Fireweed frames Umbrella Falls on the East Fork Hood River

Somewhere in the long history of botanical naming slander was committed, as the common name “Fireweed” was given to one of the most beautiful and useful plants found in our forests – and around the world. Thus, the noble Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium) comes to be associated with notoriously invasive plants like Horseweed, Bindweed, Chickweed, Tumbleweed and Pigweed!

But Fireweed is anything but a weed, at least by the most common definitions:

weed (wēd) noun

A plant considered undesirable, unattractive, or troublesome, especially one that grows where it is not wanted and often grows or spreads fast or takes the place of desired plants.

To the contrary, Fireweed is a widespread native in northern latitudes, growing from sea level to timberline in a remarkable range of habitats. The common name is half-right, as Fireweed is among the first and most prolific plants to return to burned areas, performing an essential role in stabilizing soil and providing shade for other flora to gradually return. Fireweed is equally at home in moist meadows, forest margins and wherever the ground has been disturbed by human or natural activity.

Fireweed has carpeted the 2011 Dollar Fire on the north slopes of Mount Hood

The string of fires over the past decade on the east and north slopes of Mount Hood have brought a sea of brilliant Fireweed blossoms to the mountain each summer. Fireweed spreads readily by seed, but are hardy perennials, so they provide years of soil stabilization once established in burned forests or disturbed areas.

Fireweed blossoms are spectacular: their spikes can grow as tall as six feet, though typically they are 3-4 feet in height. Their flowering plumes can have 50 or more blossoms, opening first at the base of the spike and progressing through their long blooming season, typically from June to September.

Fireweed flower spike

Each Fireweed blossom has four petals that alternate with four narrow sepals, surrounding white stamen and a pistil that splits in fourths.

Depending on your eyes, the blossoms are anything from hot pink to bright fuchsia. The flower stems are often bright crimson, as well, adding to the striking appearance of these plants during their bloom season.

Fireweed flower spike

The leaves on Fireweed long, narrow strips, radiating from the stem like steps on a ladder. Their leaves give the Fireweed its Latin name of “angustifolium” (meaning narrow-leaved). A close look at the leaves reveals an unusual feature: circular veins looping back to the leaf stem instead of terminating at the edges like most plants.

Given their adaptability to the wide range of habitats we have in Oregon, it’s not surprising that Fireweed is found across much of North America, as well as northern Europe:

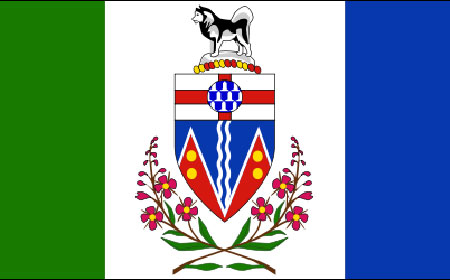

Fireweed is especially common in the boreal snow forests of Alaska and Canada, where the provincial flag of the Yukon Territory incorporates the Fireweed blossom:

While Fireweed has an important ecological role as a pioneer species in burned areas, it was also collected by native peoples in the Northwest for a variety of human uses. Its leaves were brewed to make tea, and nutrient-rich spring shoots were collected as edible greens. Even the fluffy silk from its seed pods were used for weaving.

Today, Fireweed honey and other products from its nectar are still made where the flower is in abundance in places like Alaska, Canada and Northern Europe.

Fireweed Life Cycle

Young Fireweed patch in a recently burned area

Fireweed is a perennial species with the spirit of an annual. While it springs to life from hardy roots and stems each spring, Fireweed grows as easily from its abundant seeds as any annual species, and thus its ability to quickly colonize burned or disturbed areas.

Young plants often produce one large flower spike and a couple of small spikes from auxiliary buds along the main stem. The young Fireweed shown in the photo above are typical, with young plants growing in a dense patch, each producing one main flower spike.

As Fireweed plants continue to grow over successive seasons, they form multiple branches, each with one or more large flower spike. In this way, a single mature plant is eventually capable of producing dozens of spikes. The image below shows a larger, mature Fireweed with several large flower clusters growing from the main plant.

Mature Fireweed with multiple stems

Just as the blossoms of Fireweed open progressively beginning from the base of the flower spikes toward, older blossoms soon produce elongated pink seed capsules (below) even as the tip of the flower spike is still producing blossoms.

