Verdant green was returning to the savannah meadows east of Catherine Creek in early December, just four months after the Burdoin Fire had swept through.

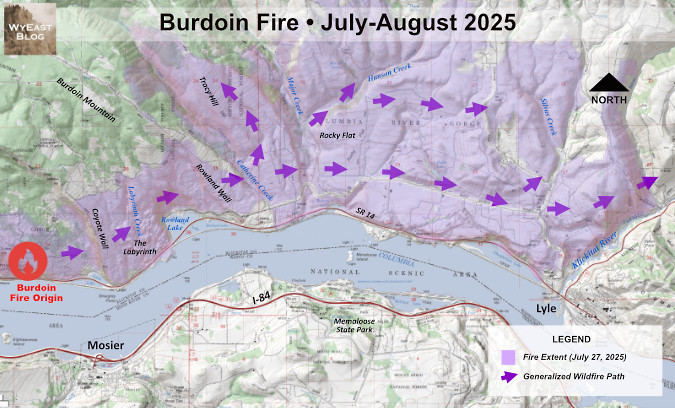

Last July the Burdoin Fire burned a swath nearly 10 miles long and blackened more than 11,000 acres along Washington State Route 14 between the towns of White Salmon and Lyle. Though no lives were reported lost, more than 100 structures were destroyed in the fire and the town of Lyle evacuated.

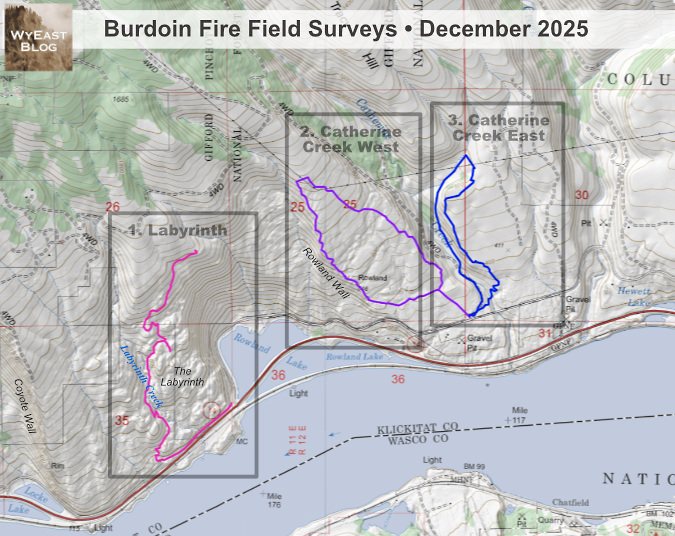

This is the final article in a 3-part virtual tour of the ecological aftermath of the fire in three separate areas with the burn zone, each with a different story to tell. Part 1 of the series can be found here and Part 2 is here. This final installment examines the eastern part of the fire, where it burned through the Catherine Creek canyon and across the sloping oak savannah directly east of the canyon (shown as subarea 3, below). This tour follows the lop shown in blue.

[click here for a large version of the map]

If the story of the twice-burned area west Catherine Creek was one of fragility – of an ecosystem not able to fully recover from back-to-back wildfires — the story of the east Catherine Creek area is a more hopeful one, where periodic fires improve the Oak savannah landscape when the ecosystem has time to rebound.

Catherine Creek East: the potential for sustainability

The third subarea in this series is the most-visited part of the Catherine Creek natural area, featuring some of the most travelled trails in the Columbia River Gorge – including an accessible loop trail and the popular Catherine Creek loop that passes a rare basalt rock arch, a unique and culturally significant place for area tribes.

The rail fence surrounding the Catherine Creek Arch completely burned in the fire, but had already been replaced by early fall to continue protecting this culturally significant spot.

An early takeaway is that Burdoin Fire was beneficial to this part of the burn, clearing overgrown brush and downed fuel and rejuvenating the sprawling meadows. Not surprisingly, the newly burned areas here fared better than those in the twice-burned west Catherine Creek area, especially the survival of oak and pine groves.

