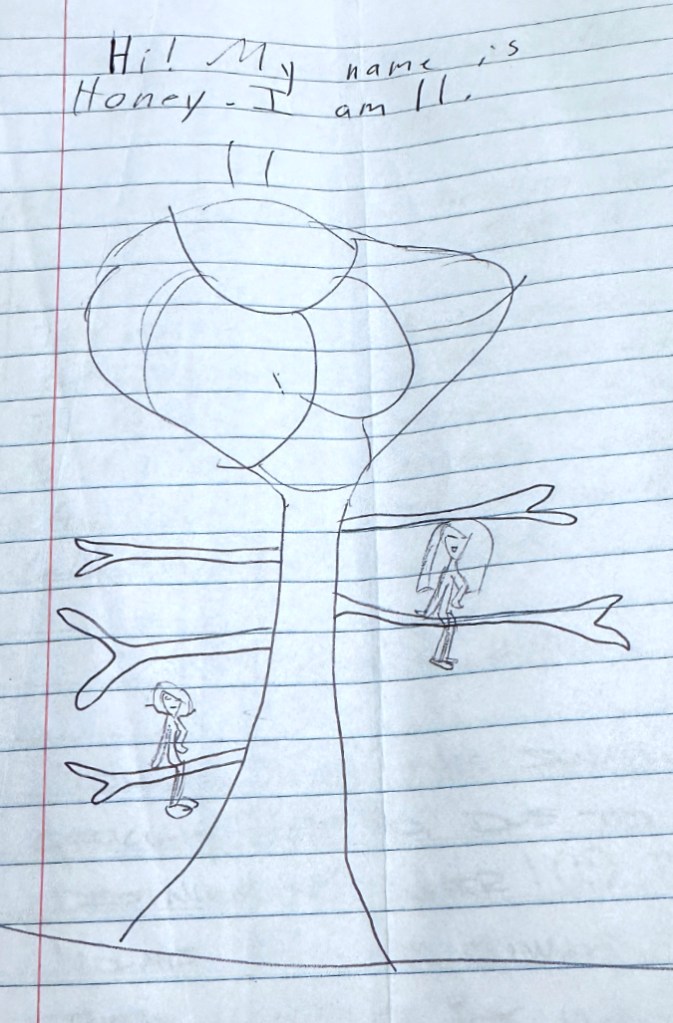

The final (and perfect) entry in Volume 2 of the Owl Point Log is this artful sketch (below) by Honey. I’m going to guess that Honey climbed a tree while at Owl Point?

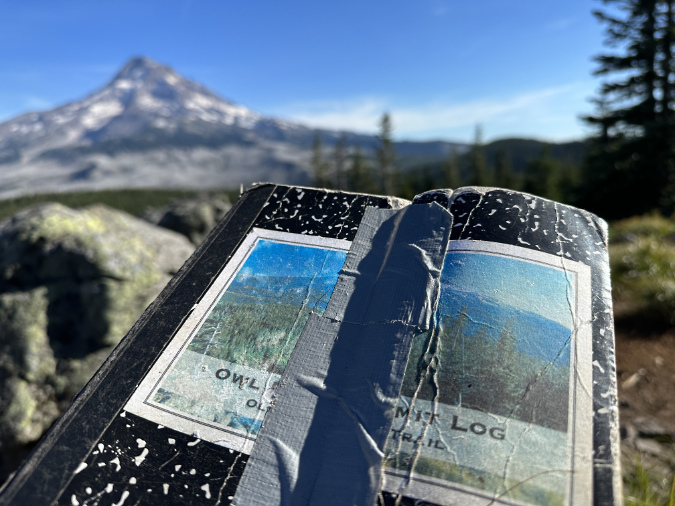

The second volume was close to full by August 2023, but worse, the cover was falling apart. A kind visitor had done some first aid with duct tape, but alas, it was time to retire this one…

The second volume to the Owl Pont Log was well-loved..

And so, I left this note to close out the second volume:

Where are the first two volumes of the Owl Point Log kept? In TKO’s archives – which really means a closet in my home office. When TKO does have an archive, someday, they will move to that more appropriate place.

The archived first and second editions of the Owl Pont Log… safe in my closet

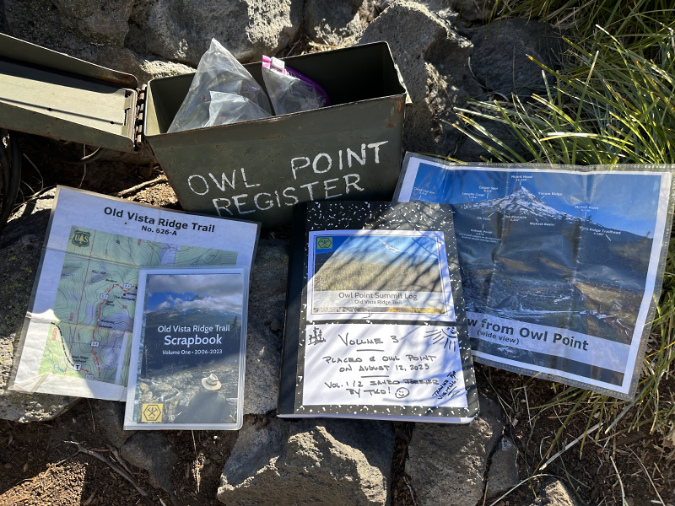

…and so, in August of last year I place the third volume of the Owl Point Log in the summit register, along with a fresh version of the Old Vista Ridge scrapbook, maps and visual guide to Mount Hood’s features (below). Judging by the folds, and comments in the log, these get well-used by hikers wanting to learn a bit more about the area and Mount Hood.