Within each capsule, seeds are attached to a fluff of silk that acts as a tiny parachute to carry them far and wide when the capsule splits open. This is the secret to the Fireweed’s remarkable ability to colonize.

A single Fireweed plant can produce 300 to 400 seeds per capsule and as many as 80,000 seeds per plant that will float as far as the wind will take them. Seeds can persist in the soil for years and survive fire, further helping the plant function as a pioneer species in burned areas.

Fireweed seed capsules opening to reveal silk seed parachutes (USDA)

Fireweed seedlings quickly grow to form their first flower spike and produce seeds by their second year, while also establishing rhizomes that allow mature plants to spread and form clumps.

The first seedlings in a burn often take root where fire debris provides protection and mulch, with new plants quickly filling in the gaps in the first years after a fire. First year Fireweed seedlings look like this:

First year Fireweed seedlings

This two-year old seedling is coming into its prime in a still scorched area of the Dollar Fire burn, along the Vista Ridge trail:

Second-year Fireweed with a main flower spike and several auxiliary spikes

This more mature Fireweed plant has begun to spread its rhizomes and form a clump as it sends up multiple flower spikes in a protected spot by a fallen tree:

Mature Fireweed

Adding to their colorful display, Fireweed leaves often turn to blazing shades of red and crimson in autumn, another showy feature of this remarkable plant:

Fireweed foliage in autumn shades of red (USDA)

At higher elevations, the perennial stems of Fireweed are flattened by winter snowpack, but can survive the winter cold to produce broader clumps when new growth emerges in the next growing season.

What’s in a name?

With all of its beauty, versatility and ecological function, why isn’t the Fireweed more celebrated – outside of the Yukon Territory, that is?

Oh, be some other name! What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet…”

(Juliet Capulet, upon seeing her first Fireweed..?)

One reason might be its humble name, so one option would be to revert to the British name of “Rosebay Willowherb”, a common name with origins in its herbal use dating to the late 1500s.

Fireweed frames Mount Hood from Waucoma Ridge

But in the spirit of bucking norms and traditions, how another option that could be a more complimentary, modern version of it’s weedy current name? Like Fireroot? Or Fireflower? How about Fireleaf? Nope… doesn’t quite work.

How about… Firestar! Hmm… this minor adjustment would honor its essential role in stabilizing burned forests, but with a positive spin – after all, it is a “star” in this role! What do you think?

Yes, it would be a really big lift. A quick web search reveals an aerospace company, energy crystals, software brand, sci-fi novel, rolling fire doors and… a mutant Marvel Comics superheroine! If all of the above are anything like the Yukon Territory, they’d be honored to share their corporate namesake with a beautiful wildflower, right?

Where to see Fire…. star!

Fireweed crowds the Vista Ridge trail as it passes through the Dollar Fire burn

I’m not really sure how to go about establishing a new common name for a flower, but since many have multiple common names, it must be possible. So, why not try?

In that spirit, here are a couple of trails where you can enjoy magnificent displays of Firestar on the slopes of Mount Hood from mid-July into September:

Elk Cove Trail: this moderately steep trail travels through the heart of the 2011 Dollar Fire, passing near the origin of the fire just below the Coe Overlook and lots of Firestar. The overlook makes a good stopping point for those looking for a shorter hike, though Elk Cove is always a lovely place to spend an afternoon.

Vista Ridge to Eden Park & Cairn Basin: this moderately graded trail hikes through the western expanse of the 2011 Dollar Fire, passing fields of Firestar along the way before looping through idyllic Eden Park and Cairn Basin. Be prepared for a couple crossings of Ladd Creek, a glacial stream that fluctuates with summer melt on hot afternoons.

Enjoy!

One of my favorite flowers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes a favorite wild flower of mine too, Firestar sounds like a great new name, let’s go with that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Where could one find seeds to grow some of these beautiful plants?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here you go: https://www.amazon.com/Outsidepride-Flower-Seed-Fireweed-Seeds/dp/B00DIJK7WQ

LikeLike

Thanks Tom! Always enjoy your blog. Oregon has so many beautiful native plants- Firestar is amongst my favorite! I actually just recommended it to my sister to plant in her brand new backyard. That link you shared might just come in handy.

LikeLiked by 1 person