At east Catherine Creek, most of the Ponderosa pine survived, though some old giants were toppled. We won’t know the full impact on Oregon white oak trees until they leaf out in spring, though many here seem to have survived. As keystone species, the recovery of pine and oak groves here is essential to the ecosystem, and so far, the prospects for this area are encouraging.

In a pattern seen throughout the burn, deeply blackened spots mark areas where underbrush and accumulated debris burned hottest, impacting nearby trees and slowing the rebound of savannah grasses and wildflowers.

The popular Catherine Creek Loop trail begins along the stream, climbing through its vertical-walled canyon to views of the rock arch along the east wall. The trail then doubles back to follow the east rim and return to the trailhead on State Route 14. Like the Labyrinth, Bitterroot and Rowland Wall trails to the west, the Catherine Creek Loop passes mostly through a landscape scoured by ice age floods, with thin, rocky soils and craggy basalt outcrops.

Oak and pine groves grow dense and tall within the sheltered confines of the Catherine Creek canyon, but are widely scattered and mostly stunted in the exposed savannah, where the soils are thin and west winds are relentless.

The Oaks

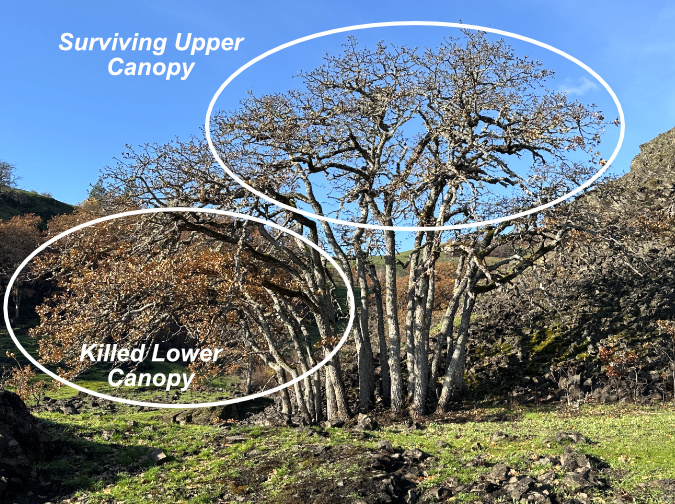

Most of the Oregon white oak groves at east Catherine Creek are concentrated within the creek canyon, itself. Here, they form large stands up to 60 feet tall, thanks to the protective 100-foot cliff walls that enclose the canyon. Smaller oak groves grow in pockets throughout the area where soils are deep enough to support them.

Tall oak groves cover much of the sheltered valley floor along Catherine Creek. Many seem to have survived the Burdoin Fire.

The canyon groves seem to have largely survived the fire, having completed their fall dormancy cycle by dropping their foliage, and thus leafless (as they should be) when I toured the area in December. This could reflect their proximity to Catherine Creek and simply being better hydrated at the time of the fire last July than trees growing in the rocky, exposed slopes above the canyon.