The contents of the Owl Point Register – log, scrapbook, maps and a guide to Mount Hood’s features

And what about the box, itself? So far, it’s doing remarkably well (below), considering the abuse it receives from the elements up on Owl Point. I painted it with army-green Rustoleum back in 2012, and though it’s showing some rust around the edges, It has remained water-tight for twelve years and counting.

Eleven winters and counting at Owl Point

[click here for a large version]

For those who don’t recognize it, the box is an old Army ammo can that I picked up at the venerable (and since closed) Andy and Bax in Portland. At some point, I’ll need to replace the box, as well – and find a new army surplus store!

What’s ahead for the Old Vista Ridge Trail?

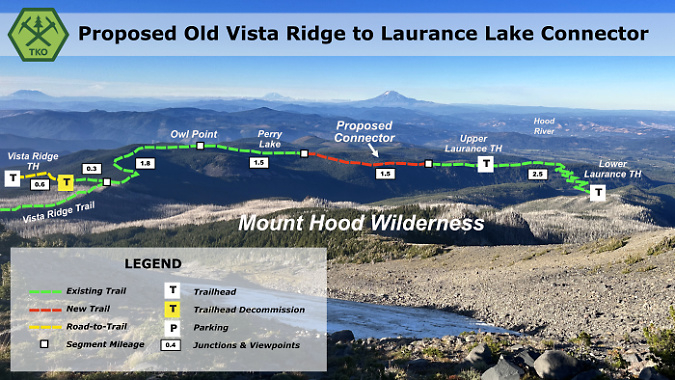

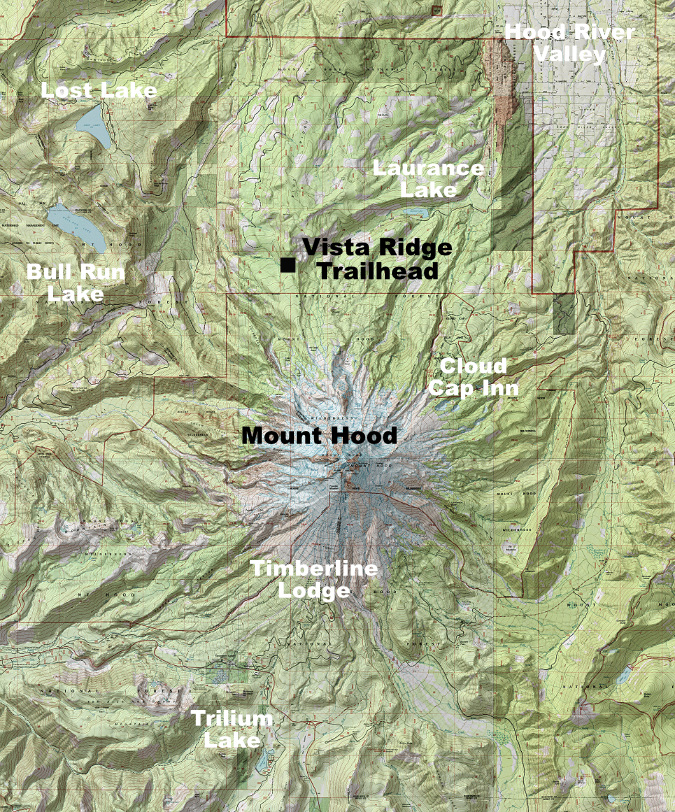

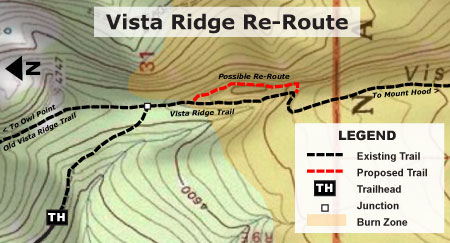

When TKO adopted the Old Vista Ridge Trail – our founding trail – it was part of a broader vision for the area that TKO presented to the Forest Service in 2016. There are lots of proposals in that vision for improving trails and trailhead on the north side of Mount Hood. Among them, the next priority is to provide a route to Owl Point from the east, from the Laurance Lake trailhead.

TKO volunteers clearing a log near Owl Point in July 2024

Currently, TKO’s adopted segment of the Old Vista Ridge trail ends at this sign (below), at Alki Point. From here, the unmaintained trail continues downhill to the site of the old Red Hill Guard Station and tiny Perry Lake (more of a pond).