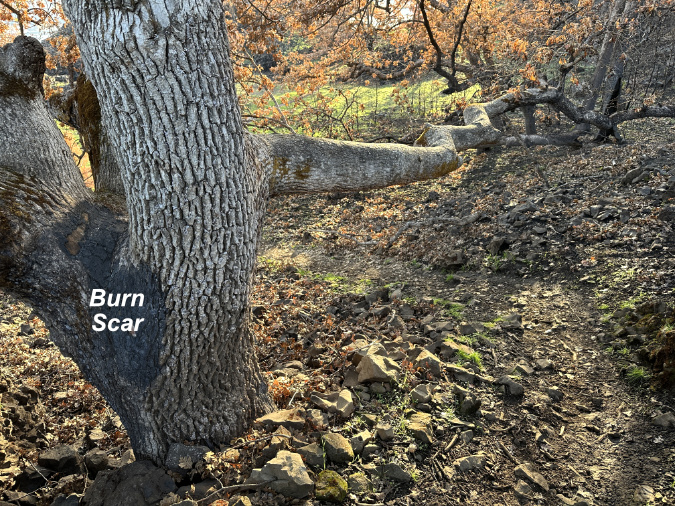

A few groves were more heavily impacted, notably the grove in front of the Catherine Creek Arch, which grows on a dry, rocky slope slightly above the canyon floor. Wherever it burned in the canyon, the fire cleared much of the understory and fallen trees and limbs that had accumulated over many years. As is the case throughout the Burdoin Fire, the canyon oaks that did succumb to the fire were often trees with hollows that allowed the fire to ignite dead heartwood, causing these trees to eventually collapse under their own weight.

A common sight throughout the Burdoin burn, this hollow oak continued to burn from the inside out long after the fire had moved east, eventually toppling under its own weight.

This ancient oak had suffered a direct lightning sometime in its long life, but was hanging on with a single limb as of last spring…

…but the Burdoin Fire quickly made its way into the old tree’s hollow trunk, burning it from the inside out….

…and leaving its fallen trunk nearby on the ground – charred only on in the inside, a common sight after wildfires on the oak savannah.

The baked ground tells the story, here – the fire burned away brush and charred this fallen log, hot enough to kill several nearby oaks.

Hollows like these can be seen through east Catherine Creek area, marking dead stump that were completely burned away by the fire – including tunnels that mark where roots once were.

This big oak at west Catherine Creek seems to have survived, if only barely….

…a closer look shows a patch of ground where the fire burned long an hot, likely fueled by brush and downed debris…

…and burning long enough to char the exposed heartwood of this tree, though not enough to ignite it….

…thus allowing the oak to complete the growing season this fall and produce another crop of acorns that will serve as a food source over the winter for wildlife and help renew burned areas in spring.

The Pines

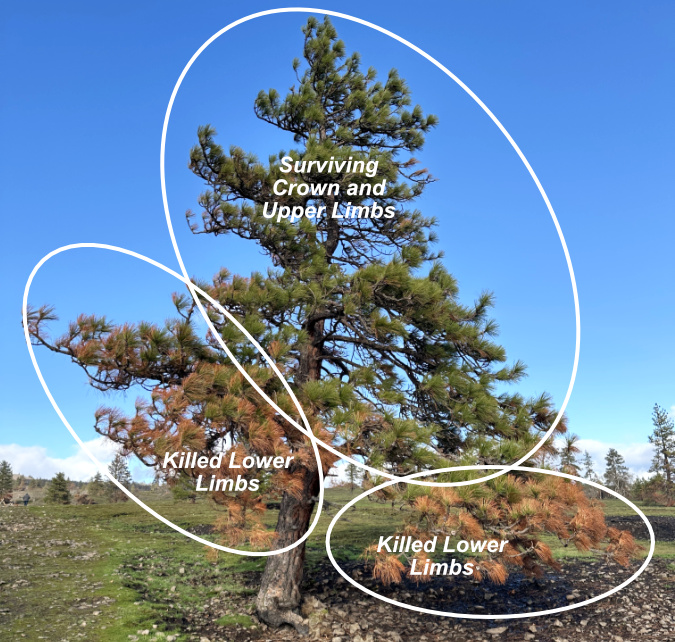

Ponderosa pine fared better in the east Catherine Creek area than in any areas to the west, including the Labyrinth, as the Burdoin Fire seems to have lost some intensity as it moved past Catherine Creek. Many younger Ponderosas in the open savannah area above the canyon benefited from the fire, as they will eventually shed scorched, lower limbs that would expose them to crown fires in future burns. Many large pines escaped the fire completely intact, thanks to their already elevated crowns that were high enough to escape the reach of the flames in this section of the fire.

As with old oaks, a few large Ponderosa were felled by the fire when prior damage to their trunk exposed vulnerable heartwood to prolonged burning. Like the fallen oaks that burned from the inside out, these big pines collapsed under their own weight once their trunks had been compromised by the fire.

This very large Ponderosa in the open savannah was felled by the fire…

…it’s hollowed out stump tells the story: the fire entered the tree’s heartwood, burning it from the inside out until the tree collapsed under its own weight.

This picturesque old Ponderosa was standing tall last spring…

…but the fire burned it almost completely after toppling the tree…

…leaving only its dismembered limbs and a stripe of bare ground where the completely burned trunk once lay…

…nearby, the hollowed-out stump was only a thin shell of fire-resistant bark still standing where the trunk of this tree once stood.

This Ponderosa is the picture of fire-forest adaptation. I’s lower limbs were killed by burning understory, but its crown remains green and healthy. If given a chance to recover for a few years, it will be even more resilient to subsequent wildfires.

This stunted Ponderosa in the open savannah is a surprising survivor, given its low canopy and nearby and numerous nearby pines that did not survive…

…but a closer look at its trunk shows that the fire simply didn’t burn long or hot enough here to char the bark, and instead only singed a few lower limbs. The blackened area east (and downwind) of the tree did burn hot, but with flames blowing in that direction, and away from the tree, it was not enough to kill this survivor.

Charred human history at Catherine Creek…

Before the Burdoin Fire, the Catherine Creek Loop trail featured an old corral and collapsed barn from when the area was still a working cattle ranch. The fire completely consumed these traces of cultural history, save for piles of rocks that once supported fence posts.

The fire also consumed wood rail fences constructed by the Forest Service several years ago to limit access to the Catherine Creek Arch, a sacred site to area tribes. While these were completely consumed by the fire, they have since been replaced by the Forest Service, just months after the fire. The new rails were even salvaged from a recent Douglas fir removal effort in the Major Creek basin, where the Forest Service is working to restore Oregon white oak groves threatened by invading conifers. The rock arch was unaffected, though several large pine and oak trees near the arch appear lost to the fire.

The old corral along Catherine Creek in better days last spring…

…and the same spot after the fire, where only the rocks that held up the fence posts survived.

New fences have already been constructed to project the Catherine Creek Arch cultural site…

…and only a few scraps of charred rail remain of the old fence.

The fire burned hot in this spot below the arch, burning a brushy area and completely destroying the old fence that protected the site. The newly installed fence is shown here, standing out starkly against burned logs and scorched ground.

The loop trail once had two footbridges, a user-built upper bridge and a large lower bridge constructed by the Forest Service in 2019. The modest upper bridge was partly destroyed by falling debris, and now is partly submerged in Catherine Creek. A large debris pile just downstream now serves as the upper “bridge” until a new structure can be built – one that has long been planned by the Forest Service.

Thought tilting a bit, the large, new lower bridge over Catherine Creek seems to have survived without any impact from the fire.

Fortunately, the much larger lower bridge seems largely unaffected by the fire. Though the flames did sweep through the area – enough to clear brush along Catherine Creek just upstream from the bridge, the structure shows no signs of fire damage.

Overall, the Catherine Creek canyon and savannah grasslands to the east appear to have benefitted from the fire. Some big trees were lost, but many survived and will be better equipped to survive the next event, given time to recover. That’s what sustainability would look like here, if we were to return to a cycle of periodic grassland wildfire.

The path forward is a choice…

It’s a fact that fire is a natural and necessary part of the Oak Savannah ecosystem of the East Gorge, but we’re entering an uncharted era with climate change, decades of fire suppression and an ever-growing population living in the Gorge. Is it even possible to find sustainability?