TKO intern Karen helping plant the “trail not maintained” sign at the end of the adopted segment of the Old Vista Ridge Trail in 2018

TKO’s vision is to construct a roughly one-mile connector from Perry Lake to the upper trailhead of the Laurance Lake trail. This schematic shows the proposed connector, as viewed from high on Mount Hood, looking north:

[click here for a large version]

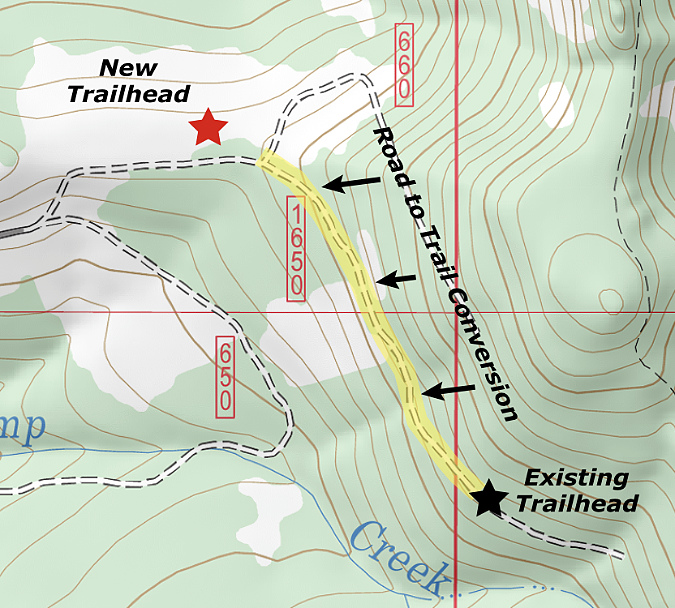

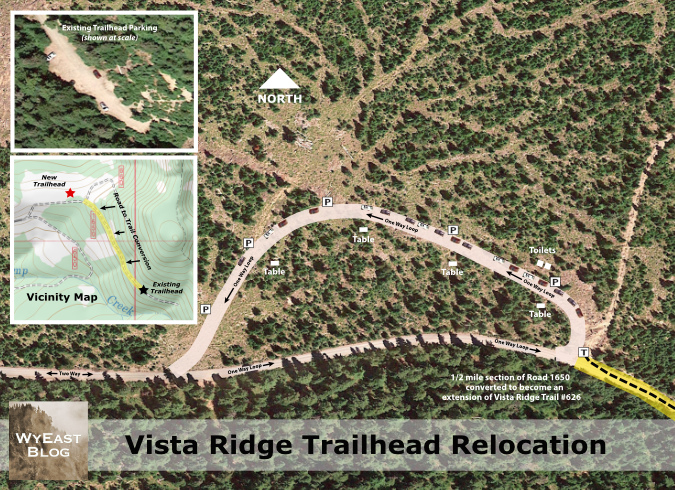

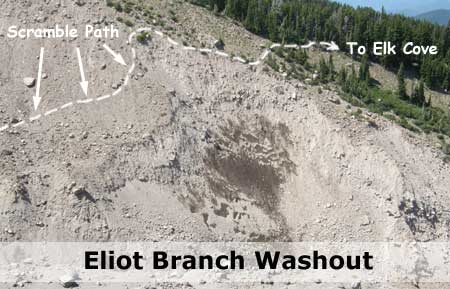

The Laurance Lake Trail was built sometime in the early 1990s and originally envisioned as a mountain bike loop. However, a landslide destroyed the old logging spur that was intended to complete the loop. Later, that part of the planned route was incorporated into the Mount Hood Wilderness, and bicycle travel is now prohibited there.

The orphaned stub of the Laurance Lake Trail remains popular for the views of the lake (below) from the open talus slope the trail traverses and the easy uphill grade that was originally built for bikes.

Laurance Lake and Mount Hood from the Laurance Lake Trail

Beyond the talus slopes the trail reaches a ridgetop that eventually extends west to Owl Point. An upper trailhead exists here, too, making construction of the connector trail convenient for crews, since work on the new trail would begin here.

Upper trailhead for the Laurance Lake Trail

Hikers have worn a path along the first quarter mile of the proposed route to and opening along the valley rim (below), with a sweeping view of the mountain.

Upper Laurance Lake Trail viewpoint

From the upper trailhead and viewpoint, the new connector would travel through a gently sloped forest for about a mile, then emerge where the unmaintained section of the Old Vista Ridge trail begins. From here, a series of expansive views into the Mount Hood Wilderness unfold along the way to Owl Point.

One of the many views along the unmaintained section of the Old Vista Ridge Trail (photo: Janice Abbagliato Messervier)

There is no timeline for this work, and federal planning processes are slow, but I’m hopeful that this new route and others that TKO has proposed can happen sooner than later. It’s no secret why people are increasingly seeking time out on trails in our public lands – the many messages in the Owl Point Log are testament to that – and there’s a tremendous backlog in meeting that need. I’m looking forward to working with TKO to be part of making it happen.

The annual TKO event at Owl Point in 2024

[click here for a large version]

Thanks for indulging me this far in a rather sprawling article and a trip down memory lane! As always, I appreciate folks stopping by and especially for being a friend of WyEast.

Hope to see you on the trail, sometime!

______________

Tom Kloster | August 2024