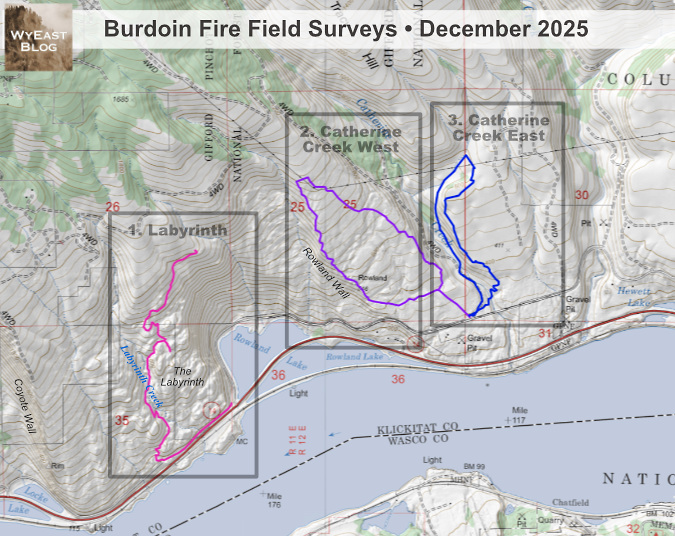

There are no easy answers to striking a sustainable balance, and the Top of the World Fire in 2025 underscored that reality. The fire escaped a controlled Forest Service burn along the upper margins of the Catherine Creek savannah, quickly spreading through the west meadows.

Social media recriminations against the Forest Service spread as quickly, with much second-guessing of the agency decision to conduct the burn, along with wildly false information about the practice, itself. If moving the public mindset away from total fire suppression was challenging before the advent social media, it has become truly daunting now.

Grassland prescribed burn in the Gorge IUSFS)

Despite the public uproar — and legitimate questions that that arose from the Top of the World incident — it’s a reality that the escalating pace of human-caused fires is a real threat to the long-term health of natural ecosystems and the safety of people who live in the Gorge. The true threat isn’t from prescribed burns, however. It’s from all of the other human activities that continue to cause the vast majority of wildfires in the Gorge. Statewide, the Keep Oregon Green non-profit puts the share of human-caused fires at 70% of all wildfires.

There is good news, however. A growing body of evidence in recent years from wildfire research continues to underscore real options for how we can slow this trend through better fire prevention and sustainable land management. Of these, prescribed burns top of the list as both essential for sustainable forest and rangeland management and for preventing or minimizing the impact of unplanned, human-caused wildfires.

Here are some key facts to consider and share as an advocate for finding balance in the Gorge ecosystem:

- Prescribed burns reduce the risk of more dangerous, uncontrollable wildfires, with studies showing they reduce fuel loads by about 50%. Consider that the Burdoin and Top of the World fires would have been much more destructive had the Forest Service not been actively conducting prescribed burns in the Catherine Creek area for many years prior.

- Prescribed burns have a very high success rate. Over 99% stay within their intended boundaries and greatly reduce the destructive intensity of future wildfires. People living on rural acreages in the Gorge can be among the most vocal in their opposition to prescribed burns because of smoke and the potential for fires to escape. In reality, controlled burns — coupled with creating defensible space on private property by clearing flammable vegetation near structures and hardening homes with fire-resistant materials – are the best defense for people who choose to live there.

- While the US Forest Service conducts roughly 4,500 prescribed fires nationally each year, only about seven (roughly 0.15%) escape, representing a tiny fraction of the over 60,000 total wildfires that occur each year – the majority of which are human-caused.

(Source for the above: U.S. Congressional Budget Office and Washington DNR))

The Burdoin Fire was only the latest of several human-caused fires occurring up and down the Gorge in just the past few years. It’s a fact that isn’t emphasized enough, with local media often reporting each event as a one-off, and rarely covering the human factor in the larger trend that is unfolding before us.

Though fire may be overdue in many of the areas that have burned, the timing of human-caused fires is usually terrible – at the height of the dry season when fires like the Burdoin burn hottest and spread uncontrollably, maximizing impacts on both the environment and people living in the Gorge.

Low-intensity prescribed burn in the Columbia Gorge in 2018 (USFS)

While controlled burns are a critical tool moving forward, they are not the sole answer. One fire prevention tool that remains largely absent is enforcement. With the infamous exception of the Eagle Creek Fire in 2017 – where teens responsible for the fire were held heavily accountable – most human-caused fires on public lands go unsolved. This deprives the public of both accountability for those causing the fire and increased awareness of the behaviors that lead to human-caused fires. The human-caused 2020 Riverside Fire in the Clackamas River canyon is just one tragic example. It remains unsolved, despite being one of the largest, most destructive fires in recent memory in WyEast Country.

Catherine Creek canyon after the fire. This is a good example of what a “sustainable” ecosystem should look like: groves of Oregon white oak, punctuated with a few spikes of Ponderosa pine.

Yet aother piece of the puzzle is shutting down access to public lands during times of extreme fire danger. Had the Eagle Creek Trail been closed on that Labor Day Weekend in 2017, when the wildfire risk was extreme, that fire would have been prevented. After the fact, the Forest Service was widely blamed for not making that call, but just imagine the public outcry if the agency had made that call, closing down recreation in the Gorge for the busiest weekend of the year – and no fires had occurred!

The same predicament isn’t new, and dogs all government agencies involved in public health and safety. While an ounce of prevention may be worth a pound of cure, public opinion and the resulting political fallout favor quick cures over short time frames of days and weeks, not preventative measures that requires months or years.

The east Catherine Creek savannah will be more open, as roughly a third of the Ponderosa pine across this grassland succumbed to the fire. The survivors will be better equipped for the next burn, moving the ecosystem back toward a few widely-scattered pines across the savannah.

Given this reality, the public health model might provide the best path for restoring ecosystem health on our public lands. That means building a broad understanding of the benefits of natural wildfires and controlled burns, and how these are different from human-caused fires.

Following the public health model would require a level of public investment in education that goes beyond Smokey Bear ads. That’s a tall order in the current political climate, but given the Federal Government has spent at least $3 billion fighting forest fires annually in recent years, there is funding to be had if this case can be made.

This gnarled old oak grows in a patch of savannah eat of Catherine Creek that dodged the fire…

…and when I went to take a closer look at this tree, I discovered that someone’s geocache was spared, too. Had the fire burned through here, the box would have survived, but the accumulated debris at the base of this tree might have burned long enough to fatally wound it.

My optimistic view is that today’s escalating pace of human-caused fires and their impact on people’s lives in the Gorge has created an opening for a more sustainable, science-informed path — despite the din of social media and our regressive politics of the moment.

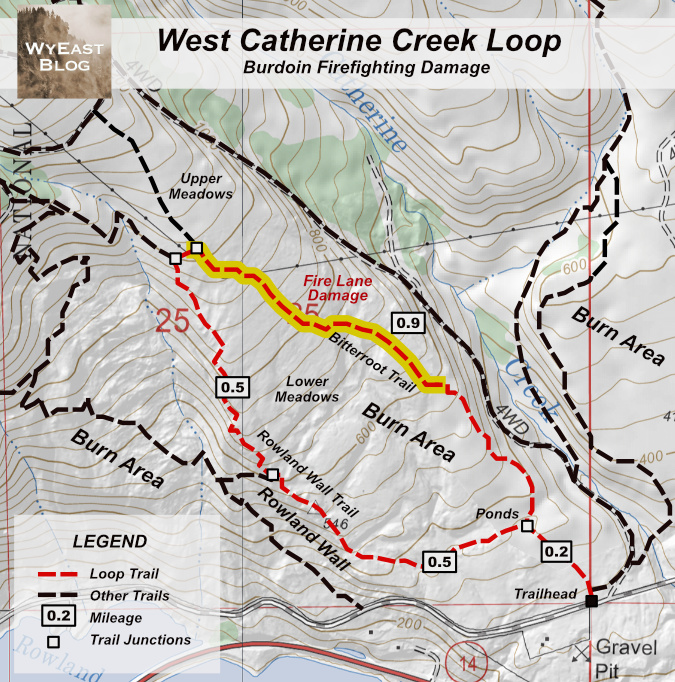

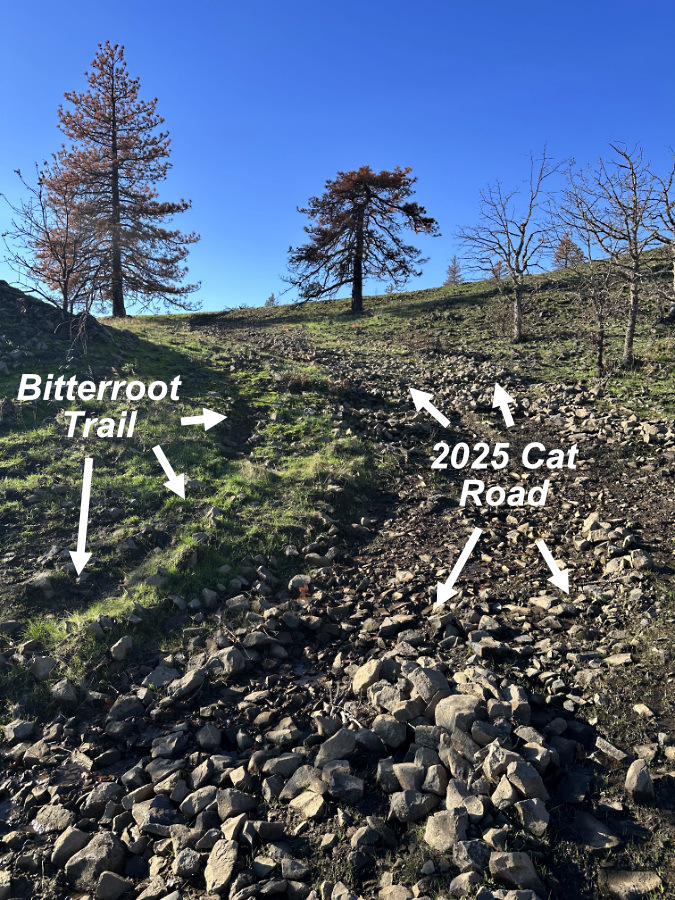

In the last installment to this series, I included this image of two hikers and their dog suddenly stopping after a rough stumble down a badly damaged trail to take in the scene before them.

Hikers (and their dog) pausing to take in the spectacular view from the Bitterroot Trail just west of Catherine Creek.

The image has stayed with me in writing this series on the Burdoin Fire. It’s just one of hundreds I took that day, yet it captures what it means to so many of us to spend time in the Gorge. I do believe that our collective appreciation of its unique beauty and vulnerability is the key to protecting this place in perpetuity, so that future generations might share the same experience. I’m optimistic that we’ll forge a sustainable path.

And a closing note…

Finally, I will also add that our “collective appreciation” for the Gorge should include federal lands workers tasked with somehow protecting this area at a time when their mission and jobs are under direct attack from the current administration. Several have reached out to me over the past year, helping me to better understand and appreciate their work. Much of it is unseen by the public, but has already made the Gorge more resilient and better prepared for an uncertain future.

While we may not always agree with their decisions, it’s important in this moment to acknowledge their work and dedication under the most hostile circumstances our federal lands agencies have ever faced. In the end, our public lands depend most on the success of those who have dedicated themselves to public service – and upon the rest of us advocate for the policies and resources they need for success.

_____________

On the Bitterroot Trail in December…

If you’ve read this far, thanks for taking the time for this 3-part series — I know it was long!! In upcoming articles I’ll be taking a close look at Mount Hood’s ever-challenging glacial stream crossings along the Timberline Trail, and I’ve got many more articles that have long been in the queue. Now that I’m retired, I finally have a moment to write them!

Thanks for following the blog! I hope to see you on the trail sometime!

_____________

Tom Kloster | March 2026

(Postscript: have you visited the new companion WyEast Images Blog? Be sure to subscribe while you’re there!)